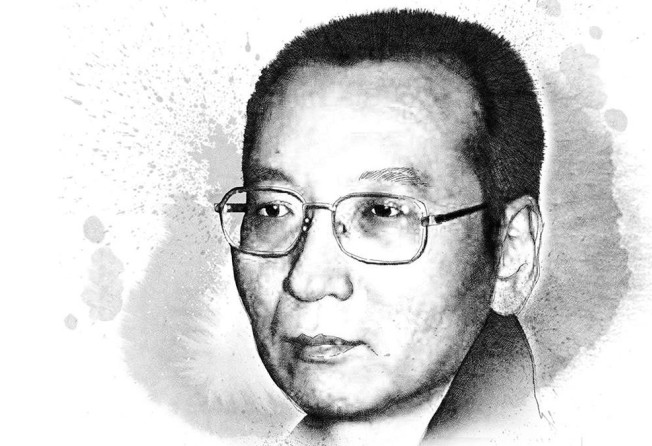

Liu Xiaobo – the quiet, determined teller of China’s inconvenient truths

Dissident won Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 for ‘long and non-violent struggle’ for human rights

Mild-mannered, cultured, gently spoken – even timid – Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo’s public persona belied his stubborn resilience and steadfastness of belief.

It was Liu’s determination and bravery to sacrifice himself for his beliefs that caught the attention of the five-member Norwegian Nobel Peace Prize Committee when it awarded him the prestigious prize in 2010 “for his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China”.

Liu, the first Chinese citizen to be awarded a Nobel Prize of any kind while still living in China, died on Thursday of multiple organ failure after battling liver cancer. He was diagnosed in May, and treated at a hospital in the northeastern city of Shenyang. He was 61. He is survived by his wife Liu Xia, ex-wife Tao Li and son Liu Tao.

Sentenced to 11 years in prison in December 2009 for “inciting subversion of state power” by co-authoring the Charter 08 pro-democracy manifesto, which called for the Communist Party to uphold the commitments made in its own constitution and that of the state, Liu was granted medical parole on June 26 this year.

Zhou Fengsuo, a student leader in the 1989 Tiananmen pro-democracy protests, was living in exile in the United States in 2008. He recalls a brief telephone conversation with Liu – which was to be their last – shortly before Liu’s arrest in December of that year, when the dissident was collecting signatures for Charter 08.

“I said to him ‘it’s remarkable that you stick to your ideas even in Beijing’, and he said ‘that’s just something I ought to do’,” Zhou recalled.

“He had the special ability to be a bridge between people with very different views ... lots of people who signed the charter were personal friends of Liu. He could connect very different people, and I think that’s what the government hates him most for.”

