Why former Chinese soldiers are sceptical about Xi Jinping’s promise of better treatment

Faced with mass protests that pose a threat to stability, Xi Jinping has pledged to set up a veterans’ affairs administration to improve their welfare

China’s ruling Communist Party, focused on ensuring stability and concerned about mass protests by military veterans, has announced plans for an administrative body similar to the US’ Department of Veteran Affairs to take better care of the country’s 57 million veterans.

However, former soldiers, accustomed to decades of disappointment and neglect, remain sceptical about the plan announced by party general secretary Xi Jinping on the first day of its national congress last month.

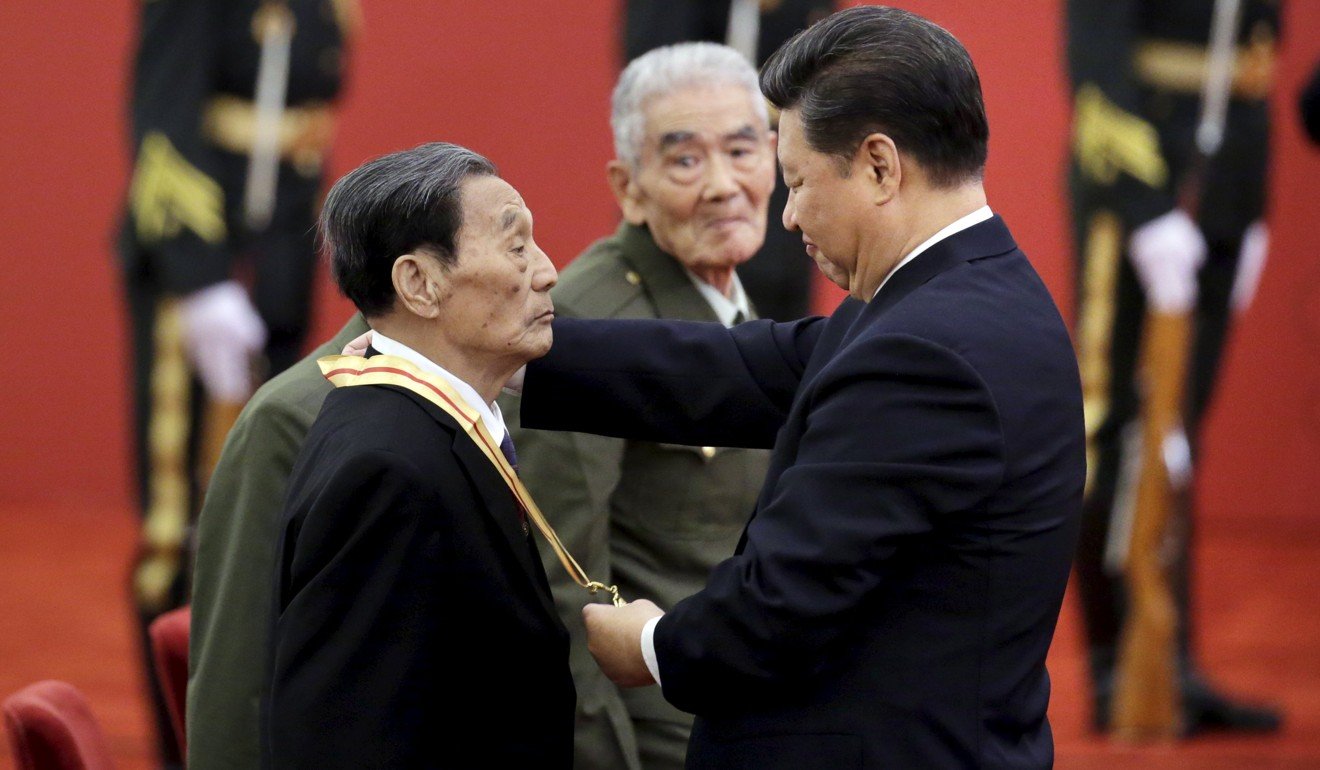

“We will protect the legitimate rights and interests of military personnel and their families, and make being a serviceman a respected profession in our country,” Xi, who is also China’s president and chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), told congress delegates in Beijing on October 18.

Thousands of veterans have taken to the streets in protest in recent years, demanding better welfare. A lack of legal protection for their rights and Beijing’s hands-off approach to their welfare has left many clinging precariously to the bottom rung of the socio-economic ladder for decades.

Xi’s promise, the first expressed so powerfully by a party chief, is consistent with his ambitious goals for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA): for it to modernise by 2035 and become a top-ranked military by 2050.

But Sun Xingan, a 61-year-old veteran who took part in the Sino-Vietnamese war in 1979, told the South China Morning Post: “It’s good news, but for us it may be just a hope, not something we would expect.

“We’ve been disappointed by our government so many times … our experience tells us to keep watching and see whether the promise will be turned into a real policy.”

A person close to the family of a late veterans’ rights activist in Yueyang, Hunan province, said many veterans had doubts about the promise, given that Beijing had stepped up efforts to “maintain stability” since Xi became party chief five years ago.

The activist, Liu Xingyao, who also fought in the Sino-Vietnamese war, was chairman of an association representing veterans of that conflict and those who served in the Korean war in the early 1950s. He was detained for 235 days in 2015 for his activism and died of a heart attack at the age of 58 a year ago.

