Carer for mentally ill by day, musician and painter by night – Hong Kong man channels plight of the misunderstood into art

- See Wai-chung, also known by his stage name C Chung, tries to see things from the perspective of patients, and has had his share of emotional troubles

On his first day of work at a mental health rehabilitation centre, carer See Wai-chung recognised a familiar face among the patients – the vice-principal of his primary school.

“He acted exactly like the gentle, soft-spoken man in my memory. There was nothing wrong from his appearance,” recalls See, who later found out the man was seriously depressed.

See says the encounter spurred him to reach out to patients with respect and sincerity.

By day, See is a full-time carer for the mentally ill at a centre for the Mental Health Association of Hong Kong in Kwun Tong, teaching music and drawing to those striving to recover from depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and more.

According to its website, the association receives about 10,000 patients a year.

By night, the 32-year-old, with his floppy hair and tattoos, is very much an artist in his own right, being a musician and rock music composer, as well as a painter. He goes by his stage name C Chung, and is expecting to launch his ninth art exhibition soon.

See says working at the rehabilitation centre “has been a blessing”. “I get to hear so many fascinating stories about life,” he says on his inspiration for art.

Some 226,000 patients diagnosed with mental illnesses received treatment from the Hospital Authority in 2015-2016, according to a government report. A Department of Health survey in 2015 stated that nearly one in seven ethnic Chinese Hongkongers aged 16 to 75 suffered from mental disorders.

“I am no professional social worker or counsellor, but I guess my looks and tattoos somehow make me more relatable in the eyes of patients,” See says.

I am no professional social worker or counsellor, but I guess my looks and tattoos somehow make me more relatable in the eyes of patients

