Fish bladders, bird saliva and a phallic seabed critter: would you eat these odd Chinese delicacies?

Centuries-old Chinese dishes come with their mix of mystery, myth and medicinal properties to whet your appetite ... or wean you off them for good

From stinky roadside tofu to animal innards, scorpions and snake soup, it may seem to outsiders that everything is fair game when it comes to Chinese food. But while those with an adventurous palate and strong stomach may be up for anything, not all unusual dishes come cheap.

City Weekend explores four delicacies served at Hong Kong restaurants that may tickle your food fancy – or make you think twice – depending on the stories behind what you are willing to put into your mouth.

Fish maw

With shark fin becoming a taboo, fish maw, or dried fish bladder, is the replacement ingredient in a crucial soup dish at Chinese wedding banquets.

Because of its high nutritional content, fish maw is regarded by the Chinese as a precious food, similar to abalone.

The fish bladder is a gas-filled organ that allows the animal to adjust its buoyancy in the water and right itself at various depths without having to expend energy using tail or fin movements.

Rich in proteins, calcium and phosphor, fish maw is believed to have beneficial properties – increasing stamina, strengthening the kidneys and helping to restore vigour. It is also believed to have rich collagen content with anti-ageing benefits, and is used in skincare products for women.

The delicacy is tasteless, but its texture and perceived health benefits make it a treasured addition to Chinese soups.

It is sold in dried strips, prepped and ready to be soaked and boiled in soup. Dried fish maw can vary in price from a few thousand Hong Kong dollars to over HK$60,000 (US$7,600) per kilogram depending on quality.

Fake fish maw is often encountered in markets, with imitations made from dried remains of other creatures such as squid.

According to global conservation body WWF, 3,272 tonnes of fish maw were imported into the city last year, with a total value of about HK$2 billion.

Such is the love for fish maw in Hong Kong that some endangered fish species, such as Mexico’s totoaba, are also hunted for their bladders, sparking concern from conservationists.

The Mexican government has banned totoaba fishing since 1975, but illegal poaching persists. In 2015, conservation group Greenpeace found that 13 seafood stores out of 70 it visited in Hong Kong were still selling bladders of the threatened species.

Bird’s nest

A well-known Chinese delicacy, bird’s nest soup is made from the dried nests and the saliva of the swiftlet, a small and endangered bird from Southeast Asia.

Bird’s nest has been prized for more than 400 years for its rarity, perceived nutritional benefits and anti-ageing properties. When dissolved in water, the nests take on a gelatinous quality that make them perfect for soup.

According to the Suiyuan Shidan, the Qing dynasty manual of gastronomy, bird’s nest must not be tainted by anything strong in flavour, smell or oil. It is believed that Zhen He, a Ming dynasty exporter and diplomat, was the first person to consume bird’s nest soup.

Throughout Chinese history, many emperors and royals have taken to the dish. The Empress Dowager Cixi, who was influential in the late Qing dynasty from 1861 until her death in 1908, was said to consume up to seven types of bird’s nest daily.

Today, the huge demand for bird’s nest – traditionally collected on precarious seaside caves and cliffs where the animals breed – has spawned farming industries in Southeast Asia, from Myanmar to Vietnam and Indonesia.

The trade is not without its controversies. There have been concerns about over-farming and cruelty, with animal lovers contending that undiscerning pickers may destroy nests still containing eggs or hatchlings.

Hong Kong and the United Sates are the largest importers of the delicacy, with rates as high as HK$16,000 per kilogram for white nests, and HK$80,000 for the extremely rare blood-red bird’s nests. In local restaurants, a bowl of bird’s nest soup can be priced up to HK$800 a bowl.

High costs have attracted many counterfeiters, and as a result, many quality control measures.

In 2011, China suspended bird’s nest imports from Malaysia following the detection of nitrates in the products, sparking food safety concerns and triggering a collapse in market price.

But the two countries later signed a deal in 2016 for the import of raw, untreated bird’s nests into China. Under the agreement, Malaysian farmers have to follow certain safety standards before the raw nests can be shipped over for cleaning and processing in China.

Because it is an animal product, bird’s nest trade is banned in some countries, especially over concerns of bird flu. For example, bird’s nest imports are prohibited in Australia unless a permit is issued.

Sea cucumber

While they may sound like a marine vegetable, these spongy-looking bottom feeders are actually animals with an evolutionary path tracing back more than 600 million years, with over 1,700 subspecies. Only 40 types can be consumed after cooking.

As with bird’s nests, the sea cucumber is listed in the Qing dynasty’s Suiyuan shidan as an ingredient with little taste and a difficult preparation process. Despite the trouble, and its unsavoury appearance, the sea cucumber is still regarded as one of the most treasured Chinese delicacies.

Dried sea cucumber is rehydrated and cooked in soups or stews, with numerous perceived health benefits including for treating arthritis, cancer and tendinitis. Books dating back to the Ming dynasty praise the sea cucumber for its benefits to male sexual health because of its phallic shape.

As with many Chinese delicacies, the growth in demand has meant sea cucumbers are considered to be at risk from overfishing. But their threatened status only increases their allure, giving rise to a vicious cycle.

