No shortage of ideas to boost land for homes in Hong Kong. But do Carrie Lam and Beijing have the political will to overhaul the system?

- In a new series delving beyond the social unrest in Hong Kong to survey the city’s deep-rooted problems, the Post is focusing on the role of housing in causing great disaffection in society

- In this third instalment, we look at the high land price system that has contributed to today's problem of unaffordable housing and the array of solutions available to the government if a complete overhaul is a bridge too far

The Hong Kong government caused a stir this week when it withdrew a sizeable plot of waterfront land from sale after rejecting five apparently low bids. But the canary in the property coal mine had been Goldin Financial Holdings, which walked away from the same project three months earlier.

The developer forfeited its HK$25 million (US$3.2 million) deposit when it gave up on the HK$11.1 billion plot at the former airport in Kai Tak, just two days after an estimated 1 million people took to the streets to oppose the government’s doomed extradition bill.

Abraham Razack, Goldin’s independent non-executive director and a pro-business lawmaker who was manhandled in the legislature when the bill was about to be scrutinised, blamed “social contradictions” – a euphemism for the looming troubles over the legislation – and the impact of the US-China trade war.

Putting up a tough front, the government doubled the bid deposit to HK$50 million to deter further snubs by developers. But on Wednesday it had to withdraw the site after it found no buyers willing to cough up its reserve price, as market watchers warned of developers getting cold feet amid the continuing social unrest.

Once again, the impact of the protests on the golden goose of property in Hong Kong has become a talking point, with property tycoons coming under mounting pressure to do their part to defuse the tensions. Beijing has made plain its disappointment with “vested interests” whom it accuses of hoarding land or thwarting the government’s land policies. Through its party mouthpieces, the central government said the lack of affordable housing was fuelling the increasingly violent clashes.

As the city approaches the 17th weekend of protests, with the impasse between demonstrators and the government appearing as unbreakable as ever, some analysts and the establishment elite have begun mulling the need to forge a new social compact, with housing as a central plank.

All the talk, however, might be too far in the distant future for the protesters, who insist their demands are not about housing but a call to stop alleged police abuse and implement universal suffrage. Still, others argue that deep-rooted socio-economic ills have dimmed the sense of hope and ownership of the city among many, protesters included. Discussion is now focusing on the need for real reforms to solve the severe housing crunch.

Housing in Hong Kong is inextricably tied to many other things, from a government heavily reliant on land sales for revenue to an economy held up in large measure by property behemoths with tentacles in a myriad of other sectors.

It is a common perception that the Hong Kong government not only rakes in revenue from land sales but also jealously guards that source of income by maintaining a system that keeps prices sky-high. Revenue from land-related proceeds and stamp duties has made up as much as 42 per cent of total annual government income in recent years. It is projected to drop to 33 per cent, or just over HK$197 billion, in the current financial year.

Land-related revenue has enabled the government to deliver, among other things, a massive public housing programme that has helped Hongkongers who cannot afford private home prices. However, the scarcity of land in recent years has not only driven up prices but also resulted in public housing projects being delayed, longer waiting times for flat applicants, and festering discontent.