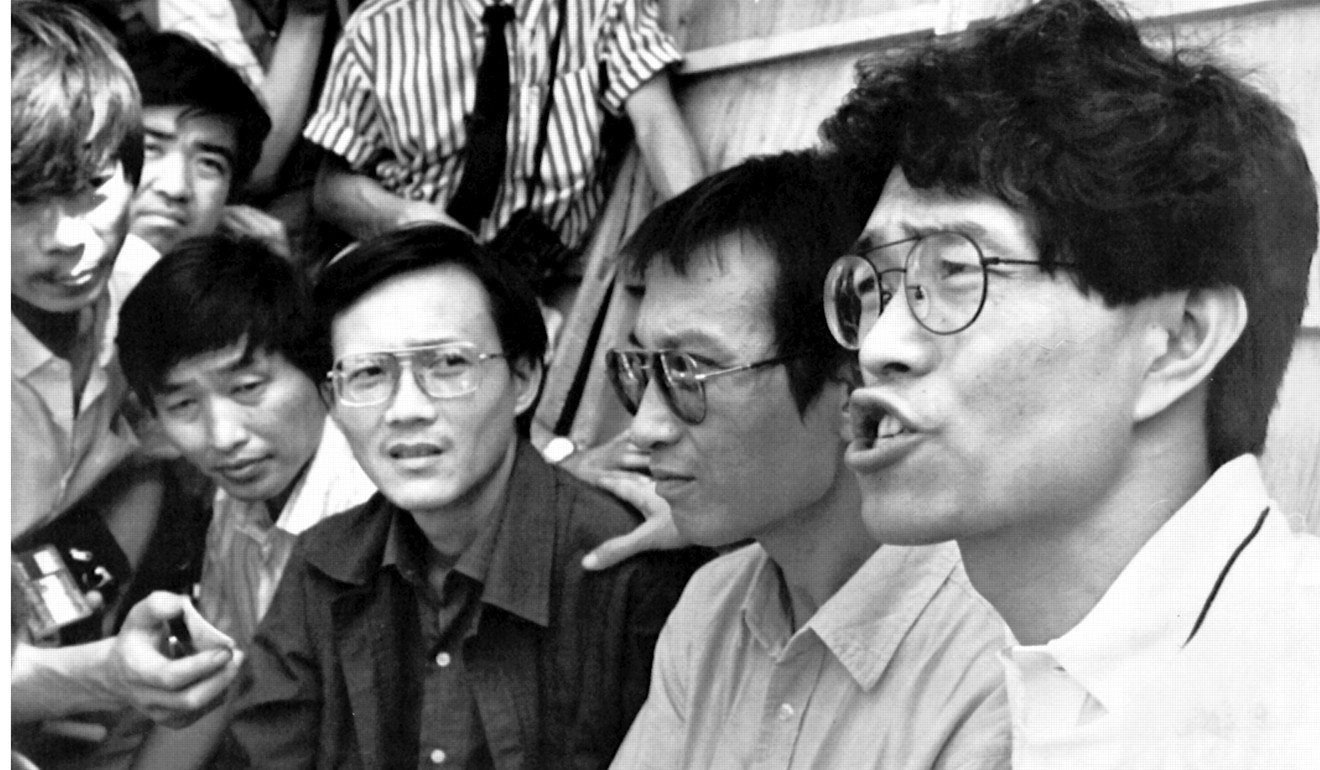

Liu first spent time behind bars in the wake of the June 4 military crackdown on the student-led pro-democracy movement in 1989. He organised a hunger strike by four intellectuals in support of the students at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square and also negotiated with the student leaders and the military commander to allow students to leave the square in peace on the morning of June 4 as People’s Liberation Army soldiers and tanks moved in. His efforts might have saved many students’ lives, but he was arrested on June 5 and spent 19 months in Qincheng Prison for his role in the movement.

Liu Suli, a former professor at the Chinese University of Political Science and Law who was jailed in the same prison after the crackdown, said Liu Xiaobo had played a major role in disarming the protesters, persuading the students to hand in all their weapons, including guns, clubs and bricks.

“He smashed a machine gun seized from the army at the square, right in front me,” he said, adding that Liu Xiaobo also delivered lengthy speeches in a vain attempt to calm the restive students.

“If the protesters had not been disarmed, I don’t know how many could have left the square alive,” Liu Suli said.

A close friend of Liu who requested anonymity said Liu became more focused on political writing after being jailed in 1989.

“He transformed from a professor inside the system to a totally independent writer,” the friend said. “He even abandoned his playboy lifestyle.”

Friends described Liu as “critical but realistic and sober-minded”, and many remembered him criticising some Chinese lawyers at a 2007 seminar forbeing too idealistic.

“Some of you write a defence script like it’s a political declaration, you can’t possibly win any case in that way,” Liu said.

Liu was equally straightforward in private. Independent journalist and pro-democracy activist Gao Yu recalled a restaurant meal they shared with a Hong Kong guest in the early 2000s. As Gao, well aware the Hongkonger would cover the bill, carefully ordered dishes and calculated their prices, Liu, at the other end of the table, yelled: “Get the crabs! Get the crabs!”

Liu Suli, who argued with Liu Xiaobo over Charter 08, said the Nobel laureate was “like a gangster when he debated”.

“He even had the haircut of a gangster,” he said. “But privately, he’s not that aggressive.”

Liu Xiaobo was thrown into a labour camp for three years in 1995 for criticising China’s one-party system and calling for political reform. It was there that he married Liu Xia in 1996.

