Codename Castra: the Post reporter-spy who defied the Japanese during the second world war

Archives have revealed the secret workings of a former Post reporter who became an undercover agent in the wartime fight against the invaders

Dressed in her cheongsam and with her broad face sprinkled with freckles, Kay Chinn Mah appeared to be just one of the many working women trying to find their way in the crumpled city of Hong Kong during the war years.

But Mah hid a secret identity so well that even her grandchildren only learned about it after her death in 1997 at the age of 91.

During the second world war, little did those around her know that she took on multiple disguises, collected information and ventured into dangerous places that could have got her killed by the Japanese occupiers.

She was, in the words of her captain, "one of his best agents".

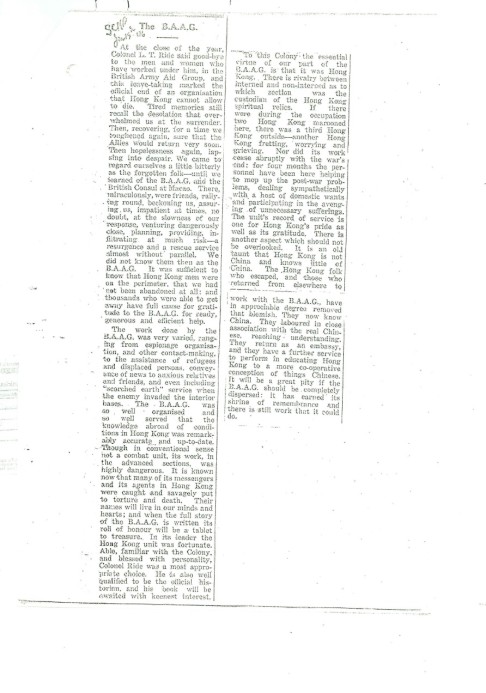

The secret life of Mah was unveiled through archives left behind by Colonel Lindsay Ride (1898-1977), founder and commander of wartime intelligence unit British Army Aid Group.

A collection with copies of the documents compiled by his daughter Elizabeth Ride from years of research, along with some artefacts, is available for viewing at the Hong Kong Heritage Project, while the bulk of the originals are kept at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

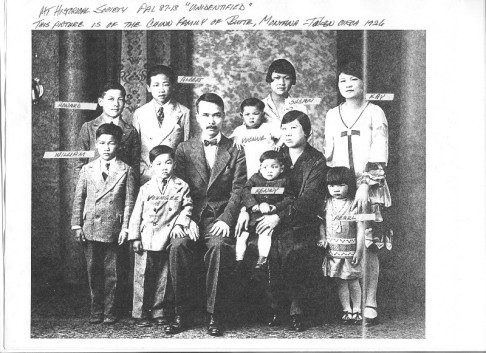

Mah was born Kay Chinn on March 15, 1906 in Sun Boye Village in Taishan , Guangdong province. Her paternal clan moved to America in 1875 and eventually grew into one of the most prominent merchant Chinese families in Butte in Montana. But Mah spent her early years in China and Hong Kong.

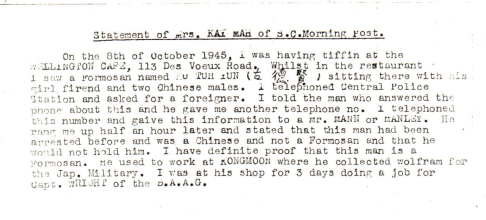

But Mah spent her early years in China and Hong Kong. When the second world war broke out, she was a reporter for the South China Morning Post, which, like many publications, had been banned by the Japanese.

Yet Mah continued to put her investigative skills to good use.

It was also during the war that she lost her husband, Mah Do Kun, who died in 1943.

"As a pre-war journalist she had a host of contacts at every level in Hong Kong, and, of course as a Toishan [Taishan] Chinese was a member of a very widespread but close-knit club," Major Colin McEwan (1916-1984) - to whom Mah reported in the BAAG - wrote of her in records now stored in the collection.

According to McEwan, he relied on Mah as a messenger and also profited from her reports on Hong Kong. She operated under the codename Castra - a fact Elizabeth Ride established by cross-referencing the files.

I gave no information to the Japanese Gendarmes and I believe I was released so I could be followed.

