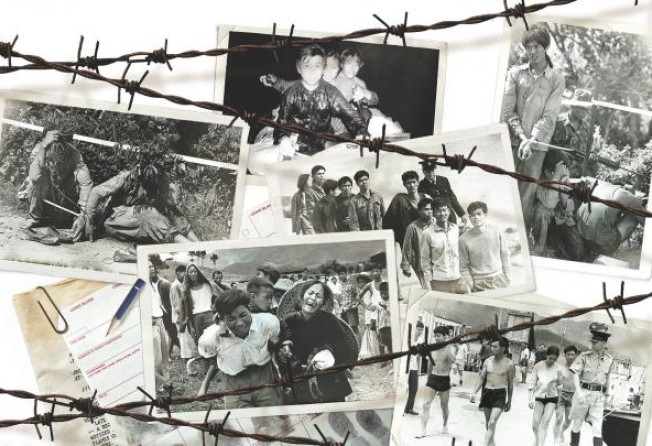

Veterans who fled mainland for Hong Kong in 1970s tell their stories

Veterans of mainland exodus in the 1970s tell how, as young men with no hope, they risked their lives to reach Hong Kong as illegal immigrants

Mok was just 26 when, despondent and demoralised, he decided he had no future on the mainland and would try to flee to Hong Kong.

Even with good marks at school, he could not get into senior high school or the army. And when he joined a state-run farm, hoping that hard labour would prove his loyalty to the Communist Party, he still found himself endlessly assaulted by fellow workers in mass "political struggle" sessions.

During the Cultural Revolution, Mok was given the job of raking out tonnes of cinders at a pesticide factory, where the toxic fumes often made him feel ill. As someone from a "black" family, he was forced to denounce himself in front of hundreds in often violent political struggle sessions that never seemed to end.

"In this vast land of 9.6 million square kilometres, there was no place for me," the 67-year-old said, remembering how he felt 41 years ago. "If I didn't run away, I'd be a despised 'dog' for the rest of my life."

Mok - who remains reluctant give his full name because he still has business interests and family on the mainland - spent months preparing for the big day when he would try to flee to Hong Kong.

Like many young men with the same idea, he put himself through a punishing regimen of exercise and swimming, gained knowledge of geography, map reading and weather forecasting and familiarised himself with edible plants.

His first attempt, in 1971, failed. After walking for days, he and his companions nearly drowned when they tried to swim towards Hong Kong and were caught by border guards. He was taken to various detention centres where he was beaten as a traitor and put on public parade before being sent back to his factory, where he was insulted and tortured at many more political struggle sessions.

That just made him even more determined to escape. He made it to Hong Kong the second time - in 1972. "Instead of being beaten to death, I'd rather risk dying in the sea in my quest for freedom," he said.

He was just one of hundreds of thousands of young people who risked their lives to escape from the mainland to Hong Kong in search of a better future in the 1960s and 1970s.

For more than 40 years, many of those who succeeded kept quiet about their horrendous experiences because the "illegal immigrant" label still carried a stigma. But in recent years, a few have begun to break their silence as they reach retirement age and want to tell their stories. Some of their memoirs were presented for the first time at a conference held at the Chinese University of Hong Kong last month. The conference, "Fate of a Generation, Fate of a Country", was initiated by Professor Michel Bonnin, a China expert at the Paris-based Ecole des hautes etudes en sciences sociales.

Reliable statistics about just how many mainlanders escaped to Hong Kong during that period are not available but Professor Ho Piu-yin, a historian at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, estimates they accounted for 20 per cent to 30 per cent of population growth between 1961 and 1981, when the number of people living in Hong Kong grew by about two million.

Wang Shuo, a Shenzhen official, wrote in the outspoken political journal Yanhuang Chunqiu in 2011 that an estimated 606,000 people illegally escaped to Hong Kong between 1956 and 1980 - more than half, 332,000, between 1970 and 1980.

Many were among the 20 million youngsters sent to rural areas to be "re-educated by peasants" in Mao Zedong's "up to the mountains and down to the countryside" campaign during the Cultural Revolution. With their city hukou - household registration - cancelled, they were unable to legally return to their hometowns and their thoughts turned to the capitalist haven of Hong Kong. Because of its proximity to the British colony, many in Guangdong were determined to risk their lives to escape.

