Number of Hongkongers migrating to Canada hits 20-year high, stretching back to handover in 1997

But top diplomat in city declines to say whether political turmoil is reason

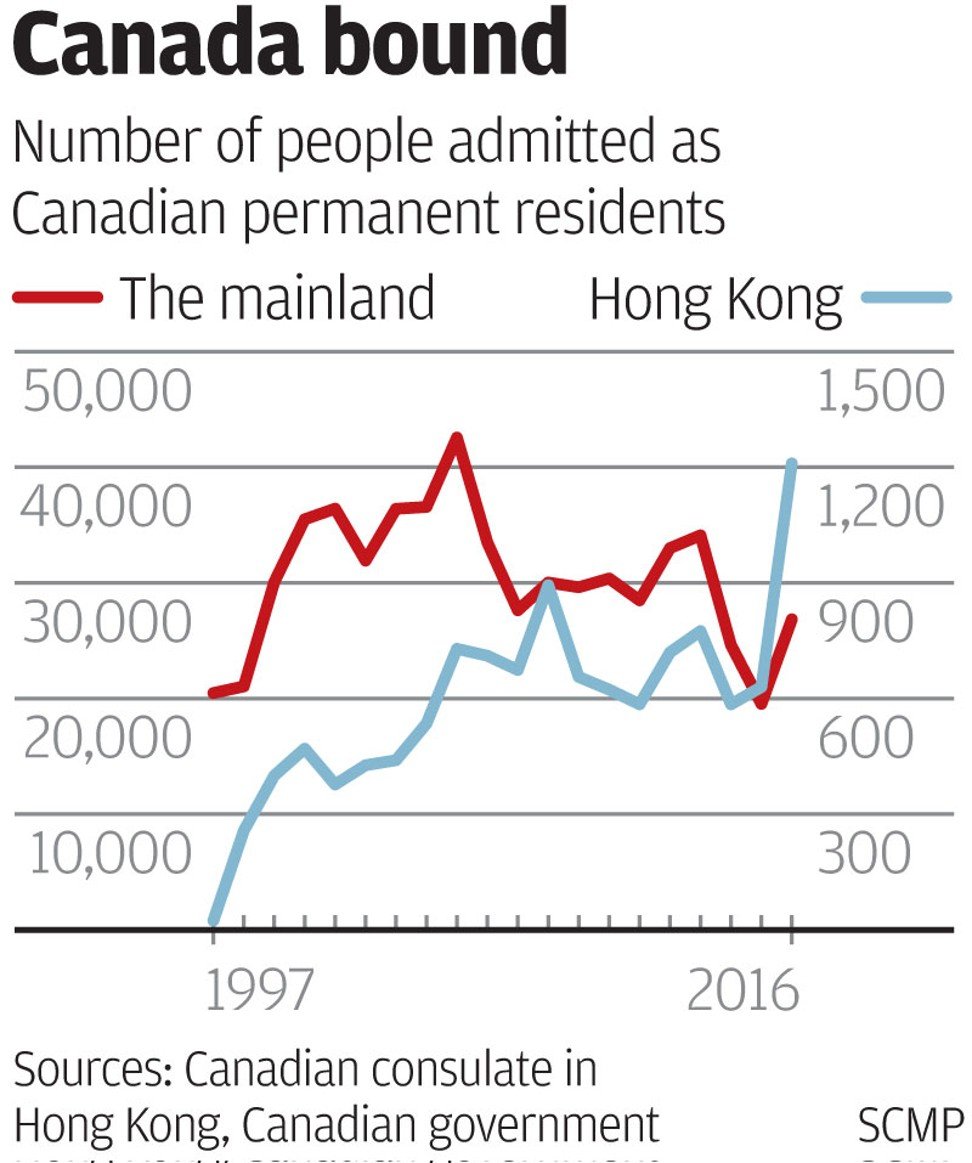

A record number of Hongkongers migrated to Canada last year in the biggest influx to the country since the 1997 handover, while more mainlanders made a similar trek despite the scrapping of a popular migrants scheme, the Post has learned.

