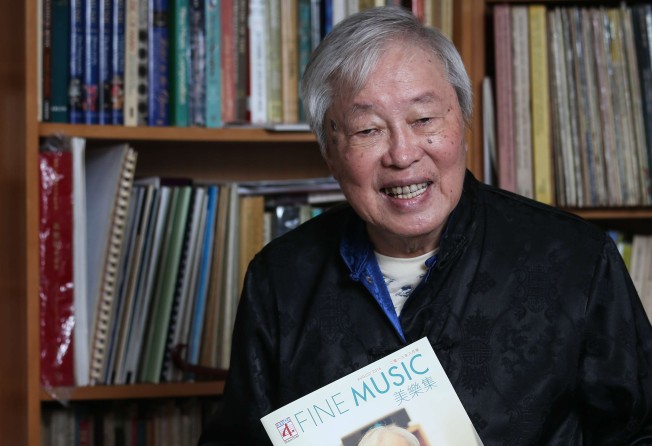

‘The father of Hong Kong modern music’ reflects on his award-winning career and fusing East and West in harmony

As he turns 90, Macau-born music maverick Doming Lam reflects on a life that has led to him being called the ‘father of Hong Kong modern music’

Veteran composer Doming Lam Ngok-pui has lived such a long life that he can causally say, “oh yes, [former broadcast chief] Cheung Man-yee was a presenter of my programme”.

Turning 90 this month, the Macau-born music maverick recalls many “firsts” in his long career in Hong Kong, starting with the variety show he produced at Rediffusion TV, a flagship station in the mid-1960s, which helped groom iconic figures such as Cheung and the late James Wong, a top showbiz songwriter and TV host.

Lam’s stint in television was no accident. He was among a privileged few, and the only Asian, in the master class of Miklos Rozsa, a three-time Oscar winning composer, whose credits include Ben Hur.

“It was destiny that a newspaper ad on his forthcoming class at the University of Southern California caught my eye,” the nonagenarian said, recalling the moment shortly after he graduated from the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto.

His three years in the vicinity of Hollywood exposed him to the world’s leading music-making experience. He also got to see “King of the Violin” Jascha Heifetz and his trio at work on the USC campus.

But it was a new music genre he picked up in Toronto that he aimed to brand as the music culture he felt Hong Kong deserved.

“I truly believed the time had come for a new musical language that used modern Western technique to reconstruct traditional Chinese music, and that was what we Chinese composers would [use to] interact with our counterparts in the world,” he said.

In 1973, Lam co-founded the Asian Composers League, a hub for like-minded composers from the region, and he chaired the Hong Kong chapter. In 1988, he led the League to join hands with the International Society for Contemporary Music to present more than 700 new works from composers around the world.

He is also an advocate of defending the intellectual rights of musicians, founding CASH, which stands for Composers and Authors Society of Hong Kong, in 1977.

As a composer, Lam’s first opus to fuse East and West was a violin sonata during his student days in Toronto, featuring elements of Peking and Cantonese opera.

The piece, subtitled Pearl of the Orient, a nickname for Hong Kong, was premiered in 1962 by his USC classmate Wang Tze-koong, who later played it at the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow.

With the rise of professional orchestras in the 1970s, Lam eyed new possibilities for his pursuit. But the results varied. A few he premiered with the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra had a far-reaching impact that inspired young composers in the mainland who had just come out of the Cultural Revolution.

“His works are extremely original and creative and at the same time closely linked with traditional Chinese culture … setting an example that has affected many young Chinese and Asian composers,” Tan Dun, an Oscar laureate, said.

Dubbed the “father of Hong Kong modern music” in addition to other lifetime accolades, the guru has few regrets.

Q: You were born in Macau but have been regarded as the godfather of Hong Kong composers. How did that happen?

A: I had my first musical training at the St Joseph Seminary in Macau. It was Father Smith, the music director, composer, conductor from Vienna, who took me under his wing. It was an institution to train Salesian missionaries, and music was a major part of the curriculum. But I was there only for the music. For four years I sang in the choir and picked up the violin at Smith’s suggestion. His music was very ear pleasing and I got to conduct the church choir, too. The only snag was Latin which I found very difficult to master. I left the seminary mainly because of that. It was around 1948 that I decided to come to Hong Kong, where there were more opportunities than Macau. I joined the Sino-British Orchestra as a violinist and its conductor Dr Solomon Bard took care of me. He deserved a lot of credit to hold the orchestra under meagre circumstances.