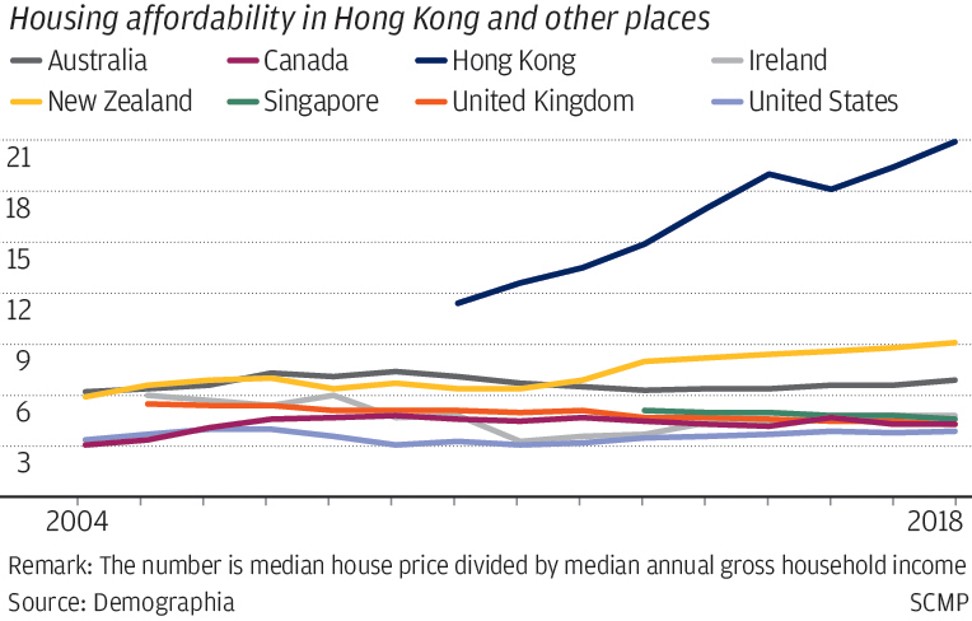

Through it all, Hong Kong’s home prices have soared, reaching levels that are the highest in the world and well beyond the reach of aspiring homeowners.

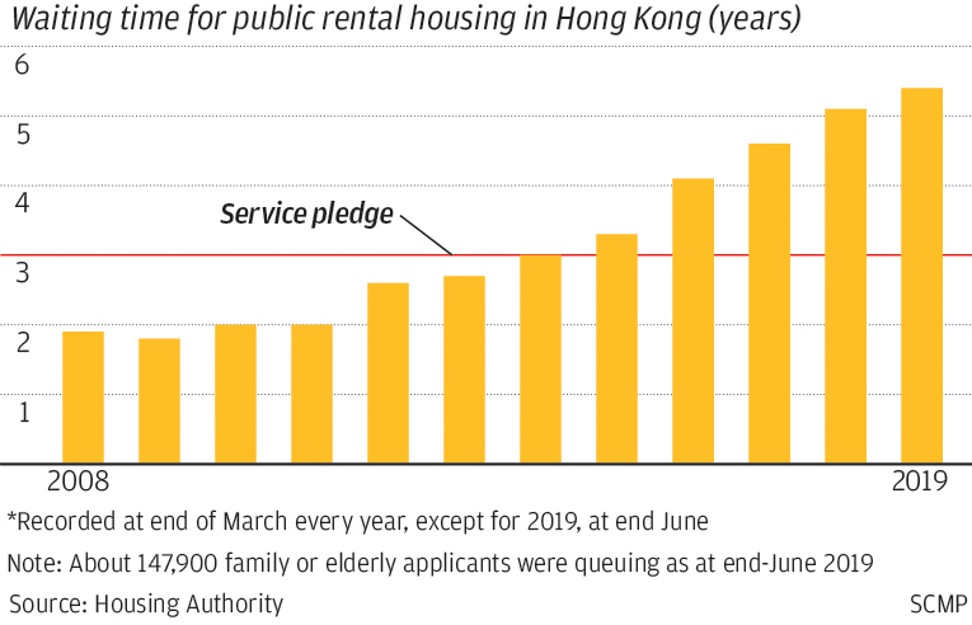

Even those hoping to rent a subsidised public flat have to wait 5.4 years, much longer than the promised three years. In the meantime, many live in old, substandard and subdivided flats (as small as 70 sq ft), which are tinier than public rental homes yet cost considerably more each month.

Observers say Hong Kong needs nothing short of an overhaul of its entire land supply system for residents to have more affordable housing. Some even support the idea, endorsed by Beijing through the state media, of the government taking back land from developers.

