What to expect from Xi Jinping’s Communist Party congress power play

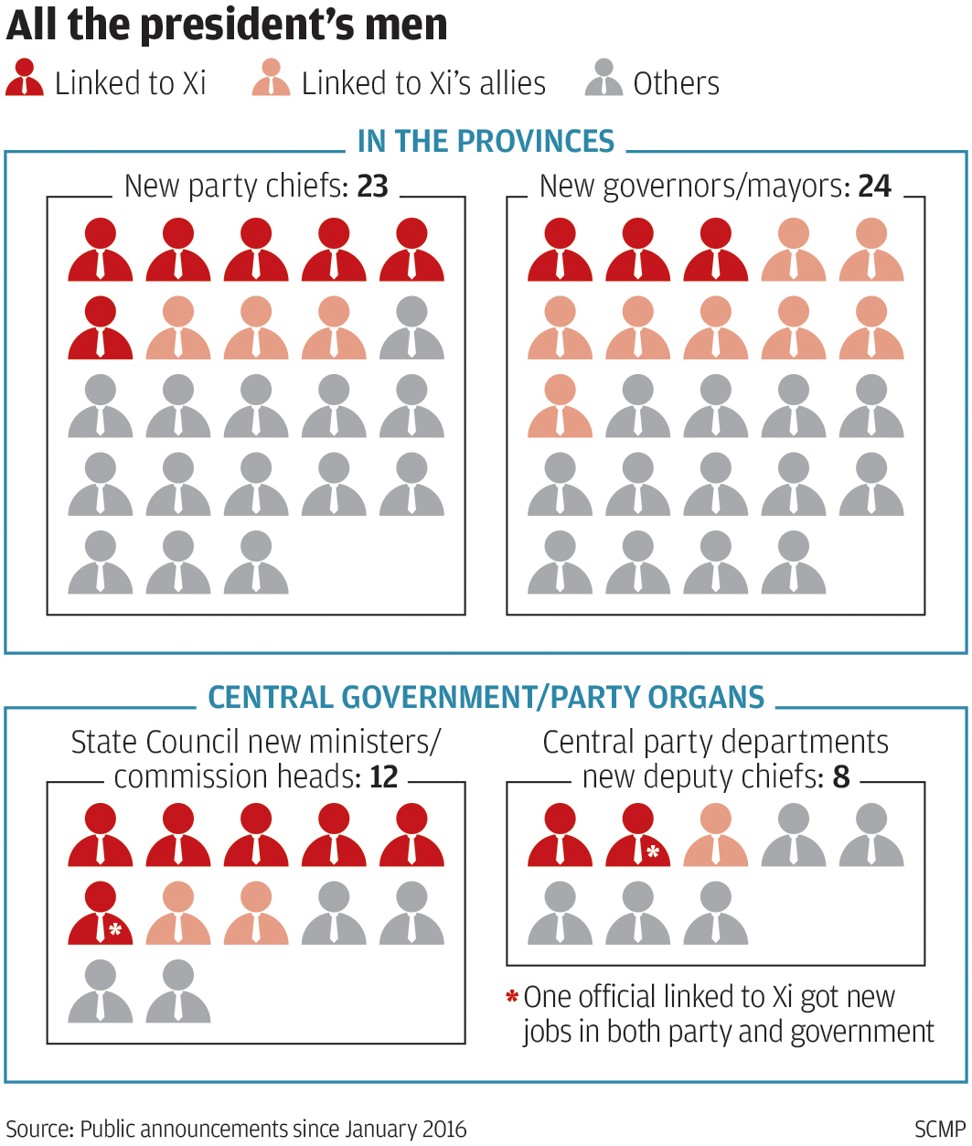

Officials linked to Xi Jinping and his allies have won promotion to key positions

When Xi Jinping took the helm of China’s ruling Communist Party in late 2012 he had few trusted allies by his side or loyal aides at his command.