The source said Liu’s funeral, attended by hundreds of veterans in their old military uniforms, made the Hunan authorities nervous.

“[Liu] spent his whole life, until his last breath, fighting for benefits for his comrades-in-arms and their families … but the local authorities still keep a close watch on the family after his death,” the source said. “The authorities’ nervousness would make veterans and their families more sceptical about the real motivation behind such a promise.”

In Beijing, leave for police officers and members of the paramilitary People’s Armed Police was cancelled for 22 days last month – from a fortnight before the week-long congress. A source close to the capital’s public security authorities told the Post their top mission was to prevent any protests by veterans.

“It’s a good wish from President Xi, and we veterans absolutely support him … but my experiences and gut feelings just can’t allow me to cheer up,” said Cai Wenxue, a retired air force colonel who served in the Beijing military area. “As a long-time petitioner [for veterans’ rights], I was ordered to leave my home in Beijing before the party congress kicked off. That’s why you’re reaching me on my mobile phone, because I’m now in my hometown in Shandong.”

The communist regime did not set up a veterans’ affairs administration to manage their pensions when it took power in 1949. Unlike the system in the United States, which is funded from the federal budget, Beijing resorted instead to annual orders that made local governments responsible for veterans’ pensions, medical care and other benefits.

But the documents containing those orders were not legally binding, and governments in poor areas struggled with the financial burden, resulting in recent years in an increasing number of street protests by veterans demanding dignified lives amid China’s rapid economic growth.

In March this year, just a week before the annual meeting of the National People’s Congress – China’s legislature – hundreds of veterans surrounded the Beijing headquarters of the party’s anti-corruption watchdog, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection.

That demonstration followed an even bigger one in October last year that saw thousands of veterans stage a quiet sit-in outside the capital’s August 1 Building, where the CMC has its headquarters. It was the biggest protest by veterans since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949 and the biggest protest at a sensitive location in Beijing since thousands of Falun Gong practitioners besieged the party leadership’s Zhongnanhai compound in April 1999. The central government banned the sect soon afterwards, branding it an “evil cult”.

Cai, who joined the PLA when he was just 16, was transferred to a state-owned enterprise (SOE) in his hometown, Yantai in Shandong, after he left the army in 1994. But he was laid off a few years later due to health problems and lost all his benefits. The 65-year-old veteran said that since then he had been supported by his wife, who runs a small business, and had taken on odd jobs.

Sun began petitioning in 2000 after losing his job when the Qingdao-based SOE where he worked was shut down. He now subsists on a basic living allowance of 1,700 yuan (US$255) a month.

The army mouthpiece PLA Daily has reported that China now has about 57 million veterans after at least 11 rounds of mass redundancies in what is still the world’s biggest military. The PLA had nearly 6.3 million troops in the early 1950s, making it the biggest army in the history of the world.

The latest round of cuts, announced by Xi two years ago, will see it shed another 300,000 of its 2.3 million troops.

Zeng Zhiping, a military law expert at Nanchang Institute of Technology in Jiangxi province, blamed China’s lack of an independent veterans’ affairs administration and legal protection for veterans’ rights for the frequent protests by former servicemen.

“All veterans’ benefits can only be secured if their military superiors are able to provide a lot of tedious paperwork,” Zeng, who is also a retired colonel, said. “It’s become almost impossible for a retired soldier to replace any missing document since the PLA stepped up its military modernisation and reform over the past two decades, with many departments being scrapped or restructured.”

Many retired PLA generals, including former major general Luo Yuan and former rear admiral Yin Zhuo, have proposed legislation similar to the US Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 to legally guarantee Chinese veterans’ rights and protect their interests, but with no result so far. Luo is a former delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the country’s top political consultative body, while Yin is an incumbent delegate.

“Besides legislation, it’s necessary to establish an independent department directly under the State Council, similar to the US [veterans’ affairs] department,” Zeng said.

Richard Bitzinger, a military expert at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, said veterans’ affairs had long been a knotty issue globally, even in the US, but the PLA faced a key problem – veterans’ housing – that was not something the US government had to deal with.

“The challenge facing the PLA is not simply one of a good pension and access to medical care … since most PLA soldiers live in army-provided housing their entire career … they need someone to provide that,” he said.

The US Department of Veterans’ Affairs employs nearly 240,000 people and its budget for the coming financial year is US$186 billion – bigger than China’s US$151.43 billion military budget this year. It is not clear how much the Chinese government spends on veterans’ affairs.

“In short, the PLA will have to up its support for veterans and retirees if it wants to create a Western-style modern military,” Bitzinger said, adding that would require “a professional military personnel system”.

China has a long history of neglecting former soldiers. The Song dynasty in the 10th century paid former civilian officials better pensions than retired military officers, and the Kuomintang regime that preceded the communist takeover also failed to come up with a sustainable pension system for its soldiers, including the 600,000 veterans it took to Taiwan when it lost the civil war.

In a commentary published by China Youth Daily late last month, Zhou Zhou, a researcher at the PLA’s Academy of Military Sciences, called on the central leadership to learn from Western experiences when coming up with new veterans’ affairs policies.

“Veterans are a special community in every country around the world,” he wrote. “Whether their affairs can be properly handled directly affects [a country’s] combat effectiveness, the military’s morale and the stability of the state.”