An entrenched – and lucrative – land sales system

Hong Kong’s land policies go back to colonial times, when the British decided all land would be sold on leasehold, with strict conditions on use and plot ratios for every lease.

The government collects massive sums from outright land sales to private developers. It earns more from various taxes, including stamp duties from property transactions and charges for any alteration to a lease, or change of land use.

The system became entrenched and has proven too lucrative for successive administrations to seek alternative revenue streams.

If there were few objections to the system over the years, some academics say, it was because ordinary people then had access to subsidised homes for rent or sale, through a large-scale public housing programme that was not under the strain it is facing now.

But over the decades, the land sale system also reduced competition to a handful of powerful developers, who were adroit enough to amass banks of rural land cheaply in the past few decades.

Patrick Lau Lai-chiu, a retired official who was lands director from 2002 to 2007, said it was unfair to blame the government for setting high prices.

Pointing out that only a small number of government land sales failed to attract buyers over the past 50 years, he said: “This demonstrates that the prices are what the market will bear. One must not forget that land has always been in short supply.”

In the past five years, six land sales were cancelled due to bids falling below the reserve prices, including the Kai Tak site, with three of them later completed.

Lau added that it made business sense for developers to aim for a good profit margin and pass on the high land premium to buyers.

Overhauling the system would be difficult, he argued, especially if the government is expected to lower land prices overnight.

Aside from the hit to revenue, he said, there would be nothing to stop developers from pocketing the lower land premiums and still charging high prices to buyers. That might be avoided if a developer decided, in the name of corporate social responsibility, to lower home prices and kick-start a price war – a “rather unlikely” scenario, Lau believed.

He warned that any sudden fall in prices would have a negative impact on the value of existing homes. Half of the population owns property and could become vociferous in their opposition to an already unpopular government, should their homes drop in value.

If you shake up the real estate sector, the consequences on society as a whole will be profound.

Lau Chun-kong, a surveyor and member of the government-appointed task force on land supply which published its report last year, said reforming the land sale system required “major surgery” impossible to execute overnight.

“Unless someone is able to throw in a new economic framework that will work for Hong Kong, I can’t see the basis of a fundamental shift or an overhaul of the high land price policy which has been around for such a long time,” he said. “If you shake up the real estate sector, the consequences on society as a whole will be profound.”

Time to take back land from developers?

In determining that unaffordable homes were the root cause of the ongoing protests, Chinese state media have also targeted the city’s big developers. In editorials and commentaries earlier this month, they urged the Hong Kong government to adopt an idea floated by the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB) and take back land hoarded by developers and use it to build public housing. The DAB, the city’s largest pro-establishment party, suggested invoking the Lands Resumption Ordinance to do so.

