Sun sets on China’s billionaire Taishan Club as Communist Party takes care of business

- Low-profile private society counted some of the country’s biggest entrepreneurs as members and had tough entry standards

- But group has disbanded amid party’s drive to redefine the role of businesspeople

The dissolution of a Skull and Bones-style private club of some of China’s most famous tycoons has raised concerns over what roles entrepreneurs will play in the country’s next phase of modernisation.

The Taishan Club – a private club with about 20 members – was “disbanded a while ago”, a former member told the South China Morning Post on condition of anonymity.

“[We haven’t had] gatherings for quite some time. The club’s official registration has been cancelled. It’s time to move on.”

The club’s disbanding comes as top Communist Party leaders insist that entrepreneurs be clear about the roles they play in the country’s modernisation and national rejuvenation.

Chinese leaders maintain that under the party, China has had a decisive victory over the coronavirus pandemic and is on course to becoming a “modern socialist country” by 2049.

In September, the party issued a new set of guidelines calling on the heads of private businesses to work with the party to “form the backbone of the private economy that can be relied upon and be of use at critical times”. It also said societies of businesspeople must be “guided” and “supervised”.

The Taishan Club has kept a low profile since it was founded more than two decades ago by some of mainland China’s best-known entrepreneurs, many of them from the tech world.

Named after a culturally significant mountain in eastern China, the group first registered under the name of the Taishan Industrial Research Institute in 1993.

The business empires of its members have since grown to cover almost all sectors in the Chinese economy, from technology to real estate and entertainment.

According to Chinese media reports, the exclusive club had formidable membership requirements, including annual fees in the “millions of yuan” and hefty penalties for failure to attend meetings.

As the country’s private sector grew, other clubs emerged, among them the Jiangnan Club founded by Jack Ma of Alibaba, which owns the Post. Ma was also reportedly a member of the Taishan Club many years ago.

Over the decades the Taishan Club tried to stay out of the public eye and politics but gained a reputation as a Masonic-style group.

