Shutting us down? We’ll just move to Causeway Bay, say some Mong Kok street performers

The characters of Sai Yeung Choi Street South have their say on controversial move to reopen street to cars

Dressed in a flowing black outfit and clutching a wad of cash in her left hand, Ling stands in the middle of Sai Yeung Choi Street South, belting out a Chinese ballad.

It is 8pm on a sweltering Sunday night in Mong Kok and the fiftysomething singer, silhouetted by neon and fluorescent lights, does her best to catch the attention of the passing throng of locals and tourists, their chatter drowned out by the cacophony of tunes blaring from portable speakers.

After her performance, talk turns to the impending full-time return of vehicles to the street – overturning a government move to regularly pedestrianise it 18 years ago.

Ling proclaims:“We will resist.”

“It is not worth killing the street for the small bunch of dissatisfied people,” the resident of Tuen Mun, more than 45 minutes away by MTR, says in a huff.

Mong Kok, a gritty, densely packed neighbourhood, is a warren of shops, street stalls, bars and food joints catering to myriad tastes and types of people.

It is also home to about 70,000 of Hong Kong’s residents, many cramped in flats tucked away on the higher floors of squat buildings lining the busiest streets, with others housed in micro flats in gleaming high-rise developments.

It is not worth ‘killing’ the street for the small bunch of dissatisfied people

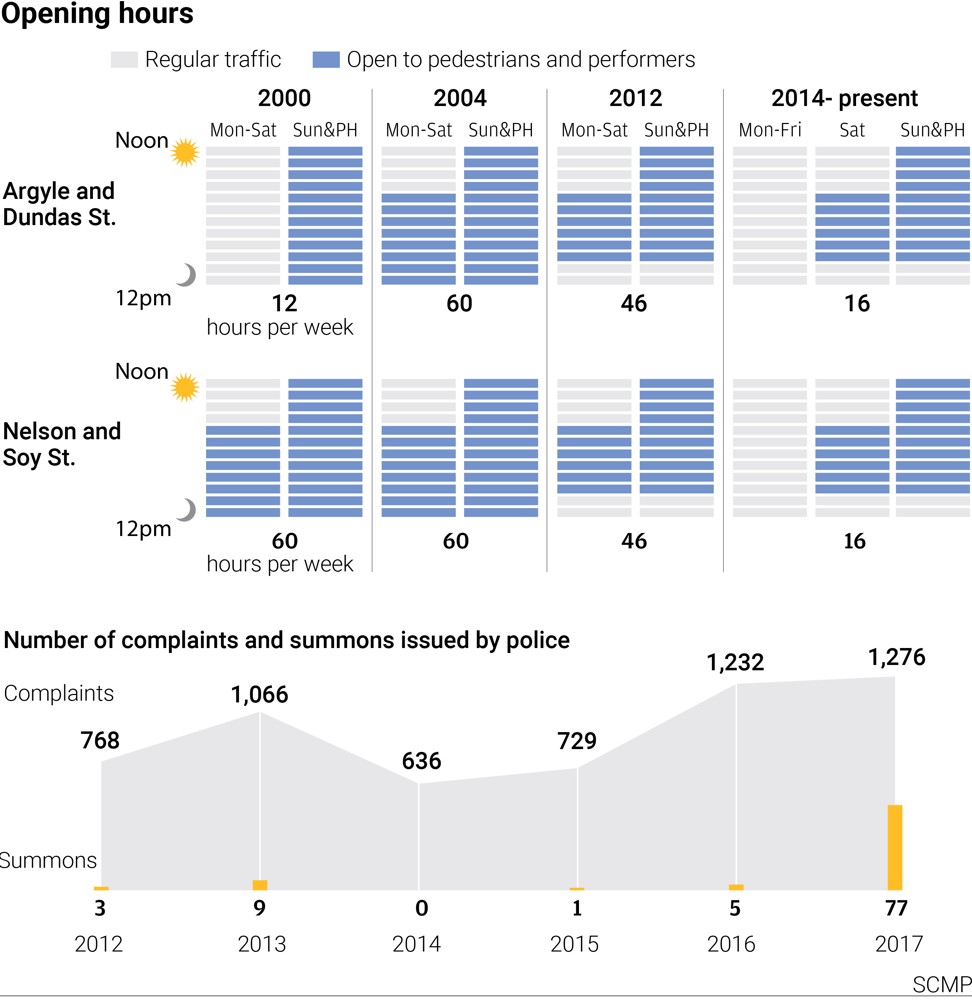

Last year, complaints to the authorities of noise and obstruction along Sai Yeung Choi Street South peaked at 1,276, up 66 per cent from 2012. This is despite pedestrian zone hours being progressively shortened over the years.

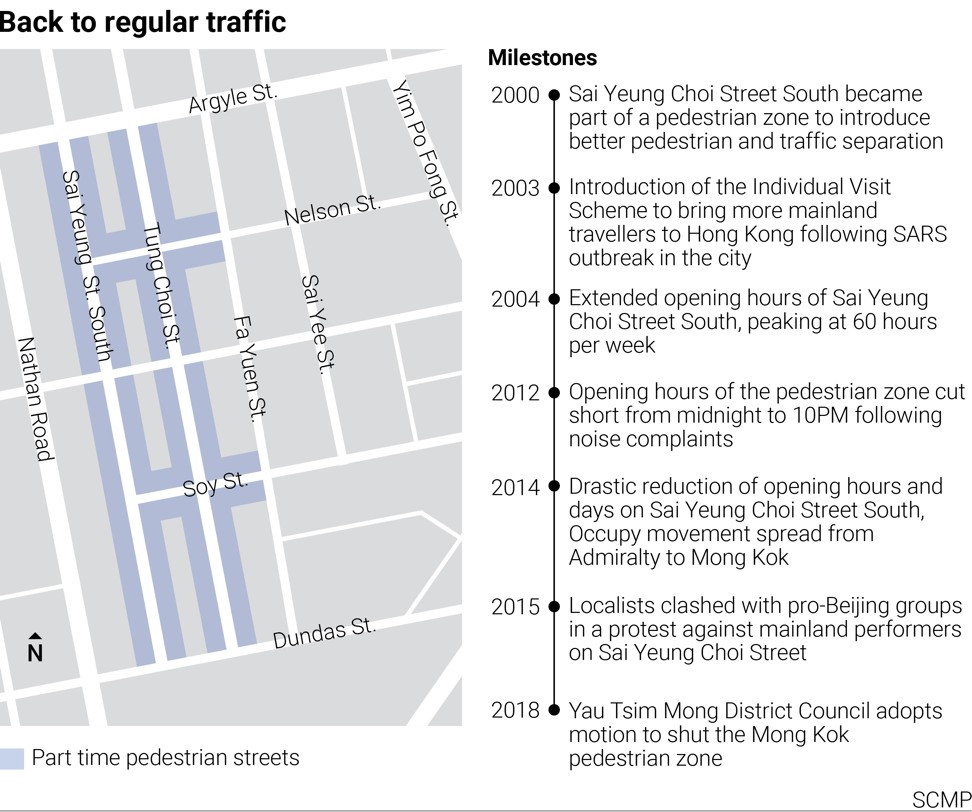

Since 2014, it has been closed to vehicle traffic for 16 hours a week – between 4pm and 10pm on Saturday and noon to 10pm on Sunday. At other times, vehicles can trundle down the road but cannot stop to unload goods or park.

Earlier this month, the Yau Tsim Mong District Council, which advises the government on community matters in the area, decided enough was enough.

District councillors, many from pro-government and pro-business parties, voted 15 to 1 on a motion to completely terminate the pedestrianisation scheme.

The ball is now in the government’s court to shut down the zone. But it has not confirmed when it will do so.