Meanwhile, I studied under Maple Quon, a piano alumni from the Royal Conservatory of Toronto, and that’s where I ended up in 1954 and finished with a diploma in composition in 1959. Those weekly presentations of new works really opened my musical horizons. So I tried it out in my own way to play traditional Chinese music using Western techniques. In The Lament of Lady Zhaojun, I used the piano to play the sound of pipa and guzheng, both plucked instruments. That was played by the Hong Kong Philharmonic, which presented a concert of all my works at the City Hall in 1965. It was a first for a local composer, and since then I have been associated with contemporary music.

Q: Was it conducive to your pursuit when orchestras turned professional in the 1970s?

A: Yes and no. The Hong Kong Phil, which became professional in 1974, did not show any interest whatsoever in local composers, and I think they still don’t. As for the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra, founded in 1977, they were aware of the scarcity of orchestral works for the new band. So they invited me to arrange traditional melodies into new scores and conduct. Music director Ng Tai-kong once rejected my arrangement for the famous ancient melody Moonlight Over the Spring River for piano and orchestra. Without looking at the scores, he said it was unplayable. But later he got a chance to listen to it at a concert, he came to me and said it was good stuff. ‘But you threw it away,’ I told him, and he responded with a reluctant smile. Since then it has become a standard repertoire and been recorded twice.

Q: Did you find it ironic that you studied Western music but ended up in a Chinese orchestra?

A: There was nothing I could do when Hong Kong Phil shut the door on me. I remember I was told it would play my work if I could write as well as Beethoven. To that I said if I could compose like Beethoven, I would be in Berlin or New York, not Hong Kong. The situation was different with the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra when the musicians helped me understand the sound and character of each instrument. Through trial and error, I gradually grasped the principles and put together my first major orchestral piece, Autumn Execution, in 1978. Many years later, in 1993, it was named a 20th century Chinese classic and an award was presented to me at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

Q: You were experimenting, but how were you so sure it would be a success?

A: I was aware of the impact of the experiment I was doing, that is, to give a symphonic form to a large group of traditional Chinese instruments capable of delivering harmony, counterpoint and so on. I also played up the different characters of each Chinese instrumental section. When The Insect World premiered in 1979, the sound of the bumble bees was imitated by erhu, a two-string fiddle. From a single erhu to a large ensemble, one could imagine the increase in volume and atmosphere.

Such a depiction using Chinese instruments was unheard of, and young composers in Beijing and Shanghai were stunned by the new sonic possibilities. A traditional Chinese orchestra has never been the same since. When the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra performed that work in 2002 at the Musikverein, the legendary golden hall in the heart of Vienna, it was very emotional to hear my work performed at the very hall of Beethoven and Mozart. It was not just an honour for me, but for all of us in Hong Kong.

Q: You were instrumental in taking Hong Kong composers to Asia and then to the world scene. How do you feel that we are now asked to look to the north instead?

A: Well, politically that’s the way to go, isn’t it? But I don’t think the two are mutually exclusive. My works are full of China elements, for example. So we Hong Kong composers should continue to look for the world’s latest compositional techniques and develop our own style and structure. At the same time, we take in Chinese ingredients and incorporate those into our works. We can learn technique, which is like one plus one equals two. But compositional style is something we work out ourselves.

Q: Do you have a word for the government and orchestras on behalf of composers, old and young?

A: We can’t quite expect the government to do something significant for composers unless someone in there knows music. Even if there’s such a person in the administration, there’s no guarantee. Professional orchestras like the Hong Kong Phil could organise a concert of new works by local composers every year. The opportunity to perform is the only way to motivate young talents to get serious about composing. It doesn’t do anyone any good if a new score stays in a drawer and never gets performed. To break the vicious cycle of a lack of quality local works, orchestras should take the initiative to work with composers.