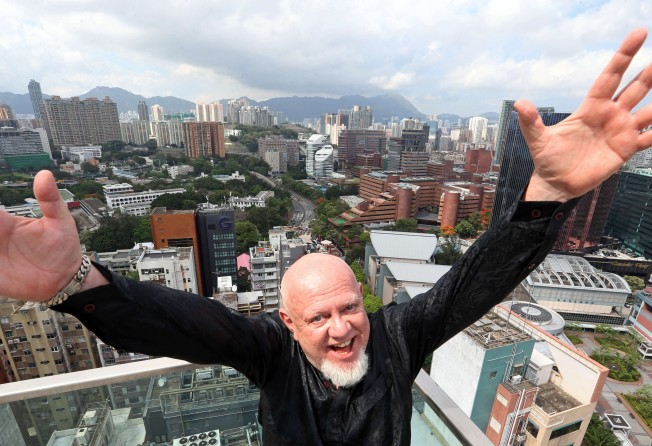

Hong Kong’s Swedish son Anders Nelsson turns 70

Anders Nelsson has been in Hong Kong for most of the time since 1950 imbibing the local culture, playing music and acting alongside superstars like Bruce Lee

Anders Nelsson had been vocal long before he turned 70 on Friday and thus officially became “a grumpy old man”. From road signs to recycling bins, the US-born Swedish music veteran always has an opinion to offer.

With 65 years in Hong Kong, Nelsson’s mastery of Cantonese and the subtle culture and tradition behind it often enables him to think inside and outside the box. His depth in the local culture was best demonstrated on the day of ATV’s closure last April when he was the only person to bow three times, a traditional Chinese ritual for the dead, at the front gate of the deceased TV station.

Like his music as a performer or composer, Nelsson is articulate in ideas based not on academic credentials but as an active participant in various fields throughout his long career – at one time as a journalist – since he recorded his first single in 1963 with his band.

In many instances he wore several hats at the same time, such as playing guitar for Bruce Lee while starring in a kung fu movie. Without saying it, he is a true descendant of the bygone “can-do spirit” of Hong Kong from the 1970s.

Of late he has been a consultant on the licensing of music and books on the mainland. To put his suspicious Chinese clients at ease over Elvis Presley’s hit song Hound Dog, a term they associated with “running dog”, a Cultural Revolution catchphrase for anti-socialist enemies, “I told them it’s about a guy calling his wife a bitch. Instantly they were relieved,” Nelsson laughed.

Behind the rant from the “grumpy old man”, Hong Kong’s adopted son always presents a big heart for the city he calls home.

Q: You were born in the United States and spent your toddler years in China. How did you end up in Hong Kong?

A: My parents were missionaries and they were sent to Changsha in Hunanprovince when I was just one year old. I was four when they left for Hong Kong on 18 November ,1950. My family settled in the New Territories. In those days or even now, Kowloon peninsula was regarded as the dark side, and the expatriate families of the government and bankers stayed in Mid-Levels, the Peak or Repulse Bay and rarely crossed the harbour.

Q: When did you start regarding Hong Kong as your home?

A: In 1963, my parents and siblings were relocated to Penang. But I was doing really well with my first vinyl single, which made it to the top of the charts. So I stayed behind. Two years later, when I turned 18, I was drafted into the military service in Sweden. I don’t know if I missed Hong Kong so much that I spoke in my sleep. And the mixture gabbling of Swedish, English, Cantonese and Mandarin drove my roommates crazy and they thought I was possessed by evil spirits. So I was discharged with the remark in the release paper that I was totally useless for all military purposes. With the hippy and peace movement at the time, I found that really cool. Juxtaposed between Sweden and America, Hong Kong was the base and my roots. The older I get, the more I become a Hong Kong person.

Q: Did you ever feel discriminated against in Hong Kong?

A: No, never. Perhaps I have always worked in the local culture and quite early on made an effort to learn Cantonese, which really helps in bargaining. The bands I played in were of mixed nationalities, including Chinese members. Especially when I came back from my military service, the whole band was Chinese except for me. Some expatriates felt offended when they were called “gweilo” (a Cantonese slang term which literally means “ghost-man”). But I find it very cute. I remember when I was a young boy going to a village in the New Territories, the Hakka ladies would say “hey, look at that gwei-zai (literally “ghost-boy”) and his pretty blonde hair”, and start touching my hair etc. So we grew up being called “gwei-zai” and then “gweilo” as we became older. Interestingly, the first person who called me “gwei-lo” in my face was Bruce Lee at a dim sum restaurant in Tsim Sha Tsui. He was already a superstar and I was invited to join him through his younger brother Robert, who was a band player. “Gweilo, are you free tomorrow morning?” was what he said to me. How would I say no to Bruce Lee? I ended up playing as one of the thugs in his film The Way of the Dragon. I still recall he asked me to bring my guitar to jam music during scene changes. His favourite song was Guantanamera.