A Transport Department spokesman said it would first consult the public on the impact of the change and update traffic signs and adjust traffic lights, among other things.

From shopping hub to nightmare zone

District councillor Chan Siu-tong is feeling “deceived”. A member of the Business and Professionals Alliance, Chan said he supported the establishment of the zone in 2000 because the Transport Department presented a “beautiful picture”.

“[There would be no cars], the air quality would improve and the problem of pedestrians and cars fighting for [space on] the road would be solved,” Chan said last week.

The zone began as a 200-metre pedestrian stretch from 4pm to midnight from Mondays to Saturdays.

Desperate to boost tourism and retail numbers after business dived on the back of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) outbreak in February 2003, the department announced in January 2004 that the full 500-metre zone would be in force for 60 hours a week spread out over seven days.

But the plan to boost commerce through a vibrant street culture became a recurring nightmare for local businesses and residents.

Entertainers – ranging from middle-aged female dancers to caterwauling karaoke singers to buskers with guitars and amateur acrobats – began engaging in turf wars over who should stand where.

They soon began trying to outdo each other with zany costumes, antics and noise – a better-known character has been prancing around with his shirt unbuttoned and a Japanese spitz perched on his shoulders.

A survey commissioned by the Liberal Party had found that performers were as loud as 101.5 decibels. The Post found during a visit that the ambient noise was between 50 and 55 decibels. A hair dryer makes up to 100 decibels of noise and a screaming child is about 110 decibels.

One shop tried to block the noise with plastic barriers last year, but was ordered to take them down by the Buildings Department.

By 2012, pedestrian zone hours had dropped to 46 a week and this was drastically reduced in 2014. But the complaints only rose.

The area was also a flashpoint for trouble in the aftermath of the 2014 Occupy protests for greater democracy.

In 2015, localists clashed with pro-Beijing groups on Sai Yueng Choi Street South during a protest against the mainland Chinese dancers, resulting in the police pepper spraying protesters.

And during the Lunar New Year in 2016 a government crackdown on unlicensed hawkers on nearby Portland Street sparked the Mong Kok riot, when protesters clashed with police in a frenzy of violence. It resulted in the arrest of 91 people, many of whom are awaiting prosecution.

Hongkongers who have weighed in on the issue have acknowledged the tangle of problems the zone poses.

But they also point out shutting it down would mean the city losing a place of character, and noise pollution from off-key singers may just be replaced with noisy vehicle traffic.

‘Applause only and no tips, please’

At least a third of regular performers did not show up on the Sunday after the district council decision, councillor Andy Yu Tak-po from the Civic Party says.

“Two weeks ago, this place was still filled to the brim,” Yu says.

Indeed, at 8pm, there were about 25 groups of singers and bands, and fewer than a dozen others offering snapshots, fortune telling and sketches.

Among the music groups, most had two portable speakers blasting music at volumes ranging from 60 to 80 decibels. Most twirled and crooned in anticipation of easy cash.

And therein lay the problem, two men and a band of musicians claimed.

A male passer-by, who said he was retired and surnamed Yip, added he had never liked the group of female singers on Nelson Street as they had pushed out younger performers.

He claimed he was once propositioned by one of the female singers on Nelson Street. And indeed, the Post spotted women accepting money and red packets from men and handing them cans of beer in return.

“She asked me to take her on a dinner date,” Yip recounted, saying he turned the woman down.

“Mong Kok Law Man”, a 57-year-old with slightly bulging eyes and black hair who styled himself as late Canto-pop star Roman Tam Pak-sin, said there were “up to 10 groups” of middle-aged female dancers who had caused others to turn up their volume.

They “showed no respect for reasonable distance and performed next to entertainers when they first arrived at the street from Tuen Mun some 1½ years ago,” he charges.

He said having rules on what performers could do would limit the noise and “weed out low-quality shows”.

