Community the silver lining for growing number of elderly Chinese living and dying alone

- Academic says nation is in ‘awkward period’ as 255 million people aged over 60 deal with economic change and legacy of one-child policy

Unmarried, alone, and without children, a 67-year-old man who lived in Shanghai’s Baoshan district died at home without being noticed by anyone until his body started to rot.

He was a private person who hadn’t been in the best of health, the Xinmin Evening News reported. Although he left his front door unlocked, his body went undiscovered in the summer heat until the end of July, when the smell prompted his neighbours to call the police.

Just a month earlier, a woman in her 70s who lived alone died in her flat in Nanjing, the Yangtse Evening Post reported in June. She had a son and a daughter who visited her every couple of weeks, but she was only found dead beside her bathtub when a community worker paid a routine visit.

The cases are just two that have made headlines in a country where older generations have traditionally lived with and been cared for by their children and grandchildren. There is no official data on how many people in China live by themselves but observers say planners will need to anticipate their needs as the population ages.

The central government forecasts that by next year China will have 255 million people aged above 60, accounting for 17.8 per cent of its total population. That’s up from 220 million four years ago.

China’s population is greying in part because people are living longer but also because the one-child policy and economic changes have led to lower fertility rates. Of those aged over 60, nearly half do not have children or live apart from them, experts say.

“Our traditional culture is that elderly people live with their children and grandchildren, and die in a big family,” said Zhu Qin, an expert on ageing from Fudan University in Shanghai.

“We’re now in an awkward period, as on the one hand, with the birth rate declining and family size reducing, the family’s role in elderly care has lessened, while on the other hand, a social security network for those people is still being built.”

One place China can look to for precedent is Japan, where more than a quarter of people are over 65.

“China does not have the worst ageing issue in the world, but its population is getting old faster than most countries,” Zhu said.

“Our study found that what China’s going through happened in Japan 30 years ago. Generally, we’re behind Japan by 30 years and it has offered meaningful experience for us.”

In Shanghai’s Yuer community, about 22 per cent of the 2,000 residents are over 60, according to the residents’ committee.

One of those older residents is 69-year-old Shen Ming, whose husband died of cancer last month.

Shen said that unlike the generations before her, when there was little choice but for older people to live with their children, today’s elderly valued their independence and would rather live separately.

“You have different habits and lifestyles,” she said. “Living with the kids often leads to conflict.”

Shen said she had two children who live in Shanghai, and they had their children to take care of and jobs to do, so they only visited her once every few weeks.

Like many older Chinese, she also does not want to live in a nursing home, but her reasons are less about lifestyle and more about pragmatism – the nearest nursing home charges more than 5,000 yuan (US$707) a month.

“Most of the elderly people I know in the neighbourhood would prefer not to go to a nursing home. It’s the same as waiting to die, they say. But I think differently,” she said. “I’d go now if the fees were not so high.”

However, places in nursing homes are few and far between. Throughout the country there were about 30,000 elderly care organisations providing 7.46 million beds last year, the National Bureau of Statistics said. This amounts to about 30 places for every 1,000 people aged over 60.

Adding to the worries is the growing number of families who have lost their only child, a number that by some estimates is already more than a million and increasing by 76,000 each year.

Li Jufen, a 66-year-old divorcee whose only son died of cancer in 2017, said her future was most probably in a nursing home.

“It would be a lie if I said I never thought of the possibility of dying alone at home,” Li said. “The good thing is that I have enough pension and savings for a nursing home in the future, and that I take care of myself well.”

Li is among the first generation of parents from China’s one-child policy era to enter retirement. The country adopted the policy in the late 1970s, restricting couples to having one child – a rule that was not eased until 2014.

Despite the policy change, China’s birth rate in recent years has remained low and last year births fell to 15.23 million, the lowest since 2014, official data showed.

Zhu said the peak of the ageing population was expected in 2030. “So the next decade will be very crucial in terms of expanding care for the elderly.”

In Shanghai, grass-roots government bodies were already checking up on older people who live alone, usually by phone or dropping by their homes regularly, residents said.