For more than two decades, Liu fought for a more open and democratic China, most notably demanding the communist regime comply with Article 35 of the Chinese constitution,which says the country’s citizens should enjoy “freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration”.

In October 2010, while serving his sentence at Jinzhou Prison in northeastern China, Liu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, with a vacant seat on the stage in Oslo highlighting his absence from the ceremony.

Liu’s statement from his 2009 trial, titled “I Have No Enemies: My Final Statement”, was read at the award ceremony.

“Hatred can rot away at a person’s intelligence and conscience,” it read. “Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress towards freedom and democracy.”

In a lengthy article published in the South China Morning Post in February 2010, Liu rejected the 2009 court verdict, saying it violated China’s constitution and the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. “The accusations against me infringe my basic rights as a Chinese citizen and are against the basic law of China,” he said. “It is a typical case of ‘the crime of speaking’.”

The Human Rights in China NGO said that when Liu Xia told her husband he had won the Nobel Peace Prize, he said “this is for the lost souls of June 4” and then wept.

Liu’s closest friends say his devotion to pushing for democracy in China led him to stay in the country despite all his suffering.

“Liu felt deeply attached to China. He even had a martyrdom complex,” said Beijing Film Academy professor Hao Jian, a close friend since the 1990s. “He was offered the chance to go abroad several times, but he always refused.”

When he sensed he was in trouble, Liu shied away from overseas visits so he would not be banned from re-entering China, Hao said.

Beijing has sent a number of political activists to Western countries for medical treatment, but, eager to undermine the domestic influence of dissidents, it has allowed very few to return to the mainland.

“Martyrdom was not his personal choice,” Zhou said. “He was just bearing the responsibility of a survivor from 1989. That took him to a road that very much resembles that of a traditional martyr, defending his beliefs even at the expense of his life.”

Zhou said Liu’s biggest contribution was being a good example of how an individual could fight against a repressive regime and how far one could go by doing that.

“It’s like the typical image of the generation of activists who experienced 1989, one man against the tanks,” he said. “I think that kind of encouragement is what’s needed in China.”

Hours before Liu Xiaobo’s arrest on December 8, 2008, he had a heated argument with Liu Suli.

“We had a huge fight,” Liu Suli said. “He couldn’t convince me to sign Charter 08. And I couldn’t convince him to change it.

“‘Why don’t you draft a new document?’ he yelled at me.”

A close friend of Liu Xiaobo and a firm supporter of constitutional democracy, Liu Suli never signed Charter 08.

“I don’t think Xiaobo had a plan of the charter’s minimum goal, its maximum goal or what further actions could be taken following the charter ... he’s strong on heroism but he’s no good as a politician, he doesn’t seem to calculate the loss and gain,” Liu Suli said.

He said he also disagreed with Liu Xiaobo’s “I Have No Enemies” statement.

“I don’t agree that I have no enemies,” Liu Suli said. “One big question to answer in the world of politics is who your enemies are ... you can negotiate with them, work with them, but they are your enemies.”

Liu Xiaobo was born on December 28, 1955, into an intellectual family in Changchun, in the northeastern province of Jilin. In 1969, during the Down to the Countryside Movement, his father took him to a farm in Inner Mongolia. After he finished middle school in 1974, he was sent to the countryside to work on a farm in Jilin.

In 1977, Liu enrolled in Jilin University’s department of Chinese literature as part of the first batch of Chinese students to gain admission to tertiary education after the resumption of the national entry examination, which had been scrapped by Mao Zedong during the Cultural Revolution. In 1984, he earned a master of arts degree in literature at Beijing Normal University and started working as a lecturer at the university. That year he also married Tao Li, with whom he had a son in 1985.

Liu first gained fame in the world of literature as a maverick willing to challenge the status quo.

“My first impression was, he’s not a political activist, he’s no more than a literature lover,” Hao said. “When we hung out, we mostly talked about novels, literature and movies. We liked to talk about Swedish movies, mostly works by Ingmar Bergman, and books by Milan Kundera.”

Liu became well known for his unsparingly critical views of established scholars in traditional Chinese culture in the 1980s, and his strong support for Western values. His writing inspired a generation of Chinese students, including Zhou.