Some 10 metres from Law Man’s patch, another band called Sing a Song, who claimed to have been performing for free for a decade, said if the government forbade performers on the street to collect money from spectators, the problem would be solved as most of them would be gone.

“Applause only and no tips please,” said a sign the group had put up.

Keeping everyone happy

As a compromise, several district councillors have called on the government to license street entertainers.

Yu, during the council meeting last Thursday, suggested suspending instead of scrapping the zone, until licensing and regulation could be done. But this was shot down.

He recommended that street performers be required to go for auditions and their props examined to guarantee quality and safety.

“The street should also be divided into different zones for different performances and each performer can only occupy a spot for a certain period of time, for example two hours,” Yu said.

Cities such as Taipei and New York already license street performers, the latter requiring them to follow rules such as obtaining permits for using equipment such as amplifiers and speakers. Rules are stricter on the London Underground, where performers are first auditioned before being given a permit.

But more importantly, Yu said, Hong Kong needs laws to regulate street shows.

Yu added that the law on noise control should also be amended so that police officers could rely more on readings from decibel meters instead of collecting testimonies from the public when handling complaints against street performers.

But critics of the suggestion include performers who say they draw crowds precisely because they are spontaneous and unregulated.

Popular culture scholars suggested the government look at providing more public space and publicising behaviour codes for street performers.

“What we need is to re-educate the street performers and the public how to behave in public areas, instead of setting up a licensing system that requires performers to meet a certain set of aesthetic standards,” said “Ah Kok” Wong Chun-kok, a musician who lectured in universities on cultural studies before leaving last year for London to do a PhD in ethnomusicology.

Regulation can easily diminish diversity

He and Anthony Fung Ying-him, a cultural policy professor at Chinese University, said more public space should be provided for people with different cultural demands.

“Regulation can easily diminish diversity. A licensing system is a most stringent form of regulation. There are worries that some performers, such as foreigners, may lose their chances under a licensing system,” Fung said.

Elsewhere in the city, the West Kowloon Cultural District Authority launched its own street performance permit schemes in 2010 and 2015 respectively, both requiring applicants to demonstrate their acts to a group of judges and perform in designated spots. Some 398 permits have been given out since the 2015 scheme was launched.

In July 2010, the Leisure and Cultural Services Department launched an Open Stage Scheme in three venues – the Cultural Centre in Tsim Sha Tsui, the Kwai Tsing Theatre in Kowloon and Sha Tin Town Hall in the New Territories. Performers have told them that the scheme “has provided arts enthusiasts a platform which is suitably managed to showcase their talents”, a spokesman says.

So what next?

Some performers are sanguine about their fate.

Yu Pujiang, 70, who has been performing acrobatic tricks to Michael Jackson hits in the area for six years, said he would take a break and restage his show in other public spaces ranging from Tsim Sha Tsui’s Star Ferry Pier, to Lan Kwai Fong in Central, and Times Square in Causeway Bay.

Kim Hung, a 54-year-old male singer leading his group Hung Lok Goon, said he would move to another pedestrian zone, but did not name an exact location.

At least three groups of performers on Sai Yeung Choi Street South said they could stage their acts in other tourist hotspots such as Tsim Sha Tsui and Causeway Bay.

But this news has kept councillors of other districts up at night.

Wan Chai district councillor Yolanda Ng Yuen-ting, whose constituency is Causeway Bay, said she was “very worried” that incoming performers could add to the already crowded streets in the area.

Already, she said, a group of practitioners of Falun Gong – banned on the mainland for “heretical teaching” – have an ongoing stand-off with their opponents on Great George Street. The street is always thronging with people as it is in the heart of Causeway Bay.

“One side is displaying their ‘operating theatre’, the other has a blown-up ‘funeral hall,” Ng said.

The Falun Gong practitioners allege the Chinese Communist Party has been grafting and selling human organs. In protest, their opponents have set up a black inflatable altar with banners to signal the “death” of the group.

“It just makes people uncomfortable,” the district councillor said.