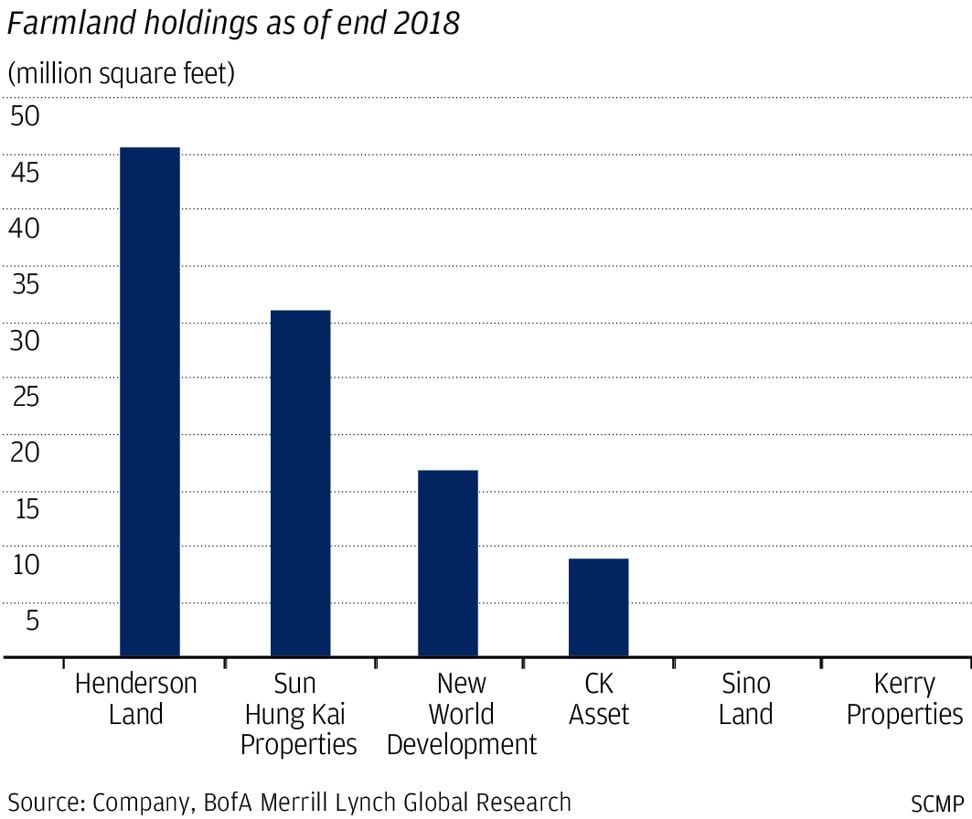

The task force on land supply estimated that developers hold a combined farmland stock of 1,000 hectares. If the government acquired just 150 hectares, it could build 170,000 public homes within 10 years. To give an idea how much this could help, the government earlier projected a land shortfall of 1,200 hectares, an estimate seen as “grossly conservative” by the task force.

The DAB was not the first to suggest using the ordinance. Last year, opposition lawmakers made the same suggestion to Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor. Responding coolly to the idea then, she warned that using the “imperial sword” to seize land risked legal challenges from developers. Indeed, developers had in the past threatened to sue when the government proposed taking back their land for a new town.

Lam proposed a “land-sharing” scheme instead, promising developers quicker approval for projects if they handed over a portion of the flats for public housing.

Three of the landowners holding the most rural land stock appear to be making gestures to yield to Beijing’s pressure. New World’s third-generation tycoon Adrian Cheng Chi-kong on Wednesday announced it would donate 3 million sq ft – almost a fifth of its land bank – to the government and to non-profit organisations for public housing and other purposes, hoping to benefit 10,000 people.

Sun Hung Kai Properties said it was prepared to hand over five to seven plots in Hung Shui Kiu and New Territories North already zoned for subsidised housing, but made clear it would oppose the government seizing plots set aside for private residential and commercial purposes, or land not yet zoned. It also said land resumption should be coupled with an “infrastructure-led” approach to developing new areas.

It wants the government to build transport infrastructure – including a promised railway line to connect the northern New Territories to the city centre – at the same time as homes are being built, rather than waiting until people move in.

The task force on land supply supported this approach, which was accepted by the government, but implementation plans have yet to be mapped out.

On Thursday, Henderson Land Development, the largest private owner of rural land, said it would not object if three of its plots totalling 1 million sq ft in Fanling, near the border with Shenzhen – and already zoned for public housing – were acquired under the land resumption law.

The last holdout thus far has been CK Asset Holdings, owned by one-time Beijing darling Li Ka-shing. The company, whose billionaire leader has faced what he called “unwarranted” attacks by Beijing’s political and legal affairs commission over his relatively sympathetic stance towards anti-government protesters, said it would look into the idea. But it added that converting farmland for housing would “take a longer time to benefit those in need”. CK Asset also stressed that Li had over the years donated HK$25 billion to different social causes, including education and research.

Whether the gestures by the developers are token or tangible remains to be seen. And even as more developers decide to give peace offerings of land donation, analysts argue that land resumption should not be set aside or viewed as a last-resort tool of the government, but one to be used routinely for more effective planning.