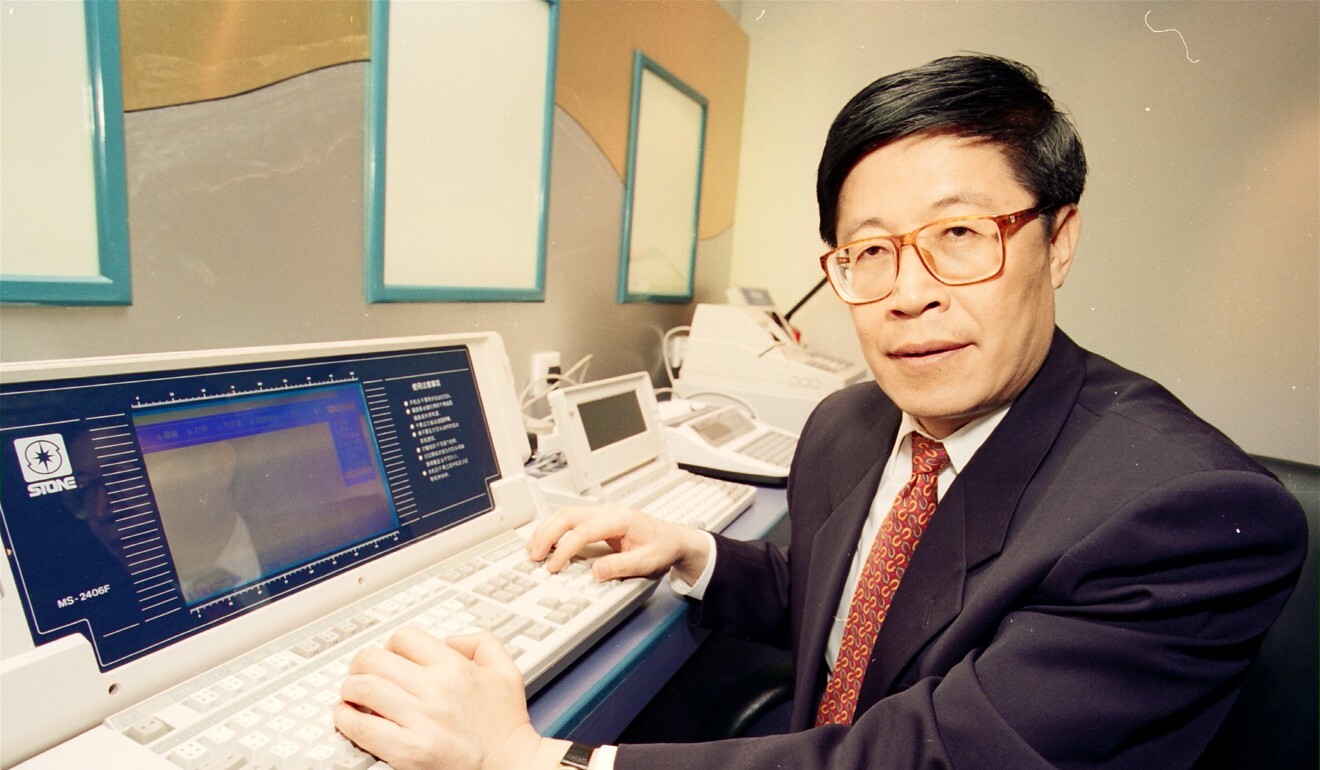

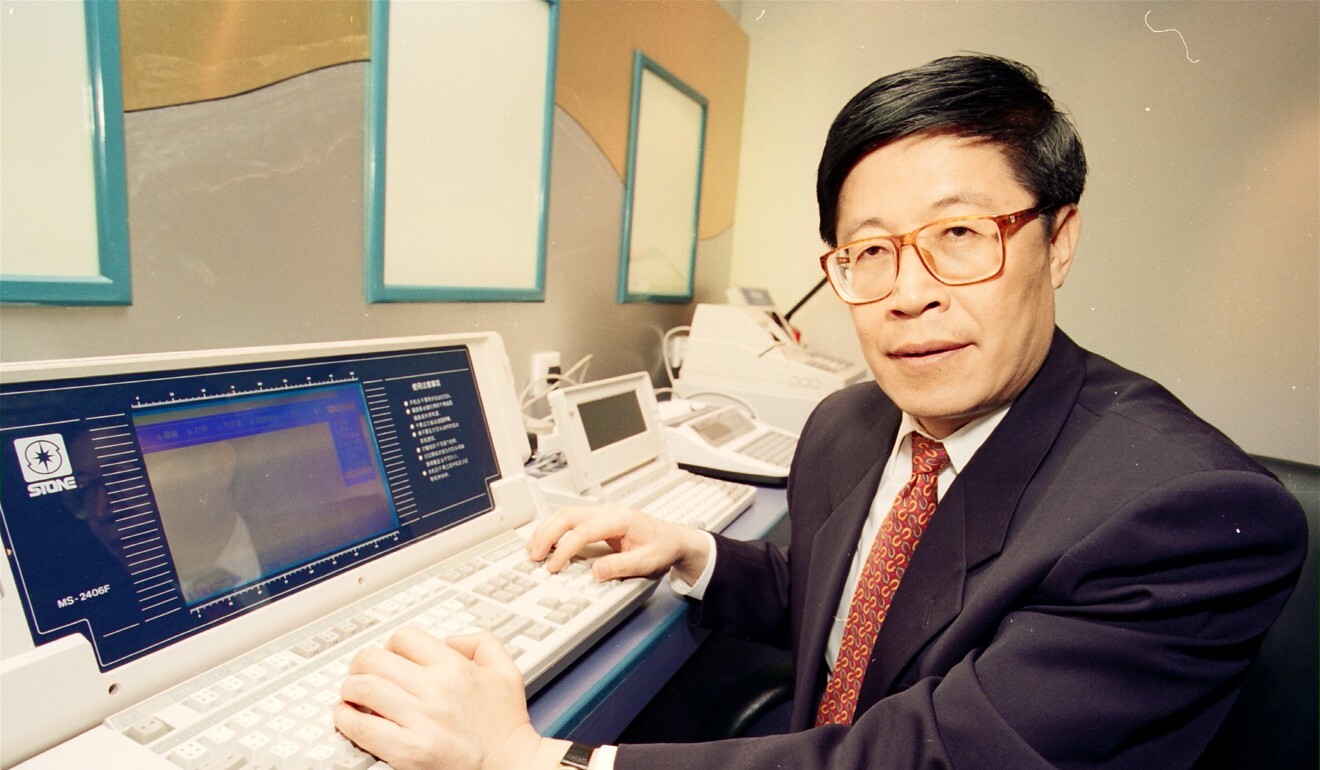

Its membership was never confirmed but bigwigs such as Lenovo founder Liu Chuanzhi, Baidu chief executive Robin Li Yanhong, Fosun Holdings’ Guo Guangchang, and Vantone Holdings’ Feng Lun were thought to be among its ranks.

In 1997, when Shi Yuzhu’s Giant group was caught in a financial crunch, fellow Taishan member Duan Yongji of the Stone Group was rumoured to have helped Shi.

BBK Electronics founder Duan Yongping said last month that he was a member of the club for two years and joined “to find people to play golf with”.

“We would have meals once or twice a year and chit chat. [On the surface], there was nothing secretive but some members were a bit mysterious,” Duan wrote on his social media account.

“There was not much point [for me] staying since everyone had his own ideas,” he wrote, adding that he had since quit. “No one played golf or maybe I wasn’t sociable [enough].”

Nevertheless, the clout of private clubs like the Taishan raised eyebrows among party leaders, according to Alfred Wu, associate professor at National University of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

“[These] tycoons can move billions of dollars [if they want],” Wu said.

About six months ago, the party issued guidelines that made it clear that such private societies must be reined in and regulated.

“Those business organisations without registration shall not engage in social activities ... Organisations that meet the requirements must be registered and managed in accordance with the law,” the party guidelines said. “[We should] strengthen the guidance and management of forums, seminars, lectures, salons and other activities held by entrepreneur-related organisations.”

