01:31

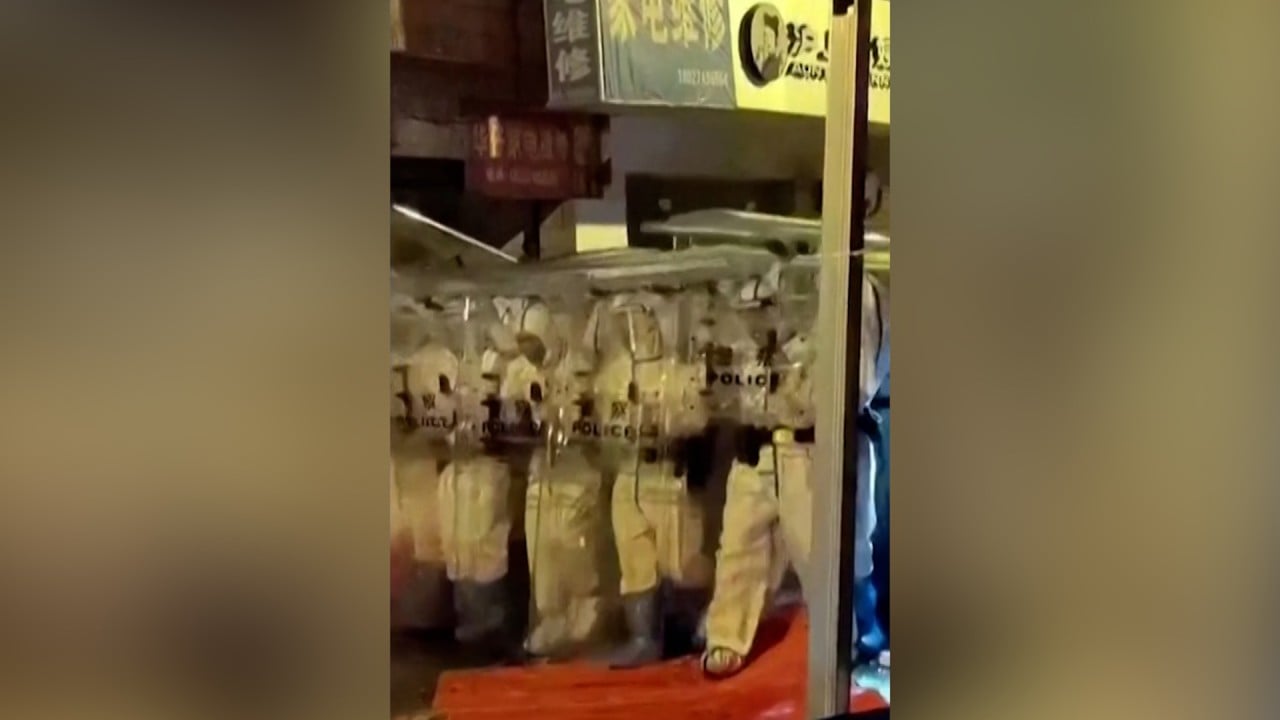

Two massive Chinese cities ease Covid-19 curbs as protests spread

While major Chinese cities have started phasing out draconian Covid-19 measures, the consequences of prolonged social isolation on mental health are unfolding in hundreds of millions of students across the nation.

In the longest school closures among major countries, mainland China’s students were made to sit in front of computers at home and listen to live or recorded lessons for their schooling, an expedient option taken by local governments seeking to prevent transmission on campuses.

Over the past three years, the duration of screen-based teaching may have varied – from weeks to months, or even semesters, depending on the frequency of local Covid-19 flare-ups – but attending online class from home is a shared experience among children and adolescents in mainland China. And various research projects have found they are paying a heavy price for the Covid-related social isolation.

Mason Wang, a first-year student at a Beijing college, spent nearly half of his three years of high school at home doing online classes, resulting in little time with his classmates.

“We call each other internet friends,” Wang said. “Now I can hardly match the faces with names of classmates.”

Isolated from his peers, he spent most of his spare time playing computer games and ended up scoring poorly in the university entrance exams.

Wang did secure a place in college but struggled to take an interest in other people and his studies because he was confined to campus for more than two months this year during the most recent local flare-ups.

“I know I should pick up the pieces, but it’s so hard. Sometimes when I wake up at midnight, it scares me to think about tomorrow. I’ll be a loser forever,” he said.

Lockdowns and school closures during the pandemic left children around the world isolated, away from their peers and unable to socialise and grow.

The mental health of the vulnerable, including children and young people, should be at the heart of countries’ health systems and key to recovery from the Covid-19 emergency, the World Health Organization said earlier this year.

In China – where mental strain is common among students amid intense competition to get into the best schools – depression, anxiety and anger became even more prevalent during the three Covid years among children and adolescents, various research reports show.

