Court order on officer data targets doxxers not journalists, Hong Kong police insist

- Senior cybercrime officer rebuts claims that news reporting will fall foul of interim injunction granted on Friday to prevent personal information being shared

- He says it will only affect people who use leaks to ‘attack and intimidate our officers’

The Hong Kong police force’s short-term court order against publication of officers’ personal information was not an abuse of power or a blanket ban targeting the media, it has insisted, saying it was only to protect its staff from doxxing.

The force also said it would notify the most popular social-media platforms and messaging apps of the order, which would require them to remove any published personal information that could breach the injunction.

The force got the interim injunction from the High Court on Friday. That sparked uproar, legal experts saying its scope was so broad that it would expose a lot of people, especially journalists, to legal risks. The order will be effective until November 8, when a second hearing will be held to consider an extension.

In an interview on Saturday, Superintendent Swalikh Mohammed of the Cyber Security and Technology Crime Bureau said the order was a stern deterrent and would raise awareness among members of the public who think it is lawful to dox officers.

The leaks, he said, had affected officers’ work and caused stress to their families.

“The whole purpose of the injunction is not to target journalism and genuine reporting. Journalists can continue with the usual reporting practice in Hong Kong without fear of being affected,” Mohammed said, adding that the injunction sought to restrain anyone who “unlawfully and wilfully” posts personal information without consent. It also prohibits acts of harassment or intimidation.

“There is no specific offence called ‘doxxing’,” he continued. “Now the court order clearly spelled out such acts as unacceptable. Even people who are displeased with police actions cannot use doxxing as a means to attack and intimidate our officers.”

Since early June, protesters have regularly taken to the streets in a movement of anti-government discontent sparked by opposition to a controversial extradition bill. The actions have repeatedly led to clashes with police, who have used water cannons, tear gas and rubber bullets in the face of protesters setting fires and hurling bricks and petrol bombs. Two officers have hit protesters with live rounds.

Fury at police is common among protesters and their supporters, who accuse officers of overly aggressive tactics.