The party’s Central Committee – its senior leadership – was stuffed with cadres handpicked by the previous leadership or the one before that, with many members occupying important jobs in the party and the government.

Five years on, with another leadership shake-up just months away, that situation is set to change.

Through rounds of reshuffles and a relentless war on corruption that has felled more than 200 senior officials, Xi has managed to place loyalists or associates of close allies in key positions in central and provincial government and powerful party departments. Many are now poised to be elevated to the Central Committee and some to the Politburo.

“The upcoming 19th party congress will see an all-out rise of Xi’s men,” said Chen Daoyin, an associate professor at Shanghai University of Political Science and Law. “The anti-corruption campaign has offered him many vacant positions to plant his trusted followers, in addition to the vacancies left by retiring officials.”

The latest to fall was Sun Zhengcai, once considered a possible next-generation leader, who was replaced by Xi protégé Chen Miner as party chief of Chongqing last month. Sun is under investigation by the party’s graft watchdog, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), for “serious violations of party discipline”, a euphemism for corruption and is likely to lose his Politburo seat. When he does, Chen Miner, who worked under Xi in Zhejiang, is well-positioned to take it.

Since the start of last year, eight ministries and four organisations directly under the State Council, China’s cabinet, have been given new chiefs, while the CCDI and four departments directly under the Central Committee received at least one new deputy head.

At the local level, 23 of mainland China’s 31 provincial-level regions have new party chiefs and 24 have new governors or mayors.

Most of the 67 positions are likely to come with tickets to Central Committee membership.

Of those promoted, 15 had worked with Xi during his time in Fujian, Zhejiang, Shanghai or the Central Party School, while another 14 had worked for his close allies.

The two with the highest profiles are Chen Miner and long-time Xi aide Cai Qi, who was promoted to Beijing party secretary in May, just seven months after being named the capital’s mayor. Cai worked under Xi for nearly 17 years, since his time in Fujian. Both are almost certain to join the Politburo, given the high offices they now hold, and some analysts say Chen Miner even has a shot at making it onto the Politburo Standing Committee, the party’s innermost decision-making body.

Other cadres who previously worked under Xi have now taken up leadership positions in provinces across China, including financial hub Shanghai, eastern economic powerhouse Jiangsu, coal-rich Shanxi, the central provinces of Jiangxi and Hunan, Yunnan in the southwest and the southern island of Hainan.

Provincial leadership experience is highly valued within the party and is a common stepping stone to central party leadership. Cheng Li, director of the John L. Thornton China Centre at the Brookings Institution, reckons 76 per cent of the current Politburo’s 25 members have served as provincial chiefs.

Xi followed a similar path and led three provinces before heading to Beijing as the country’s leader-in-waiting in 2007.

Professor Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute in London, said Xi’s increasing control of key provincial level leadership positions could help in the implementation of reform policies.

Many economic reforms rolled out by Xi’s administration have met with reluctance or even resistance at the local level, where officials and interest groups strove to defend their own interests.

“Xi is power hungry but not just for the sake of it,” Tsang said. “He intends to leave his mark and thus deliver real changes, but he cannot do so just by winning control at the party central or the central government level. To get his reforms, whatever they may be, implemented, he will need supporters in place in the provinces, particularly the key ones.”

Apart from the provinces, the president’s men were also promoted to key cabinet posts overseeing the economy, commerce, the judiciary, education and the internet.

In a reshuffle in late February, He Lifeng, a protégé of Xi during his time in Fujian from the mid-1980s to early 2000s, was appointed director of China’s top economic planner, the National Development and Reform Commission. Analysts said that by promoting a close associate to head the agency, Xi would further tighten his grip on economic policy, traditionally an area handled by the premier.

In the same reshuffle, Zhong Shan, who worked under Xi in Zhejiang in the mid-2000s, was appointed minister of commerce. A month earlier, Xi’s long-time speech writer, Li Shulei, became a deputy secretary of the CCDI.