Peng Kaiping, a psychology professor at Tsinghua University, and his team surveyed 300,000 primary and middle school students around the nation last year.

“It is prevalent – the young generation, amid Covid-19 control measures, lacks motivation to study, enthusiasm to live and ability to socialise and they feel their life is purposeless,” he told a Beijing forum in May.

“The number of students in anxiety, depression or losing emotional control rose markedly [from pre-Covid years].”

The university recruited more than 3,000 volunteers for its 24-hour psychological intervention hotline. During the three years, they received 10,500 calls and dissuaded 138 people from committing suicide, according to Peng.

There were also worrying signs in a survey led by academics at Peking University. The researchers polled 8,079 students aged between 12 and 18 during lockdowns in 21 provinces in 2020 and found that 44 per cent suffered from depression, 37 per cent from anxiety and 31 per cent suffered from both.

In 2020, paediatricians at the Second Hospital of Jilin University conducted two surveys of more than 3,000 students aged between 6 and 12 in the northeastern province of Jilin.

The results showed that amid Covid-19 curbs, children living with a single parent, a big family or impatient parents were more vulnerable to mental illness than their peers.

“Covid measures obviously have an impact on students’ mental health, influencing their emotion and behaviour,” the researchers, led by Zhao Zhiruo, wrote in a paper in the Chinese Journal of Contemporary Paediatrics in June last year.

“In the arduous and enduring battle against Covid-19, their mental problems should not be overlooked,” they wrote, calling for collaboration among families, schools and society to help the students recover.

The Ministry of Education introduced psychological classes and consulting services to campuses last year to help students manage their emotions, as well as an alarm system to intervene at the earliest sign of a student having a setback or showing a negative change.

However, many parents still feel helpless because the damage of isolation has been done and yet Covid-19 curbs remain in most parts of China.

Qi Shengli, a taxi driver in Guangdong, is worried about his two children 1,500km (930 miles) away, left behind in his hometown in the central province of Henan.

He said his children had to live at their school in their county capital and could only return to their home village once every three weeks for a weekend, because of strict epidemic precaution measures.

Lately, with the spike in outbreaks nationwide, Qi’s village has banned villagers from leaving. Fearing that outsiders might bring a new Covid-19 infection, village officials have ordered all households to lock their homes or, for those that cannot be locked, to fasten the gate shut with wire, according to Qi.

He said it was becoming more difficult for his children to return to be home with their grandparents.

“I told my children to ask teachers for a mobile phone to call me when they missed me and my wife. But they just rarely called,” Qi said.

“I often miss my children, worrying if there is enough food at school, if they are being bullied or will not be happy. But in fact our communication with kids has become less and less because of the epidemic.”

Qi’s concerns echo the fears many Chinese parents have about their children’s potential psychological problems. The mental health of students has become a hot topic on social media platforms, with parents and teachers sharing their concerns about children’s addiction to the internet.

Susan Zheng, 46, a manager of a financial firm in Beijing who works from home, said her 14-year-old daughter rarely talked to her.

“She chats with her friends via WeChat for hours every day. When I try to stop her, she always gives me a cold look,” Zheng said.

“She used to be an outgoing and pleasant girl. Now she’s very aloof. If possible, she would not like to meet anyone offline, be it our relatives or even her friends. I’m really worried how she will adapt when the society reopens.”

Xu Ying, a Shenzhen-based teacher, said the city’s students had been taking online classes for months. “As a teacher, I feel that obviously they are lonely and do not know how to get along with others. They seldom talk with other people politely and seem a bit withdrawn.

“They need their parents’ love and concerns more than ever before, yet their parents are struggling to support their families, burnt out amid worries of job losses and pay cuts, and are able to offer less attention than ever for their children.”

Kathy Chen, a Guangzhou-based white-collar worker, is afraid children are drifting away and losing connection with peers who live in other countries that have already reopened.

“It’s hard for us to help kids with that. I’m so afraid that they have got more used to living in such an echo chamber because of China’s lockdowns,” Chen said.

“I am eager to protect my child’s positive and multicultural perception of the world and make her feel safe. But it was difficult to live a normal life in China in recent years, let alone resume summer camps and take part in various overseas matches.”

Bian Yufang, director of Beijing Normal University’s mental health and education institute, has advised schools and families to be prepared for the reopening of school because students could have difficulty adapting.

“Students’ mental problems could become more prominent due to a change in the pace of life and the pressure to catch up and reduce dependence on mobile gadgets,” Bian said.

If you have suicidal thoughts, or you know someone who does, help is available. For Hong Kong, dial +852 2896 0000 for The Samaritans or +852 2382 0000 for Suicide Prevention Services. In the US, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on +1 800 273 8255. For a list of other nations’ helplines, see this page.