Meet the Chinese villagers who fear they can never escape the poverty trap

- Poor rural villagers stake all on sending their children to university as sustained government campaign fails to reach their remote homes

- Many residents believe they will die poor and ‘can’t even dream’ that things will change

Sitting on the stone bed of his decades-old house in a remote village in Hebei province, Zhang Liansuo explains why he has no hope that his family will ever be able to escape poverty.

Despite the country’s ongoing campaign to eliminate poverty, the farmer explained that so far all he has received is a bottle of cooking oil, 10kg of flour “and nothing else”.

His home village of Xiaoguancheng the depth of the Taihang mountains is just three hours’ drive from Beijing. But despite the country’s decades of breakneck economic growth, it remains one of the poorest places in the country, with few jobs available and where many families still survive by subsistence farming on land too barren to grow anything but corn.

Next year, according to a deadline set by President Xi Jinping, the whole Chinese population should be lifted above the poverty line – defined as an annual income of at least 2,300 yuan (just over US$340).

But despite the campaign’s undoubted successes – the number of rural poor has fallen from 82.39 million in 2012 to 16.6 million at the end of last year, with another 10 million population set to be lifted out of poverty this year – families like Zhang’s are at risk of being left behind.

Returning to Xiaoguancheng a year after the South China Morning Post last visited, things appear to be going backwards for Zhang.

Last year he lost his 8,000 yuan a year job working as a forest ranger, instead getting seasonal work as a fire prevention officer which pays up to 400 yuan depending on the time of year.

He was also able to pick up various odd jobs that brought in around 1,500 yuan during work to build a new square in the village, but he doubts that he will be “lucky” enough to make that much this year.

Zhang and his family dress in second-hand clothing donated by a charity, which they clean in a 20-year-old washing machine, and their house’s leaking roof is in need of repair.

They sleep on traditional stone beds known as kangs, heated by a small coal-powered stove that fills the house with smoke in winter, and their sole source of entertainment is an old television that they bought second-hand 10 years ago.

For food, the family relies on corn that they grow on a small plot, less than half an acre in size, and exchange for flour or vegetable.

Their other regular source of income is a 2,000 yuan allowance for Zhang’s wife and son, both of whom suffer from mental disabilities.

“They can’t cook by themselves. I would be able to make more than 1,000 a month if I went to look for jobs in cities, but I don’t even dare to leave home to have an operation on my varicose veins because there is no one to look after them,” he said.

All his hopes are pinned on his 16-year-old daughter, known as Little Zhang, who may one day be able to go to university and get a job that could help support her family.

I don’t think I will be free from poverty before I die

“I don’t think I will be free from poverty before I die,” said her father. “My hopes are that she will go to university. We won’t settle for vocational school or getting married to help the family.”