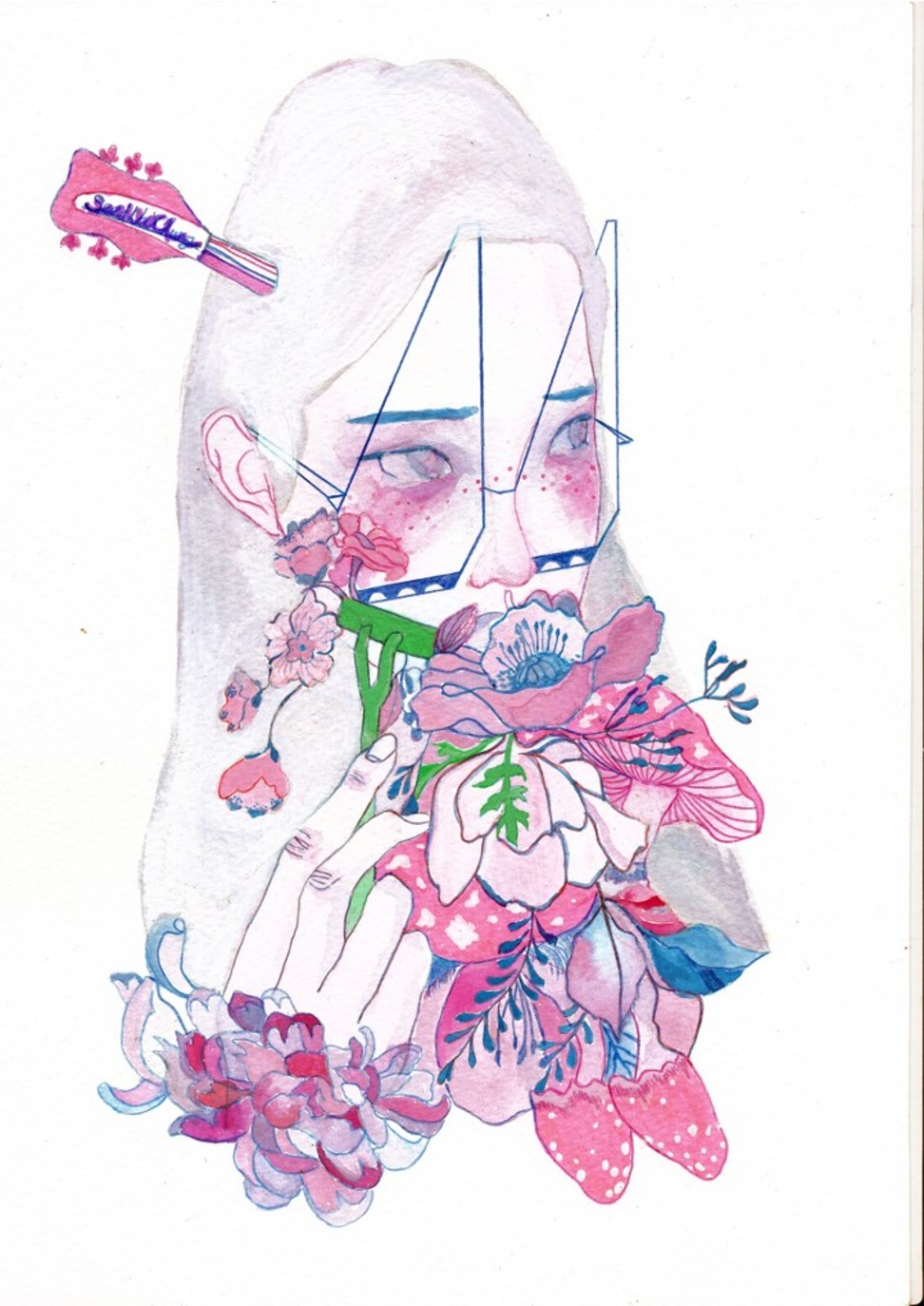

In his paintings, he often depicts the minds of those cast out in society as “crazy” or “monsters”. In his music videos, See belts out songs about hallucinations, anxiety and loneliness – challenges mental health patients often live with.

“I dress myself up like a weirdo in music videos essentially to tell people that everyone is weird or ill in a sense,” See explains. “Therefore, no one should be judged for who he is, and you can feel free to loosen up and find outlets for your feelings.”

When he was in his 20s, See struggled to make a living as a freelance illustrator with a college degree in design. When an artist friend mentioned a job opportunity in 2013 that “only requires teaching music and drawing”, See took the leap without even bothering to find out more details.

He received training at the centre on different types of mental illnesses before conducting classes where he would teach recovering patients.

“Even though I know some students are mentally troubled, it’s hard not to feel offended or disrespected when being cursed at by an adult,” See recalls of his early sessions.

He gets around this by initiating conversations with them to understand their mood swings better.

“It took me a while to realise that their rebellious attitudes are often not against me, but rather from a deeper cause.”

“There was this grandpa who would spend four hours on one painting, and get really grumpy when stopped. But he is just a perfectionist with obsessive-compulsive disorder. So I would just accompany him and let him finish.”

For See, getting to know patients is more about bonding than merely offering help. “Most students are older than me, and they've had rich experiences in life that I can learn from. So I will talk about my problems too, and get advice from them about saving money or career planning. It can be awkward at first, but many actually long to share.”

Such exchanges, according to See, give him a closer relationship to those he cares for at work.

Kit Ng, 32, who has been taking medication for depression since a suicide attempt in 2017, says See helps her to “get rid of the prejudices about mental illness through which I used to define myself”.

Having attended See’s music class for more than a year, Ng has formed a band with six fellow patients called Full of Hope. Through connections from the rehabilitation centre and See, they have performed a dozen times at malls, nursing homes and community centres.

“When I first met See, I was like: is he really a carer?” recalls Ng, laughing. “He seems relaxed and honest, and doesn’t mind working overtime to help our band practise. It makes you feel appreciated, like he’s not here just for the job.”

As a carer, See says he is no stranger to emotional problems. Last year, a patient with bipolar disorder committed suicide at home right after calling him. The two had known each other for five years.

“It was in the afternoon, and we talked over two hours about his newly diagnosed tumour, broken marriage and discrimination by relatives. It seemed everything was shattered for him,” See recalls.

“In the end he said: ‘Thank you for listening to me, bye’. That voice still haunts my dreams.”

The grief and guilt See then experienced prompted him to see a therapist, while also triggering a sudden bout of eczema. “Things just got too real for me, and that’s when I learned to stand in the shoes of a mentally troubled person.”

In retrospect, See still questions whether he could have done more to save a life, but concludes that in the end the patient was the only one who could save himself.

“It takes a strong will to confront your issues and ask for help,” See says, adding that the workaholic culture in Hong Kong is a ticking time bomb for most people experiencing stress.

“My art is meant to say that you should dare to express and try things out. Because after all, you’ve got only one life.”

If you, or someone you know, are having suicidal thoughts, help is available. For Hong Kong, dial +852 2896 0000 for The Samaritans or +852 2382 0000 for Suicide Prevention Services. In the US, call The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on +1 800 273 8255.