Xi Jinping is changing the constitution, but what’s his endgame?

Revisions all point to the same goal – strengthening the party’s legitimacy and institutionalising its rule by blurring the line between it and the state

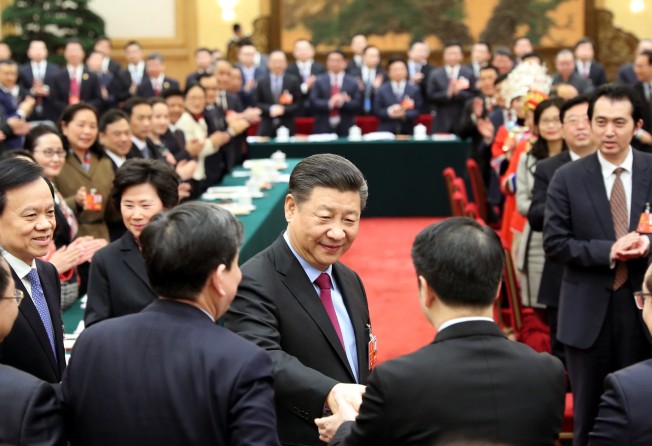

Soon after Xi Jinping took the helm of the Communist Party in 2012, he gathered China’s political elite in Beijing to mark the 30th anniversary of its modern constitution.

“No individual or organisation is above the constitution,” the new party chief thundered from the podium of the Great Hall of the People.

“Anyone who acts against the constitution or the law will be held accountable.”

Few people attached great significance to the speech at the time. After all, Xi’s predecessor Hu Jintao said something similar after becoming the party’s general secretary in 2002. Some liberals even felt encouraged by it, and hoped Xi – the son of a bold reformer – would use his authority to strengthen the constitution that promises both freedom of expression and freedom of assembly.

On Sunday, as China approves the most drastic constitutional amendments in decades, there is little doubt that Xi was deadly serious – though he has not taken the direction liberals had hoped for.

With the whole world focusing on the revision to remove the president’s term limit, it is easy to overlook the bigger goal of Xi’s move: staying in power beyond 2023, but on his own terms.

Theoretically, Xi does not need to amend the constitution to continue as leader – the role of president carries little real power and is the least important of the three titles he holds, the other two being party secretary and chairman of the Central Military Commission.

The 21 proposed changes to the constitution all point to one objective: to strengthen the legitimacy of the party and institutionalise its rule by blurring the line between party and state.

Analysts familiar with the party’s thinking said Xi believes the amendments are necessary because the challenges China faces today require not just a strong leader but also a unified and strong ruling party. These revisions will bring an end to the debate over whether the party is above the state.

Li Shuzhong, vice-president of the China University of Political Science and Law, said after the upheaval and violence of the Cultural Revolution, party elders had reflected deeply on the dynamics between the party and the state.

At first they thought the two should have a clear division of labour or even separation.

“But the result is that the party’s leadership gradually became weakened. The party’s administrative efficiency was compromised. He [Xi] believes the party organisation is losing its power and this, together with the corruption problem, is a big issue,” said Li, who was a policy adviser on the constitutional amendments.

“[Xi] believes that to reform China, we first need to reform the party. That strengthening party rule will improve the governance of the state.”

Li added that the situation during the Cultural Revolution – from 1966 to 1976 – of a total overlap between party and state must be avoided.

“We worry about the same old problems,” he said. “How exactly should the party lead all the affairs? There should be more regulation.”

A key part of the constitutional amendments is the addition to Article 1 of a description of the party’s leadership as “the most fundamental characteristic” of Chinese socialism. The reference to the party’s leading role previously appeared only in the preamble that covers China’s history and vision for the future, and which most legal scholars say is not legally binding.

That left room for some liberals to question the legitimacy of one-party rule. Before the revision, even among cadres there have been different views on this, and that division is seen as a threat that could fragment the party.

Gao Kai, a retired National People’s Congress official and party member, was one of those who questioned the constitutional foundation of one-party rule, in an article that appeared in influential liberal magazine Yanhuang Chunqiu in 2011.

