Why a job is more than just an income source for Hong Kong’s mentally ill

People with mental health issues still struggle to return to the workforce amid discrimination, although care providers say society is now more accepting

When the low budget Hong Kong film Mad World was chosen as a nominee for best foreign language film at the Oscars, it served as a stark reminder of the sobering reality faced by the mentally ill in the city.

In the family drama, actor Shawn Yue Man-lok plays a bipolar patient called Tung, whose hardship reintegrating into society reflects the plight of tens of thousands.

In one scene, Tung’s job interview ends in failure after an employer learns that he spent a year in a psychiatric ward.

Data from the Department of Health showed that 37,634 people with mental and behavioural disorders were discharged from local hospitals in 2015. Like in the movie, the stigma these patients carry with them often means employers are hesitant to hire them.

This was why for Neil Lee Yiu-wing, who suffers from schizophrenia, it was a breakthrough almost a decade ago when he managed to land a job as an office assistant with accounting firm Sky Trend CPA.

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder in which a sufferer may have difficulty distinguishing between reality and the imagined.

Founder Raymond Law Wai-man said: “My frontline staff were pretty concerned when I made that decision. They were afraid that hiring someone with a mental illness would add to their workload.”

According to Legislative Council documents, the Equal Opportunities Commission, the city’s equality watchdog, received an average of 95 complaints relating to discrimination against people with mental illness each year from 2011 to 2013. About 60 per cent of these happened in the workplace.

Law said: “I assured my other employees that they would have enough support [if Lee’s work was affected by his illness], and that our company had a social responsibility.

“He is a good worker,” Law added. “We also love laughing at his jokes.”

Now 44, Lee was diagnosed with the disorder when he was 26. He had felt extremely depressed after his grandmother died, and had to seek medical treatment.

“I thought non-stop about my grandmother every day for the first two years after her death,” Lee said. “My family was also having financial problems at the time. In my first job out of school, I was fired before the probation period ended ... My father later took me to the doctor.”

Mental health care in Hong Kong falls woefully short amid social stigma and lack of policy direction

Lee said he tried looking for another job after he was diagnosed, but he faced rejections all the time.

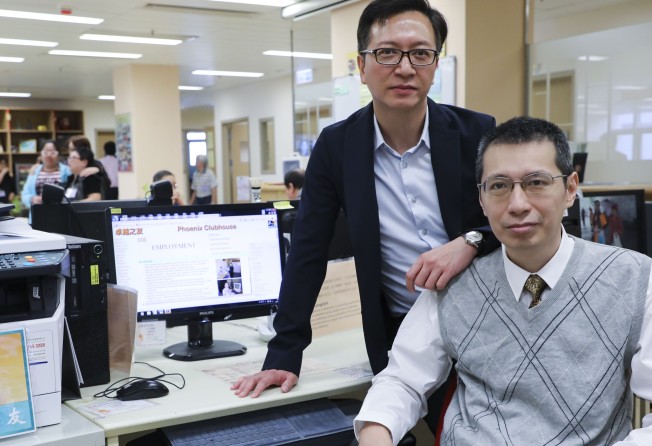

He finally turned to Phoenix Clubhouse, a psychiatric rehabilitation service under Queen Mary Hospital that helps people with mental health issues find work.

“A job is a form of recognition to mental health patients,” June Chao Yau-wai, the clubhouse administrator, said.

She said getting back into the workforce not only helped generate income for sufferers, but also allowed them to rebuild social bonds which they had lost while being isolated in hospitals for treatment.

“In Hong Kong, where your job pretty much represents your identity, imagine how you would feel when friends ask about where you work, and you can only say you are jobless,” Chao added.

The club, which is jointly run by the University of Hong Kong’s department of psychiatry and Queen Mary Hospital, provides three types of employment programmes, ranging from full time to part time jobs with mostly entry-level positions for members.

The services are offered in partnership with 52 companies in Hong Kong, such as Morgan Stanley, UBS and Hong Kong Land.

Since it was set up in 1998, the club has successfully helped reintegrate more than 250 people into the workforce.

Anita Chan Suk-fan, head of Phoenix Clubhouse, said people were now more accepting of workers with mental illness compared with 19 years ago when the programme was launched.

“Some companies are a bit reserved at first. They are afraid that people with mental health issues would become violent or that they may become stigmatised at work.”

“But after these companies take the first step in hiring them, their worries turned out to be unfounded.”