Fourteen other promoted officials had career paths that crossed with those of five long-time Xi allies: top graft-buster Wang Qishan, chief of staff Li Zhanshu, party Central Organisation Department chief Zhao Leji and deputy chief Chen Xi, and Liu He, Xi’s chief economic adviser.

Tsang said that like his predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin, Xi was aiming to put enough allies and protégés in the right places to ensure he had maximum support during his second term as party chief.

But unlike Hu and Jiang, who had factional backing when they ascended to power, Xi was unable to develop his own team when he became heir apparent to Hu in 2007. Analysts said that because he could not fill all the important posts with his own men when he succeeded Hu, Xi looked to his trusted allies for supporters.

Hubei province’s new party boss, veteran banker Jiang Chaoliang, workedwith Wang in the southern economic powerhouse of Guangdong to help financial institutions cope with the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

Three other Wang associates were also promoted: Gansu party chief Lin Duo, who worked for Wang when he was Beijing mayor in the mid-2000s, and two former deputies at the CCDI, State Security Minister Chen Wenqing and Justice Minister Zhang Jun.

Chief of staff Li Zhanshu is arguably Xi’s most powerful ally after Wang and he has been a close friend the president since the early 1980s, when they were in charge of neighbouring counties in Hebei province. The new mayor of Tianjin and the new governors of Hubei and Jilin worked with Li Zhanshu when he was a provincial leader.

Anhui’s new party secretary and the new governor of Ningxia worked under party personnel chief Zhao, a Shaanxi native like Xi who widely seen as the president’s confidant, when he was governor of Qinghai and party chief of his home province.

Acting Beijing mayor Chen Jining and Shaanxi governor Hu Heping worked with Chen Xi when he was party chief of Beijing’s Tsinghua University. Chen Xi and Xi were college roommates at the university, where Chen worked for almost three decades after his graduation.

Gansu’s acting governor Tang Renjian was Liu’s colleague and later deputy at the Office of the Central Leading Group on Finance and Economic Affairs for 11 years. Liu is the president’s right-hand man when it comes to economic policy, and was described by Xi as “very important to me” during a visit to Beijing by then US national security adviser Tom Donilon in 2013.

The recent reshuffles also saw four former leaders of China’s aerospace industry promoted to head provincial governments: Ma Xingrui in Guangdong, Xu Dazhe in Hunan, Chen Qiufa in Liaoning and Zhang Qingwei in Heilongjiang.

Most of the Xi protégés promoted in the past year are not full members of the 205-strong Central Committee and some, including rising stars such as Cai, Shanghai mayor Ying Yong, Shaanxi governor Lou Yangsheng and internet tsar Xu Lin, are not even among its 171 alternate members. But many have been promoted rapidly in recent years.

Brooking’s Cheng Li said Xi’s protégés would play bigger roles in both the Central Committee and the Politburo at the party’s national congress this autumn.

“But his people cannot take all, or even more than two-thirds of the seats in these two bodies,” he said.

Tsang said that despite Xi’s attempts to promote as many of his followers as possible, he would almost certainly need to make compromises and go through intense horse-trading.

“There are a limited number of places and the rest of the establishment will not lie there and let him pack [them] with his supporters,” he said. “I doubt that Xi will himself know what he can get before the 19th congress itself. Xi is trying to consolidate as much power as he can, while some others are resisting as hard as they can against the prospect of Xi emerging as the new strongman.”

Kerry Brown, director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College, London, said identifying officials’ former associations with Xi was only scratching the surface.

“What was it about these people that caused his interest or allegiance?” he asked. “What were their policy positions, what challenges did they deal with, and were there attributes of their work that were distinctive and that we can see run across their different areas of works and different people?

“For that we need to look more closely at the political stance of these people. And there, we simply don’t have that much information at the moment. Chinese politics continues to yield its secrets grudgingly.”