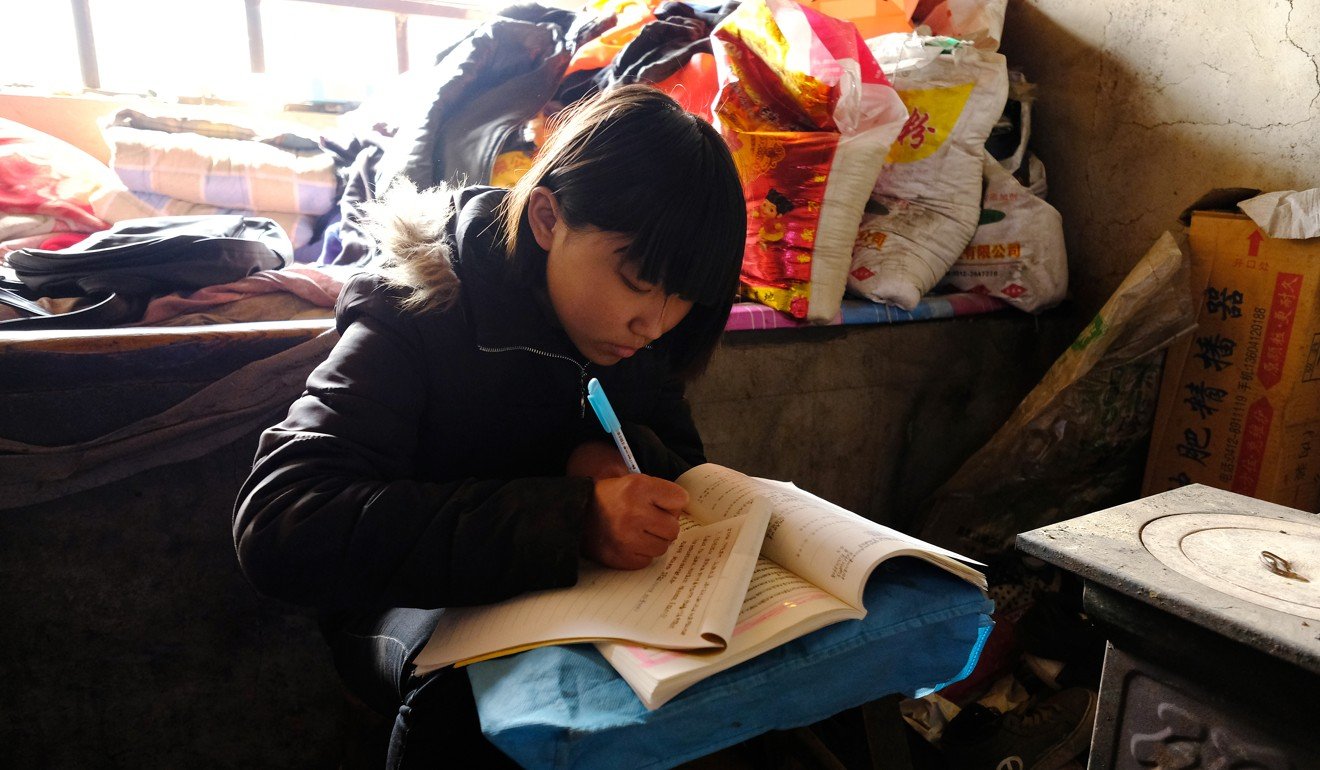

Little Zhang is in her final year of middle school, where she boards during the week, and has been working hard to secure a place the best local high school.

She is well aware of the weight of expectations and said she would continue to work hard.

“I am under a lot of pressure. We are on a 100-day countdown for the exam when I go to back school at the end of February,” said Little Zhang. “I am too worried to think about the future except that university is the only way out.”

Based on her scores in mock exams she is on course to secure a place at the high school, but she says she still needs to do better.

“My teacher said we already have one foot in the high school. Getting in is the first step and we need to work hard to get good scores. Only those who are admitted to the advanced level class will have a chance of being getting into a good university,” said Little Zhang.

She said she was interested in the Chinese language and history but was struggling with physics, chemistry and English.

She also said she needs to catch up on politics: last time she had to guess the answer when asked to name the current president of the United States, adding that only 20 per cent of her classmates knew that it was Donald Trump.

At present she studies from 5.50 in the morning to 9.20 at night, only returning home once every two weeks, and she regards her time as so precious that she even tries to recite passages from her textbooks while jogging during PE classes.

“I have my dreams, like going to a university, becoming a teacher and providing a better life for my family, but I am also well aware of the cold reality. I will need student loans and to find part-time jobs to support myself,” Little Zhang said.

The government is looking for ways to help children from poorer backgrounds get a good education.

On Tuesday Premier Li Keqiang told the country’s lawmakers that a campaign would be launched in impoverished rural areas to reduce drop-out rates and help more students from such areas to enter university.

Little Zhang herself has benefited from earlier initiatives to help students from her background to gain a place in high school and waive her school fees.

Following last year’s report in the Post, she has also benefited from the generosity of a reader who offered the family thousands of yuan to help pay for her education.

Her village at the foot of the Taihang Mountain served as an old revolutionary base during the war against the Japanese invaders due to its remoteness, and many other local families regard education as their best hope of finding a way out.

I can’t even dream that I will stop being poor

Wang Donghai, 21, a third-year student at Hebei Agricultural University in Baoding, is well aware of the pressure he is under – especially because his family has borrowed heavily to help pay his tuition fees.

The family currently lives on 2,000 yuan a year from growing corn and has started raising some chickens in the hope of selling their eggs to make a further 1,000 yuan.

His father Wang Sheming has debts of 50,000 yuan and regards his son’s future job prospects – and not the poverty reduction campaign – as his main hope of paying them off.

“Help? What help?,” he asked. “There are some cleaning jobs for 650 yuan a month in the village, but it’s a hot job and I didn’t get one.”

“I can’t even dream that I will stop being poor. I am old and I need to take care of my 92-year-old mother. All I wish for is that my son will find a job to provide for the family.”

The burden of expectation has turned the younger Wang’s university days into a challenge, at least, if not an ordeal.

“After so many years of education I am well aware that I need to find a job to support the family and improve their livelihood.

“I am struggling because the job prospects for my major, studying technology and equipment, are meagre. My teacher asked us to try further studies – but admission is highly competitive and that also means I will still need family support,” Wang said.

Wang makes some money from handing out fliers in the city at weekends, but cannot find the time to do this when exams are looming.

“Life is so hard. I have learned not to compare anything with the others. I have stopped asking myself why I was born into such a family when I see my classmates getting new computers, changing their phones or just buying new shoes.

“I know my father has expectations but I have nobody to lean on but myself,” Wang said.

“I can’t help thinking about this at night and the more I think about it the more difficult it becomes for me to fall asleep.”

Li Guoxiang, a researcher with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said that without better job opportunities it was going to be very difficult to lift families above the poverty line.

He said the poverty alleviation campaign recognised the importance of education, which he said was “vital to prevent poverty from passing down between the generations”.

“There are interest-free loans to help students but for some families it might still be very difficult,” Li said.

He said eventually the government will try to provide for families whose household income is not enough to lift them above the poverty line.

The Ministry of Civil Affairs estimates 20 million people will still need help when the current alleviation campaign ends next year, compared with the current total of 45 million recipients of low-income allowances.

The anti-poverty campaign will continue after 2020, but Li said the focus will shift from lifting families above the poverty line to reducing the wealth gap between rich and poor.