Q: Would you say the 1970s and the 1980s were the golden era for Hong Kong?

A: I would say from the 1960s onwards, the city was very international. Apart from the mixture of peoples who lived here, there were so-called China watchers who were here because China was closed in those days, pundits and genuine journalists filing stories about China. My band played in a nightclub called the Bayside in the basement of Chungking Mansions. There was a coffee shop at ground level which was a hang out for China watchers, including some who worked their way to become very famous in overseas media. So it was an amazingly interesting time because of the influx of tourists to what was then called “The Pearl of the Orient”. Now I never understand why Hong Kong is no longer called “The Pearl of the Orient”. It’s now called “Asia’s World City”, which to me is meaningless. Many people are saying we are becoming less and less Asia’s world city. That’s true as we are losing out to Tokyo or even Shanghai now. But if we can still be “The Pearl of the Orient”, what’s wrong with that? The change of name is total foolishness.

Q: As an eyewitness, what do you see as the reason for Hong Kong’s success then?

A: Hong Kong was always a free port with very low taxation and virtually no import duty. There’s also what the government used to call a laissez-faire attitude towards setting up businesses. Although in name it remains the same, I find it’s getting more and more difficult with this or that regulation for, say, setting up a restaurant. Even if you follow every regulation, somehow they’d find something to make it difficult. But Hong Kong used to be the centre for, say, textile and clothing in the world and Tsuen Wan was full of manufacturers of all sorts of products. Whatever the world demanded, Hong Kong would always say, “can do!” and we never said no, very often with zero resources or very little capital, and just sweat, 24-hour shifts and the whole family pooling together to do something – maybe toys, plastic flowers, that needed assembly. The one ambition was to support the young generation to get better education and to study overseas.

Q: So what is the current scene now?

A: The middle-class kids have been spoiled by their parents who push them hard in their study, maybe too hard. Instead of having a “can-do” attitude, these kids seem to have a “give-me” attitude. Everything needs to be done for them. By the time they leave their parents, they then want the government and society to do something for them. Some indulge in speculation in property and stocks and get themselves into trouble. That’s kind of an unhealthy syndrome rather than the old days where it was, yes, we pooled together to make the family successful, and then the bigger family, which is Hong Kong, successful. Apart from the “can-do” spirit, I feel that we have lost a lot of attractions, and that needs to be brought back and revived ... The government somehow has to bring back the pride in Hong Kong that we had in those days, and the sense of belonging to Hong Kong, which means belonging to China, whether you like it or not.

Q: Where does Hong Kong go from here?

A: Well, major cities in China like Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu (成都) have distinctive characters and cultures of their own. Hong Kong somehow has reached a state of confusion of who exactly we are. We need to build our own character, but not fixing things up like a brand new Hollywood set, such as the new Star Ferry pier on the Hong Kong side. I hope people will come to realise the importance of keeping the heritage, the little that we have left. We have almost nothing left. I am starting to feel I am the oldest thing in Hong Kong now, apart from [RTHK 91-year old DJ] Uncle Ray. We need someone who thinks long term. Where will Hong Kong be in 2047? Will that be the end or the beginning of Hong Kong? Shouldn’t we make it a gradual change upwards rather than downwards? If we let things slide, we will become a third-tier Chinese city.

Q: What do we need to do now?

A: We are at a low point right now, with morale, politics, such as the upcoming elections and the next chief executive and so on. But I think I was born an optimist, and I believe Hong Kong can get back that “can-do” attitude. But the government will have to do some serious thinking. At the moment, everything is inside of the box, very few people, those in think-tanks included, think outside of the box or tanks. I have a lot of ideas to offer, but is that my job? Some ask me not to bang my head against the wall as the government will never listen. A good example of that is the suggestion I made to the last British governor Chris Patten that the road to the new international airport be called “Bruce Lee Boulevard”. He immediately asked his aide to write down that “jolly good idea”. And now what’s it called? It’s “Airport Road”. How creative do you need to be to think of a name like that? I think that pretty much sums it up. We need people who can think outside of the box and are more creative and clever than “Airport Road”.