“I have reviewed the constitutions of more than a hundred countries, as instructed [by the party],” wrote Gao, who was involved in drafting China’s 1982 constitution.

“Aside from a few authoritarian states, no country that claims to be democratic stipulates in its constitution that the whole nation is led by any one political party or individual.”

By making this change, Xi and the party leadership hope to dispel these lingering doubts over the constitutional legitimacy of one-party rule, according to a source familiar with discussions on the matter.

“Some say [one-party rule] is not written in the constitution and use that to question the [legitimacy] of the party’s rule,” said the person, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they are not authorised to openly discuss the matter.

“In fact, the party’s leadership is always implied in the constitution, it’s just that it is not clearly spelt out. The amendments will end that unnecessary discussion and let us refocus our energy on development.”

Xi first indicated his plan to end the debate in an internal speech in 2015, which was subsequently published in a book.

“[Arguing] whether the party is above the law or under the law is a political trap and an invalid argument,” he said. “We will not give ambiguous answers to such a question.”

Sunday’s revisions are the latest step in an ongoing effort to fuse the party with the state that has been under way since Xi took office.

Under Xi, the party has sought to assert its leadership in the state apparatus, as well as in universities, social organisations and even foreign firms.

Last year, Wang Qishan, Xi’s trusted ally who wields tremendous power and influence, said in public that “there is no such thing as separation of the party and the state”.

That was seen as a sharp departure from the idea of late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, who advocated this separation after the Cultural Revolution.

“In the past, there was a sense that the party’s role is often a hidden one, it operated somewhere more in the shadows and wasn’t so visible. Now, under Xi Jinping, its role has become very visible,” said Eva Pils, an expert in Chinese law at King’s College London.

“As we can clearly see from the constitutional change, the idea is to emphasise party control, to tout the concentration of power as a virtue of the anti-liberal system.”

Spelling out the party’s role in the constitution will provide a legally binding foundation to ensure its leadership, according to Qin Qianhong, a law professor at Wuhan University.

“It was only in the preamble before, and most scholars consider it a non-binding directive,” Qin said. “It will be legally binding now, after it’s put into the body text.”

Taisu Zhang, a law professor at Yale University, said the party’s emphasis on the constitution would ultimately increase the political costs of breaching it.

“Using the law as a political tool has the long-term consequence of deepening its sociopolitical salience and legitimacy,” he said. “As soon as [Xi] continues to use it as a political tool, he will find that it becomes more socially entrenched, and therefore that the political costs of violating it increase.”

Pils said the revision to the charter completely changed the concept of the rule of law, and made it a tool that the Communist Party could apply at will.

“That is a completely anti-liberal concept of the rule of law,” she said. “It is the idea that the law can be used as and when needed, but also that it can be suspended as when needed by the party.”

Qin said the revision may cause tension and confusion, given the constitution’s limited protection of civil rights.

“People will ask if the party’s leadership is the first principle of the Chinese constitution – and how this principle will affect the other principles such as ensuring the equality of individuals and the protection of human rights. There will be some kind of tension,” he said.

Qin expected to see the expression of party leadership appear in other laws as well.

The debate over the party and the state is a long-standing one. Deng initiated the move for “separation between the party and the state” to limit the party’s role in the state’s daily operations after the Cultural Revolution.

It was part of an effort to tackle excessive concentration of power, seen by the party as the root of the political mayhem during the Mao Zedong era, though Deng had also drawn a red line on Western notions of the separation of powers. The idea of separation of the party and the state is seen by many as one of Deng’s most important political legacies.

But this has all changed under Xi, who believes that China’s problems – ranging from corruption, to bureaucratic inefficiency, to stalled market reform – are all consequences of the party’s leadership role being compromised.

Through a series of changes, culminating in the constitutional amendments and a government restructure, Xi is seeking to further cement the party’s grip on all aspects of life – something the president summed up with a phrase that is rarely heard in the post-Mao era, during his speech to the party congress in October:

“Government, military, society and academics are like the north, the south, the east and the west [equally important]. But at the centre is the party. The party leads them all.”

Additional reporting by Nectar Gan