“During the 1980s, I was influenced by him more than by anyone else. His literature reviews were critical and deafening,” said Zhou, then a student at Beijing’s Tsinghua University. “How he upheld individual freedom was unprecedented, and was completely different from the way individuals were defined by groups and the country.”

Liu received his PhD in literature in 1988 and conducted research as a visiting scholar at universities in Europe and the US, before returning home as the 1989 pro-democracy movement broke out.

The author of several acclaimed academic books and best-sellers, Liu helped found the Chinese PEN Centre, a literary and human rights organisation, and served as president of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre from 2003 to 2007. Liu’s activism also received international recognition, with Reporters Without Borders awarding him the Fondation de France Prize as a defender of press freedom in 2004.

Writer and friend Wu Wei, who writes under the pen name Ye Du and who served as Liu’s assistant at the Independent Chinese Pen Centre from 2005 to 2008, said Liu would be best remembered for his “inclusiveness”.

“In the course of the past 30 years, fighting for freedom, his tolerance towards people, incidents and things has had a huge influence on his friends,” Wu said, adding that Liu was also passionate about nurturing young talent.

Liu’s 2010 Nobel Peace Prize made headlines around the world but the Chinese government blocked all news about it because it served as international condemnation of the communist regime’s human rights abuses and its suppression of individual liberty. A survey taken shortly after the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded found that 85 per cent of China’s university students said they knew nothing about Liu or Charter 08.

David Shambaugh, a leading sinologist at George Washington University in the US, described Liu as a serious literary critic, writer, philosopher, deep thinker and intellectual.

“He was a deeply brave man, who, like Nelson Mandela, placed his principles, his cause, and his vision for his nation above all else – and he paid dearly for it,” Shambaugh said.

Kerry Brown, a professor of Chinese politics and director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College, London, said Liu was the “most consistent, persistent and trenchant voice for political dissent in China from the period after 1989”.

Liu was known for his pro-West and pro-US stance. In an article published in 1996 titled: “Lessons from the Cold War”, he argued that “the free world, led by the US, fought almost all regimes that trampled on human rights”.

In an interview, he argued that “modernisation means wholesale Westernisation, choosing a human life is choosing the Western way of life. The difference between the Western and Chinese governing system is humane versus inhumane, there’s no middle ground.”

But he also exhibited his patriotism, saying “my tendency to idealise Western civilisation arises from my nationalistic desire to use the West in order to reform”.

Shambaugh said he placed Liu in the tradition of intellectuals dating back to the May 4 Movement of 1919.

“These intellectuals all understood the basic connection between freedom of thought and inquiry, political liberalism, science and modernity,” Shambaugh said.

Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London, said the quiet dignity, courage and renewed commitment to rights, human dignity and democracy Liu and his family showed after the intensification of pressure on them following the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize had vindicated the prize committee’s decision.

“In his death, as in his life, Liu reinforced the value of the Nobel Prize and should make his compatriots proud,” he said.

Andrew Mertha, a professor of Chinese politics at Cornell University in the US, said Liu’s relentless drive to uncover “inconvenient truths” and his fearlessness in challenging the state apparatus laid bare the official “socialist man” construct as an empty but useful fiction designed to maintain state power devoid of accountability.

“A China full of Liu Xiaobos would be ungovernable; a China without any Liu Xiaobos would be unbearable,” Mertha said.

Analysts said Liu’s political legacy would have a long-lasting impact on China’s future political development by being a source of inspiration for others striving for human rights, freedom and democracy.

“Instead of feeling sad about all that Liu Xiaobo suffered, all Chinese should be inspired by his legacy,” Shambaugh said.

Brown said Liu’s life was laden with symbolism. His demise might be read as the death of hope for present-day political reform, or as the death of the Communist Party’s moral right to continue its privileged position in Chinese society.

Tsang said Liu would almost certainly be given an honoured place in a future history of China written by the People’s Republic’s successor as the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Peace Prize and for having to pay for that honour by being jailed until his premature death.

“As Liu knew only too well, the party’s monopoly of historical narrative and ‘the truth’ cannot outlast its own political longevity,” Tsang said.