Task force chairman Stanley Wong Yuen-fai is among those who support such a bold move.

“If there is a private plot near public transport services and it is so sizeable that it can hold a public housing estate rather than a single block, the government should first engage the developer for a ‘partnership’ talk. But if that bears no fruit, it should not wait any more, and resort to land resumption,” he said.

He added that the compensation rate for acquired plots, now at HK$1,349 per square foot for agricultural land within planned new towns or affected by major projects, could be made more attractive to win over developers. “But this shouldn’t mean the ‘hope value’ of the land should be given,” he added.

The risk of legal action remains and former lands director Lau said: “From a political point of view, it might not be a bad thing if a judicial review is initiated by a developer. If the government loses, critics can no longer say the government is not willing to resume developers’ land.”

A person familiar with land and housing mechanisms said the ordinance would be useful for fast-tracking small or medium-sized public housing projects. But taking back developers’ land to build a new town would not help much in creating homes more quickly, because planning is a lengthy process involving many legal procedures.

The ordinance was used, for example, to acquire land for some parts of the ongoing Fanling North/Kwu Tung North new town project, but it took a decade for land resumption to start last year, the person said.

“There are many misunderstandings about the use of this land resumption power. It may not be as much of a quick fix as it seems,” the source said. “In fact, it seems dangerous to me to use the ordinance against certain landowners, rather than objectively looking at the sites suitable for public housing.”

If not land resumption, then what?

The task force last year recommended eight short- and long-term options to source land, including Carrie Lam’s ambitious reclamation scheme off Lantau Island, intended to create 1,200 hectares, which sparked controversy because of its hefty price tag of HK$500 billion and 30-year time frame.

Lam showcased the Lantau reclamation plan as her government’s once-and-for-all solution to the land shortage problem, but it was soon overshadowed by the extradition bill protests.

Other options have also been raised. The Liber Research Community, a housing think tank manned by people in their 20s and 30s, has advocated the redevelopment of brownfield sites, abandoned farmland used for things such as waste recycling and scrapyards. It estimates there are about 300 hectares of such land that can be used for public housing blocks of six to 12 storeys, providing homes for 250,000 people.

The group’s founder, Chan Kim-ching, said: “The brownfield policy has been discussed for three to four years, but the government has still not yet revealed the brownfield land policy framework that it promised. You can see it has been procrastinating.”

Ng Cheuk-hang, spokesman for the Land Justice League, an activist group, believed there would be more land freed for public housing if the Urban Renewal Authority (URA) changed its approach.

The URA has long been criticised for acting like a developer, because once it identifies a site for redevelopment, old residents have to move out and only the rich can afford the new homes that come up.

Its “flat-for-flat” strategy for affected residents has not worked, because it either takes too long for the new flats to be ready, or the replacement flats offered in Kai Tak are surrounded by construction sites.

Ng said the government should subsidise the URA to build public rather than private housing on redeveloped sites.

The Our Hong Kong Foundation, a think tank founded by former chief executive Tung Chee-hwa, has proposed looking to Singapore’s housing model, suggesting that boosting home ownership is the key to narrowing the wealth gap and pacifying young people.

On Wednesday it suggested a package which, it claimed, would raise the city’s home ownership rate from 49 per cent to 70 or 80 per cent. One measure would see the government spend 20 per cent of land premiums it receives every year to provide interest-free loans for first-time buyers aged under 40.

It also called for the revival of the Tenants Purchase Scheme, which Tung introduced in 1998 to help people become homeowners. Managed by the Housing Authority, it allowed tenants on 39 estates to buy their flats. The think tank said the scheme should be expanded to cover all 181 rental housing estates, and be enhanced to incentivise tenants to buy the flats.

Under the proposal, after tenants buy a flat, they would be allowed to resell it on the private market later at a much lower premium than before. This would stimulate turnover and allow people to move up the property ladder, the foundation argued.