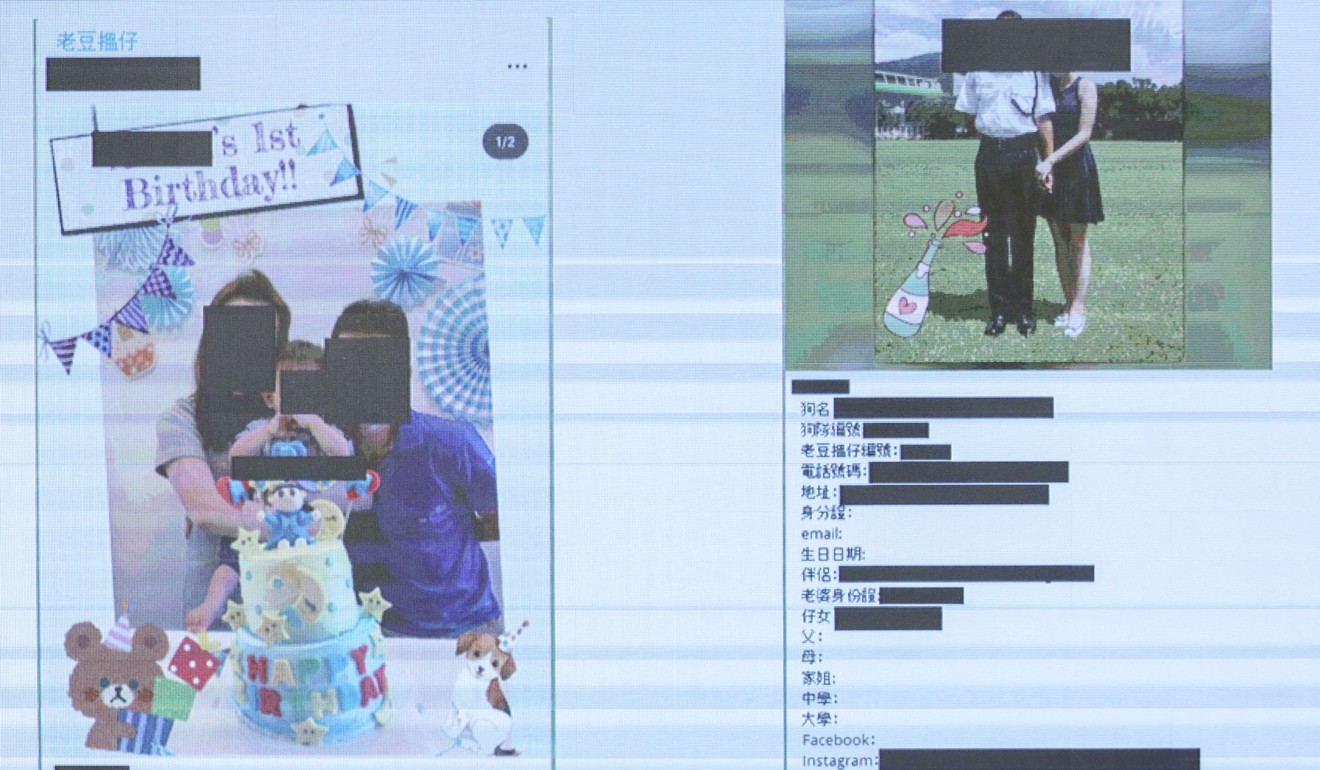

Between the start of the protests and Saturday, the bureau received 2,608 reports of doxxing from officers and their families, arresting 11 people in connection with them. The biggest single case came in July, when two men were arrested and accused of doxxing more than 600 police officers.

An inspector who gave his surname as Lee said that not only was he doxxed online for three months, but his younger sister was too.

During a protest in July, Lee protected his colleagues as protesters hurled objects at them. Later that night, his and his sister’s personal information went viral online. Lee got up to 300 phone calls per hour from people looking to harass him. Though he did not pick up, it was enough to drain a fully charged battery.

He said his sister had to get psychological help after protest supporters went to her workplace to find her.

“At that time, the protesters said to us it was OK to throw things at us, we would not die. I served the city and was doing the right thing. I do not understand why even some of my friends would leak my personal information,” Lee said. “Being a policeman is not a job, but a passion. The court order offers us protection. Those who doxxed us deserved a punishment.”

Mohammed added that in the worst doxxing attacks, protest supporters disclosed the schools of an officer’s children, and threatened to kidnap them and hurt anyone who got in their way.

“The force will work with the social-media platforms to remove contents that are in breach of this injunction,” he added.

The injunction banned the publication of 13 kinds of information related to police officers, including but not limited to names, addresses, telephone numbers, account names on social media, and photographs of officers and their family members without their consent.

It also forbade “intimidating, molesting, harassing, threatening, pestering or interfering with” any officer or their family, or causing others to do so.

Marcelo Thompson, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong’s faculty of law, said the writ “seemed to go too far” as it sought to establish a general requirement of consent for the use of personal data that is nowhere to be found in the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance. He also raised the worry that journalists’ reporting could fall foul of the injunction.

“It does seem to prevent the protesters from disclosing information relating to police officers to the media, even in legitimate cases,” Thompson said. “Indeed, it prevents disclosure to any person — with no reference to a mental element or the consequences of the disclosure.”

Privacy commissioner Stephen Wong Kai-yi said the current privacy law did not cover two key acts banned by the interim injunction – the publication of the personal details of officers or their families for harassment or intimidation, and aiding and abetting such acts.

“The existing privacy law only regulates the disclosure of a person’s information without the person’s consent which causes psychological harm to that person. When we enacted the law, there wasn’t a phenomenon of doxxing,” he said.

However, he said the privacy watchdog could still help implement the injunction, such as by getting involved in prosecutions and making relevant warnings to the public as well as the police.

He said that, since June, he had received some 2,370 complaints about doxxing, 694 of them from police.

Wong also said there was a need to amend privacy laws to enhance protection against doxxing as well as its punishment.

“We are thinking to increase the law’s deterrent effects and to update the law to cover doxxing. At present its maximum punishment is only a fine of HK$1 million and a jail term of five years, which we think is insufficient,” he said.