Then, at a Lunar New Year gathering with non-party advisers on February 1, President Xi Jinping called on the business elite to reaffirm their commitment to the party.

Xi also instructed the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce – the party body that communicates with the private sector – “to promote the healthy development of private economy and assist the entrepreneurs”.

“[We should] strengthen political and ideological guidance [on the private economy],” state news agency Xinhua quoted Xi as saying.

Wu said China was trying balance the need for economic growth in a turbulent, post-pandemic world with a vibrant but orderly private sector.

“[Former paramount leader] Deng Xiaoping proved the vibrancy of the private economy after Mao’s total planned economy model failed. Jiang [Zemin] took a step further in welcoming entrepreneurs to join the party,” Wu said. “Now, Xi’s key concern is achieving the national rejuvenation goal, so there’s the need to define who are the good entrepreneurs.”

On trip to Jiangsu province in November, Xi held up Qing dynasty industrialist Zhang Jian as such a model for others to follow. Zhang pushed for investment in industry to strengthen the country and set up education and social welfare institutions to give back to society.

Zheng Yongnian, dean of the Advanced Institute of Global and Contemporary China Studies in Shenzhen, said China would not pursue a Western economic model of modernisation, and Chinese entrepreneurs and their conglomerates would have a different function than they would elsewhere.

Rather than simply breaking up companies China should look for ways for firms to realise their inherent social responsibility to use technology for good, he said.

“For China, we should think more about how to guide the development of these business giants,” Zheng said.