But Stanley Wong, also chairman of the Housing Authority’s subsidised housing committee, had reservations about both the loan and the expansion of the Tenants Purchase Scheme.

The loan scheme, he said, would not break the back of the problem of high property prices. “The young people getting the loan will still need to spend a large portion of their salary paying the monthly mortgage,” Wong said.

“I don’t think this is what young people want. There’s talk among them of refusing to be ‘property slaves’ or working for developers for their whole lives.”

Wong also said the tenants scheme could be seen as unfair, as those now living in those flats would get more benefits than others.

The ball is now in the Housing Authority’s court to decide on these suggestions. Last month, it indicated it was open to the idea of selling the remaining 44,100 unsold units on the 39 estates covered by the original scheme, but did not commit beyond that.

Can Beijing help in other ways?

Beyond these options, Beijing itself might be able to do more to help ease Hong Kong’s housing crunch, analysts say.

A major property developer who declined to be named said two areas worth considering for public housing were a 60-hectare site reserved for Disneyland’s second phase and part of the People’s Liberation Army’s Castle Peak firing range, a vast 2,263-hectare piece of barren rocky land in the northern New Territories, which featured in a recent PLA promotional video showing various anti-riot drills of the Hong Kong garrison.

“Both Disney and the firing range are immediately buildable. No need for reclamation, no need for land premium, and no need for negotiations with developers or villagers,” the developer said.

“The central government can use this to show its love and care to Hong Kong citizens. It’ll be a win-win-win situation.”

It is a pity the government has not shown much progress after we delivered our recommendations report 10 months ago

The idea to tap military land was raised by a member of the land supply task force last year, but officials said none of the 19 military sites were “idle”. Critics believed the government might have been reluctant to be seen exerting pressure on Beijing.

While the list of ideas to boost supply is long, analysts say not enough attention has been paid to the demand side of housing. For as long as speculative activity is not curbed and tighter oversight of foreign ownership not exercised, the pressure on pricing will not ease.

While such curbs could work on regulating demand at the higher or private property end, some opposition politicians also argue that making it tougher for one-way permit holders from mainland China to get into the rental housing queue would reduce the competition for homes among the lower middle class and the poor.

Andrew Wan Siu-kin, Democratic Party lawmaker and spokesman on housing policy, for example, suggests reducing the number of mainlanders arriving on the one-way permit scheme, as they accounted for 20 per cent of the total number of applicants for public rental housing last year. Right now the figure is 150 arrivals per day but in some years, that number is not reached on average.

But whether it is a review of demand or supply of land, the decision on land policy is predicated on political will, not just on the part of Beijing but also that of the local government. Here, the nexus of dependence between the government and property developers – who wield considerable influence on the election of the city’s chief executive and through its support of pro-business lawmakers – will also need to be recalibrated, analysts say. The revamping of housing and land policy will require a realignment of political power.

“Housing and land problems clearly existed long before the current social movement broke out, and we haven’t emphasised enough how urgent it is to tackle it with determination and resources,” Stanley Wong said. “It is a pity the government has not shown much progress after we delivered our recommendations report 10 months ago.

“But in the upcoming policy address, the government must demonstrate it has the resolve to really start to attend to the housing problem.

“I won’t say this will be enough to address the demands of the protesters, who also have political appeals. But at least it will help ease some tension. After all, the social discontent is underlying in the outrage.”

Lam will deliver her annual policy address next month. She has made clear that aside from withdrawing the extradition bill that triggered the protests, she is not giving in on the protesters’ other demands. Government sources say she will try to steer attention away from the turmoil to focus on social issues, especially housing.

The Liber Research Community’s Chan said: “Plenty of tools have been suggested to the government. Technical or political challenges are expected for each of them, and it’s just a matter of whether Carrie has the will to carry them out.”

Additional reporting by Lam Ka-sing and Gary Cheung