Despite increased regulations, certain species of sea cucumber can be sold in markets for as much as HK$24,000 per kilogram.

Last year, international media reported on a “growing and lucrative” illegal cross-border trade. A father and son were charged for allegedly smuggling more than US$17 million (HK$133 million) worth of sea cucumbers into the US, then exporting them to Asia.

In 2015, a breakthrough study in genetics by Chinese scientists was reported in which researchers successfully mass-produced the white sea cucumber.

White “albino” variants are a rare mutation that occurs once in every 200,000 individuals in the wild. This rarity makes the white sea cucumber weigh in at a price per gram that is higher than gold.

Researchers at the time said they could not yet accurately estimate the white sea cucumber’s future market price. But the scientific fascination with harvesting sea cucumbers and the exorbitant market prices are testament to continued demand.

Donkey skin

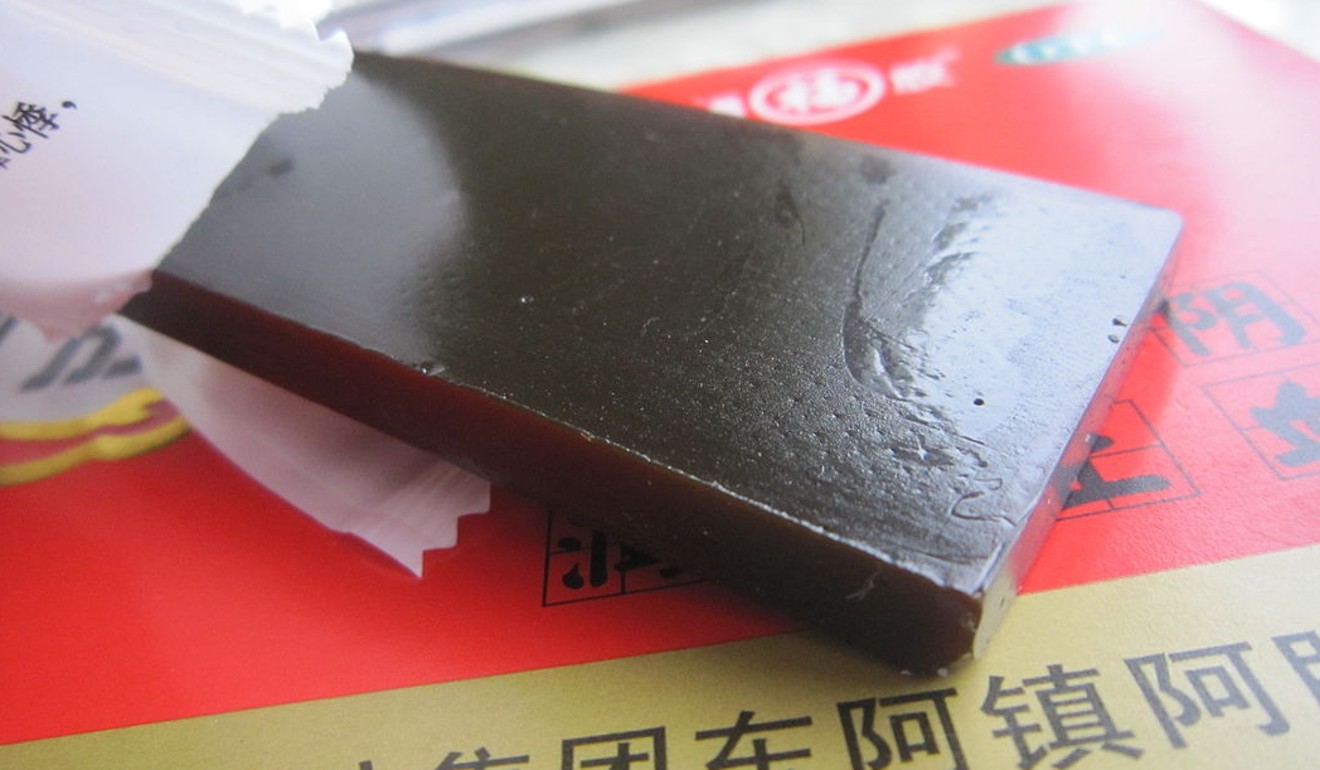

Ejiao, or the gelatin from donkey skin is a delicacy in Chinese traditional medicine, believed to bring skin-enhancing benefits. Donkey skin is also a popular blood tonic, thought to help in blood deficiencies or to alleviate heavy menstrual flows.

On January 1 this year, state-run news agency Xinhua reported that sales tax on donkey skin was reduced from 5 per cent to 2 per cent because of soaring demand.

According to industry estimates, sales of donkey skin products in the region rose to 342.2 billion yuan (HK$392 billion) in 2016 from 6.4 billion in 2008. A report by The Guardian last year cited figures from Britain’s Register of Chinese Herbal Medicine, stating that about 1.8 million donkey hides were traded annually worldwide.

High demand has raised ethical concerns over the excessive slaughter of donkeys in developing countries – where communities rely on them for livelihood – for shipment to China. Some animals are also reportedly stolen from their owners and killed for the trade.

The steady increase in demand for donkey skin has halved the recorded population of the animal in China since 1991.