Zhu said technology was also available to help monitor the home of an elderly person.

“Those measures are directly aimed at avoiding lonely deaths,” he said. “I don’t think it’s totally negative for elderly people to live alone – it’s an inevitable stage of life. The point is, there should be support from the society and action from the government.”

Then there are networks that older people can form themselves.

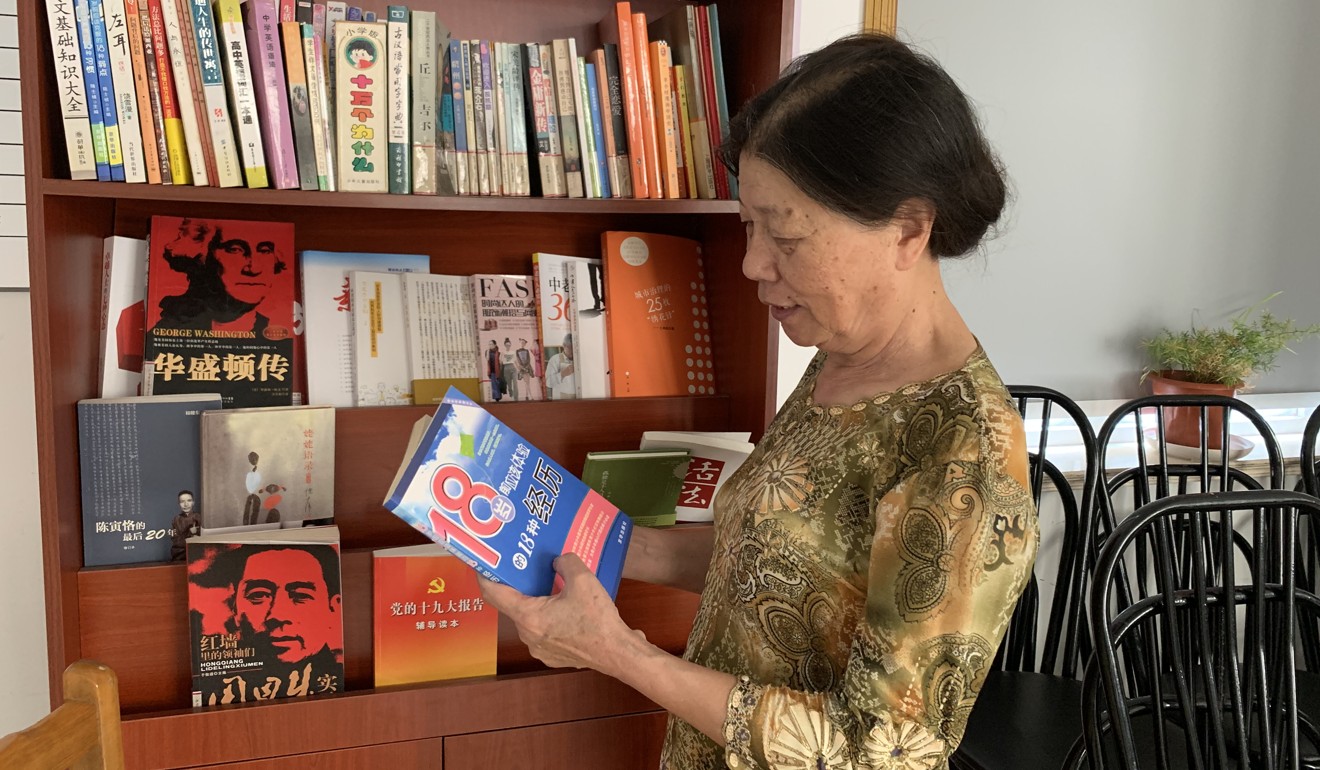

Shen, the widow, is a volunteer for the residents committee, making sure all the elderly people in the community are safe.

“The volunteer work cheers me up,” she said. “There are many others who live alone like me, and if I haven’t seen them for one or two days, I ask the neighbours if they know where they are.”