Worried that they might be caught, many did not dare to carry maps but memorised their routes. They often hid in hillside bushes until night and hiked in the dark, surviving on wild plants and their own food - often balls of flour mixed with oil and sugar.

They scaled steep hills and winding paths and many were bitten by snakes or attacked by wild dogs or boars. Some slipped and fell to their death, while others got injured and gave themselves up for arrest.

Others spent months training in water. The lucky ones ended up in Hong Kong after swimming all night but the less fortunate drowned, were eaten by sharks or were caught by Hong Kong police and sent back to the mainland.

Many escapees recount stories of their companions being torn to pieces by sharks and disappearing into the sea. One of the more direct routes, Dapeng Bay in Shenzhen, was dubbed Shark Bay.

No matter which route they chose, many never made it. Their anxious families waited for months to receive good news from Hong Kong but never heard from them again.

But even though they knew of the high risks involved, many who failed the first time still tried again and again.

Cheung Yu-tack, a teenager from Guangzhou who was sent to Hainan Island in 1969 to work on a collective farm, only made it to Hong Kong on his fourth attempt in 1974.

On his first attempt in 1971, Cheung was caught by border guards and bitten by their guard dog. He was then locked up in detention centres for four months before being sent back to the Hainan farm, where he was badly beaten at political struggle sessions.

On one of his other attempts, Cheung reached Hong Kong waters but was sent back to the mainland by colonial police. Finally, he reached Hong Kong's Kat O (Crooked Island), narrowly escaping a police patrol after a gruelling overnight swim preceded by a 10-day hike. He left behind his girlfriend, who broke a leg. She was arrested but later escaped to Hong Kong, where they married.

New arrivals in Hong Kong such as Cheung did odd jobs, worked in factories and became part of the cheap labour force that made Hong Kong the world's factory in the 1970s.

Professor Ho said the colonial Hong Kong government, which until 1980 granted illegal migrants who evaded arrest on arrival the right to stay, realised that the extra labour could contribute to economic growth.

"Industries such as electronics and clock manufacturing needed intensive, semi-skilled labour, and these people, in their prime working age, contributed greatly towards our industrialisation," she said.

The wave of illegal emigration also prompted the mainland authorities to rethink their economic policy, scholars said. Late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, who was said to blame extreme leftist policies for the mass escape, launched the "reform and opening up" policy and endorsed the development of Shenzhen - a key hub for illegal migration - into a special economic zone in the late 1970s.

The shift towards a market economy unleashed the mainland's pent-up productivity and turned it into an economic powerhouse.

Tan Jialuo, a former lecturer at Guangzhou Teachers' College who has researched the history of the Cultural Revolution, said the escapees played an important role in that process.

"Not many circumstances have changed the Communist Party's policies, but the mass escape to Hong Kong was an exception," he said. "It had an important role in the initiation of reform.

"People resorted to escaping for the sake of survival but through risking their lives they effectively helped to promote social progress."

Wong Tung-hon, who worked in Hong Kong electronics factories for decades after his escape by boat in 1970, said: "People like us used our lives to pave the way for the reform and opening-up era." He said he was proud to have participated in creating the "Hong Kong miracle".

His eyes reddened as he recalled three childhood friends who drowned in the sea while trying to swim to Hong Kong.

Surprisingly, many of the escapees, who turned their backs on communist rule in their youth, cannot see the link between authoritarian rule and the disastrous policies that led to their lost years.

One escapee said he remained opposed to the Communist Party, but said China would "descend into chaos if not ruled with a firm grip".

Tan, who was also sent to the countryside as a teenager during Mao's campaign, said the victims of repressive policies often failed to see that the dictatorial nature of the regime was to blame for their misery.

"The 'red' education has been absorbed into their blood … and they lack the ability to reflect on things independently," he said. "Reflection is a painful process of severing what has already become part of themselves."

Some even express a hint of regret when they see friends who did not escape now enjoying state pensions and social welfare benefits they don't have in Hong Kong. But others, like Wong, say they have no regrets.

"I have a vote and they don't. I know what the jasmine revolution is and they don't," he said. "I'm proud of my experience. While we fought against the dictatorship and protested with our feet, many of them were still shouting 'long live Mao'."