In a family friend's memory, Mah was often elegantly dressed in a cheongsam. But the archives revealed a brave side, such as when she would be disguised as a coolie or a smuggler in secret operations, or when she refused to disclose information to the Japanese even when captured and beaten up.

"She earned her codename by going to two of the offshore islands in the Canton delta where the Japanese were building fortified gun emplacements against a possible invasion by the American fleet," McEwan wrote.

"This operation started by her mentioning on one of her return trips from Hong Kong that she had heard that the Japanese were up to something on those same islands and she 'reckoned' that she could get onto the islands and, as a coolie woman, work on them and find out what it was all about. This she did and returned a month later with a description and a set of sketches which, my headquarters confirmed later, filled out the detail they needed to fill out the blanks on air reconnaissance reports."

The documents recorded her doing a survey of coastal shipping, trying to organise an underground ferry service from Hong Kong with a friend who was a trader, and posing as a smuggler to arrange the purchase of three junk boats.

Danger came when she was arrested by the Kowloon gendarmes of the Japanese and was beaten up and interrogated.

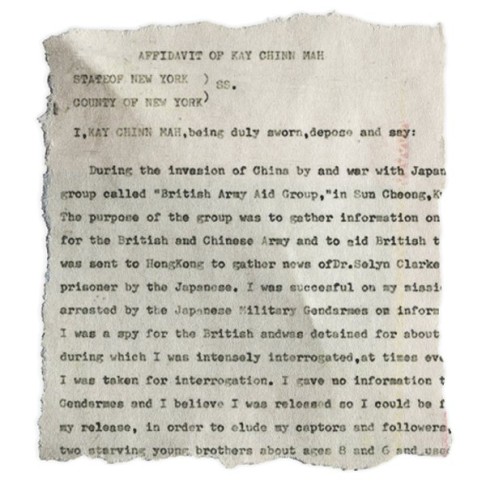

But the spunky Mah managed to bribe her way out, according to McEwan's papers. This was consistent with a personal account written by Mah years later, as seen in an affidavit her grandson Albert found and provided to the Sunday Morning Post.

"I was sent to Hong Kong to gather news of Dr Selwyn-Clarke who was taken prisoner by the Japanese. I was successful on my mission, but was arrested by the Japanese military gendarmes on information that I was a spy for the British, and was detained for about 40 days during which I was intensely interrogated - at times even at night I was taken for interrogation. I gave no information to the Japanese and I believe I was released so I could be followed," the agent wrote. The date of the document is unclear.

McEwan said Mah was "one of my pet agents" and "one of my best independent agents", and they were close friends after the war. His daughter, Meilan Henderson, now 67 and living in Scotland, recalled meeting Mah as a frequent visitor to their home.

"I remember Kay often visiting my parents in the 1950s and possibly the very early 1960s at our flat in Repulse Bay," Henderson said. "Kay was always lively and talkative, with what seemed to me a very strong American accent … As I recall, she usually wore a cheongsam.

"At the time I knew nothing of my father's or Kay's exploits during the war, or I might have paid more attention."

Henderson's younger sister, Alison McEwan, recalled: "She would always arrive with a gift of some sweets or cakes … but at that time we knew nothing of my father's wartime activities, and it was only after my mother's death - my father predeceased her - when I started looking into my father's papers that we realised who she was.

"She had a very warm personality, loud and quite bossy, in a friendly way. She was always looking for help for friends or acquaintances less fortunate than herself, seeing if my parents could help with advice, money or jobs. She was a large woman with a broad face covered in freckles, and seemed always in a hurry."

The South China Morning Post lost its pre-war staff records and thus little is known of Mah's journalistic career.

What is known is that after the war, Mah did not return to journalism but went into the antiques business. In August 1967, she left Hong Kong for Hawaii and became an American citizen in 1982, almost 15 years after migrating there. In her later years, she divided her time among her three children in Radford, Virginia, King of Prussia in Pennsylvania, and New York City. As she grew older, she spent most of her days and died in Radford, said her grandson, Albert Mah.

"Grandma and my father never really spoke about the war years to us. I regret now not having pushed a little harder to learn more of our family's history."

The research findings have forged renewed admiration for their grandmother.

He said: "Everyone was amazed at the information about Grandma and the war effort. There were always whispered rumours that she did things during the war, but apparently no one had any idea at all what she was involved in."

Next week: China's changing narrative on the Kuomintang