This Hong Kong scientist wanted to discover new ocean species. He found 7,300

- Among discoveries from eight-year study is marine acidobacteria, which can be used to edit the genes of other organisms, previously known to exist only on land

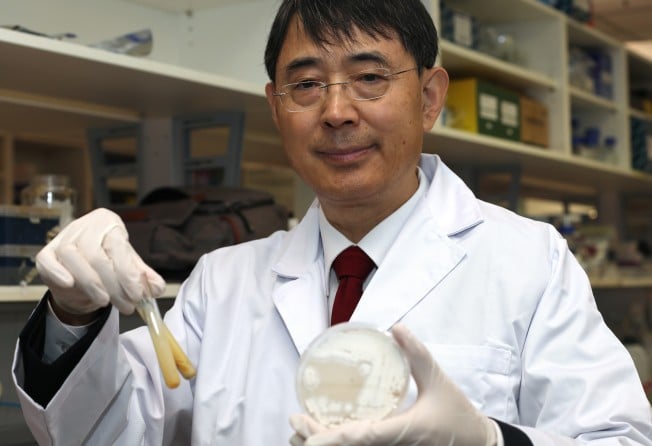

In 2011, Qian Peiyuan set out on a mission to measure the true biodiversity of microorganisms in the world’s oceans. What he discovered, in his words, could enhance the understanding of life and provide new weapons in the fight against disease.

Back then, the Hong Kong-based scientist was convinced the number of microbial marine species had to be higher than widely thought, and still thought more remained undiscovered when the international Tara Oceans research project put it at 35,000 in 2015.

His team scoured the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans, and the seas off Hong Kong. After eight years of study, they had discovered 7,300 new kinds of marine microbe.

That was just the amount found in underwater “biofilms” – collections of microorganisms that cover almost all moist surfaces, from ships’ hulls to teeth.

And researchers got more than they asked for, with the fortuitous discovery of a new type of bacteria which they claim could help scientists develop new drugs and antibiotics.

“Our primary goal was to try to understand or find out exactly how many microbes there were that were not discovered by the Tara Ocean programme,” said Qian, acting head of the ocean science department at the University of Science and Technology, and a zoologist by training.

The Tara Ocean project was carried out by an international consortium of scientists between 2009 and 2013 to survey microorganisms and plankton in the world’s oceans.

“Our thought was, maybe biofilms are a completely different type of marine habitat [from seawater], providing a completely different type of biodiversity. We found very diverse microbes in the biofilm.”

Among the surprises was the discovery of acidobacteria, a kind of bacteria loaded with gene-editing capabilities in its DNA, which had previously been known to exist only in soil on land.

Qian’s team essentially found the marine-based version by accident.

“This was incidental; it was never our intended target,” he said. “We just happened to find this unique phylum [of bacteria] commonly found in terrestrial environments.”

Acidobacteria contain gene clusters in their DNA sequences known as “CRISPR”, which can be used to edit other organisms’ genes, Qian said.

Such gene-editing systems are already being used by scientists to develop antibiotics and anti-tumour drugs, or engineer pollution- and natural disaster-resistant crops.

“This basically increases the arsenal of gene-editing systems for human application,” Qian said.

“These species have big potential in terms of facilitating our understanding of [life science] and offering new clues in our search for new treatments for diseases.”

The study was jointly conducted with researchers from Saudi Arabia and Australia. Its findings were published recently in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

Microbiologist and co-researcher Dr Zhang Weipeng said the new strain of CRISPR could help resolve sequencing shortcomings of terrestrial acidobacteria, namely its “accuracy issues”.

“Acidobacteria is just one of the many newly discovered microbial species in this project. With further in-depth study I am sure there will be more exciting finds to come,” he said.

The team believed new species of microbes would probably be found by increasing the sampling of biofilms from different ocean habitats.