Applications also spiked from 977 in 2013 to 1,481 in 2014, before dipping to 1,096 in 2015 and moderating at 1,194 in 2016.

“Hong Kong has changed a lot over the years,” said 34-year-old Ann Sze Ka-yan, who moved to Toronto last year. “Pressure at work was immense and children were also facing so much pressure at schools. Many parents did not want to be monster parents but they ended up that way. We felt that there was no point living a life like that.”

Many parents did not want to be monster parents but they ended up that way

Before Britain handed Hong Kong back to China in 1997, Hongkongers moved overseas in several waves, with Canada a popular choice. But in 1997 – the earliest year that records are available – only 24 Hongkongers became Canadian permanent residents. The figure rose to 257 in 1998, 400 in 1999, and has been in the hundreds since then, before peaking at 1,210 last year.

In the first half of this year, 660 Hongkongers took up such status.

Jeff Nankivell, the Canadian consul general in Hong Kong, would not speculate whether Occupy had played a role in the spike.

“The government of Canada does not ask applicants for their reason for immigration,” he told the Post. “Changes in numbers of entrants under different categories from year to year can reflect many factors, including changes in programme criteria and approved global volumes for different categories, as applied to applications that may have been submitted several years earlier.”

Nankivell said the figures showed Canada was a very welcoming place for people from Hong Kong and the mainland despite the scrapping of the federal Immigrant Investor Programme in 2014. That scheme, now replaced by one with stricter criteria, required applicants to loan the government C$800,000 (HK$5.14 million) interest-free for five years.

About 65,000 applications were axed then due to an “almost insuperable” backlog, the authorities said at the time, mostly filed by cash-rich mainlanders in Hong Kong.

“We are no longer implementing the investor immigrant programme as it was. But that doesn’t mean we are taking fewer immigrants. We are actually taking more overall,” the consul general explained. “Where we have expanded our efforts is in the area of skilled labour, so it’s not so much looking for a person who has money to invest.”

With more speakers of Mandarin than Cantonese in Canada now, what future for the southern Chinese dialect there?

Nankivell described the focus as one of “looking for a person who has skills that are needed in Canada, where people can be productive and contribute in Canada”.

“We have new programmes that are now making it easier and faster for people with those needed skills in areas including hi-tech.”

The number of permanent residents admitted through the skilled workers category, such as accountants and lawyers, surged by a factor of nine from 30 in 2014 to 275 last year. Investment immigration also tripled from 20 in 2015 to 60 last year. Admission from the sponsored family category – referring to those holding Canadian citizenship applying for citizenship on behalf of their family members – climbed from 395 in 2015 to 655 last year after the global quota was raised.

Meanwhile, 26,850 mainlanders became permanent residents of Canada last year, up 37 per cent from 2015. The most noticeable increase was in the sponsored family category, from 5,855 in 2015 to 9,070 last year. In the skilled workers category, the figure climbed from 3,730 to 4,885 over the same period.

Chinese elders’ immigration applications bog down in Hong Kong, and families in Canada wonder why

Dr Yan Miu-chung, director of the University of British Columbia’s school of social work, predicted the number of Hong Kong immigrants to Canada would grow in the years to come.

Yan, who migrated to Canada in 1993, said Occupy was a motivating factor.

“Many were asking themselves if Hong Kong was still a good place to live in,” he said. “Those whose children were studying in secondary school were asking themselves if they wanted their kids to pursue tertiary education in Hong Kong. There were also the factors of air pollution and high property prices.”

“We hope that people who want to express themselves politically in a peaceful way would not feel discouraged in the future by this development. It’s not a criticism of the court’s decision or of the process. We were expressing our hope that there will not be a wider impact that would have negative effects on the climate in Hong Kong for healthy political debates in the future.”

Nankivell added that he believed the “one country, two systems” principle was “very much alive” in the city, saying it had been through “many eventful years”.

“Hong Kong has always come through and Hongkongers have always come through. I approach every issue in Hong Kong with a spirit of optimism because I am optimistic about the people of Hong Kong.”