Losing a baby, and then his first wife: former Hong Kong broadcaster relives harrowing WW2 memories

This is one of a series of stories in remembrance of the Battle of Hong Kong and the dark days that followed.

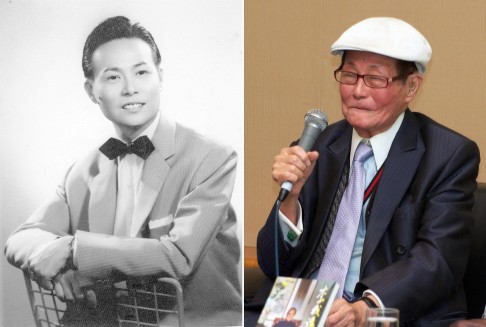

At 93, Lee Ngaw’s broadcasting voice is still crisp, rising and quivering as he recalls his days of suffering and loss during the war.

“I could have died many times over, but the good heaven has been kind to me,” the nonagenarian said with a sigh, lying in his bed and nursing the ailment of old age.

Born in Guangzhou in 1922 as Li Man-king, he moved to colonial Hong Kongat age five with his mother, a single parent who was a Chinese doctor.

“When my mother died in 1936, I was abused by my aunt who took everything my mother left me. Hence I took up the name Ngaw, which means ‘I’ because that’s all I had as a 14-year-old,” he recalled. He was then a top student at WahYan College.

“No one took pity on me except a young student from a neighbouring school. She was a year older than me and from a rich family. Gradually we fell in love, got married and had a son,” he said, fighting back tears.

When the Japanese troops attacked Hong Kong in December 1941, the young couple had just become parents again, after losing their eldest boy the year before.

“We lived in Catchick Street in Kennedy Town Praya and the Japanese charged from Aberdeen. We were very scared but had nowhere to hide except the bed we rented from the landlord,” he recalls.

Fearing for his safety, they put their toddler son into a nursery home for a weekly fee of 70 cents. But they soon ran out of money and by the time they visited the nursery again, the found it sealed with barbwire.

“All the babies had been taken away on Japanese trucks. If he’s still alive today, our son would probably be somewhere in Japan,” he said, of the heartbreaking memory.

Hunger numbed the loss in those desperate days. When a Chiuchow restaurant announced fresh pork buns would be on sale for 50 cents each the next morning, everyone, including Li and his wife, queued before daybreak.

“It was as big as a fist and the fillings were made of meat marinated with garlic and black beans. It was steaming hot and tasted great. We shared a piece and decided to get another one the next day. But the shop was closed and many Japanese soldiers were there. As it turned out, the meat in those buns was from dead human bodies,” he says.

Rice was collected on a ration coupon. Once, Li overslept and arrived at the shop late – and found only debris, the aftermath of a bomb.

“In the ruins I saw a human arm and a skull, I was very lucky again.”

Li had another narrow escape in Central. This time, an American bomber plane missed its Japanese target and landed its bomb on Wing Lok Street where the first Yung Kee, the roast goose specialist, was located. Li walked by and was hit by the debris.

But the real test of loss was to come for Li.

“After the loss of our sons, my wife gave birth to a girl in 1942. But the poor baby was weak probably from malnutrition and died before the full month,” he said.

Li sang at a teahouse while his wife sold second-hand clothes in Wan Chai and they heard used items had greater demand in Guangzhou.

“So we pooled our money and bought a ferry ticket for my wife to go north. That was the first time we parted since we married four years earlier.”

For the first four months, Li received letters and money – and then nothing.

“I missed my wife so much that I decided to go to Guangzhou for her. I organised a drama troupe of 23 members and we performed on our way toGuangzhou.”

When Li arrived in Guangzhou a few months later in 1943, his wife met him.

“I noticed she had her hair permed and had an amah. Then I realised she had re-married and was pregnant. We both cried but I was resolute in refusing her money. After she left, her amah left me with a bag of rice and in it there was a money order that was equivalent to HK$150,” he said.

To make ends meet, Li became a seaman and took part in smuggling, including opium. In one of the operations in Zhaoqing, he had an encounter with a Japanese sentry.

“They shot at me and I hid under the reeds and returned fire at them with my two pistols. It was all quiet after that. The next day people in the nearby town said two Japanese soldiers were killed last night, I think that’s me,” he recalls.

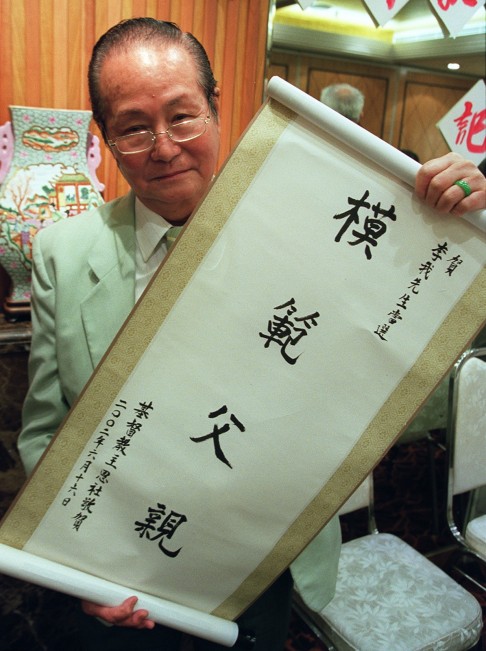

When Japan surrendered in August 1945, Li went back to school, to study politics and law at Lingnan University in Guangzhou. But he never finished it. He made HK$1 million in 1947 for his hugely popular radio shows. It was from there that he moved on to carve a legendary career as a broadcaster.

From the ruins of war, he met his new wife Shiu Sheung in 1949 and they moved to Hong Kong. They have a son and are proud grandparents of three children. This time, the love story endured.