Explainer: what will China’s national anthem law mean for Hong Kong?

Beijing wants to regulate use of the national anthem, with strict penalties for those disrespecting the song

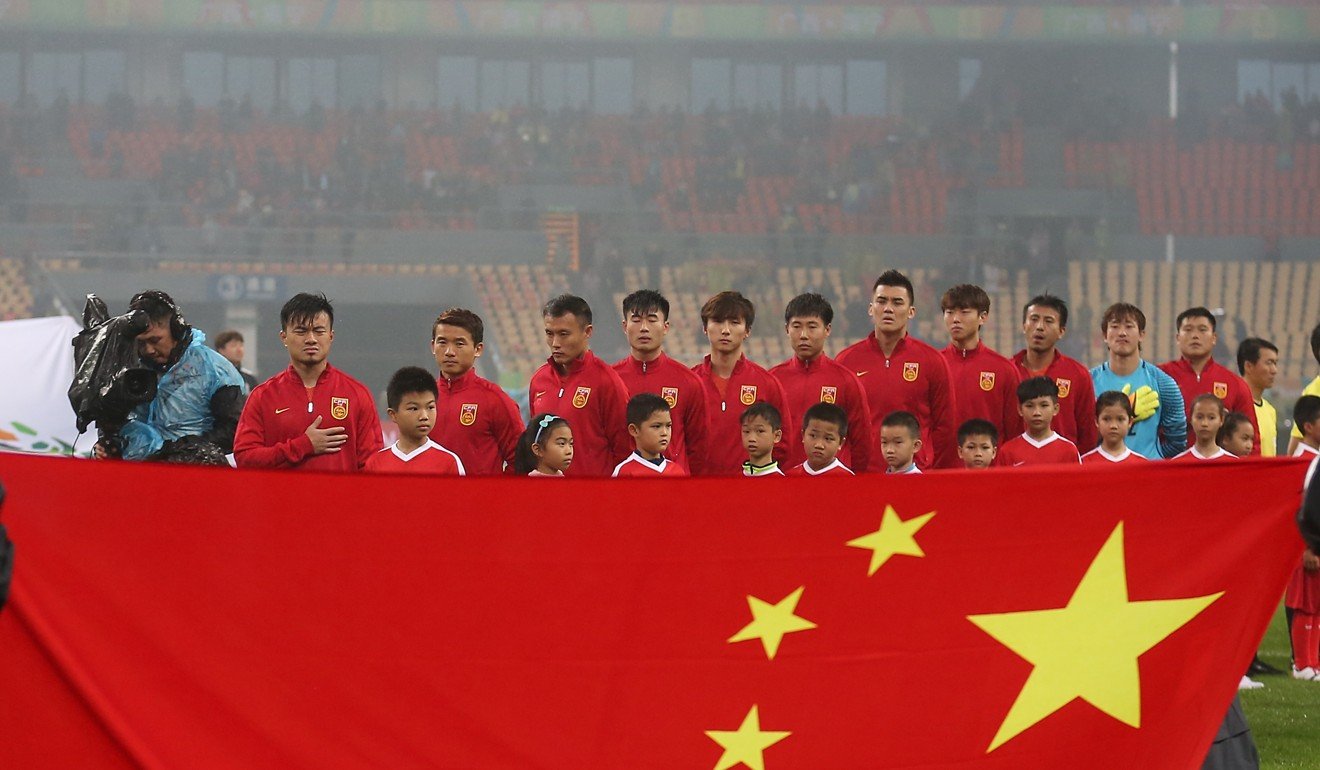

Hong Kong made headlines after hundreds of its soccer fans booed during the Chinese national anthem ahead of a World Cup qualifier between the city’s representative team and China in 2015.

Back then, the local soccer governing body was fined by international football authorities over the jeering. But such acts could soon become punishable by law in Hong Kong under proposed national anthem legislation currently making its way through the National People’s Congress, China’s top legislature.

Beijing has made known its intention to have the law applied to Hong Kong as well as the mainland, arguing it would help foster social values and promote patriotism. But Hong Kong’s opposition pro-democracy politicians expressed concerns that the law would be too wide in scope and vague enough to hamper freedom of expression and creativity. Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor has urged Hongkongers not to be overly sensitive and politicise the issue. The proposed law also comes against a backdrop of growing separatist sentiment in Hong Kong.

1. What is the national anthem law about?

A draft of the national anthem law, first proposed in June, had its second reading by the NPC Standing Committee, the executive body of the national legislature, on Monday.

The proposed law has sparked controversy over the harsh sanctions it would impose for any malicious revisions to the lyrics or derogatory performances of China’s national anthem, March of the Volunteers.

According to Chinese state media, such transgressions would be punishable by up to 15 days in detention.

Watch: How well do Hongkongers know their national anthem?

The law would place a range of restrictions on Chinese citizens. It would ban people from playing the anthem at events such as funerals or using it as background music in public places. It would bar use of the anthem in commercial advertisements, and require attendees at events to stand up straight “solemnly” when the anthem plays.

The bill also covers education, and promotion of the song. It states that the anthem should be included in primary and secondary school textbooks, and that people should be encouraged to sing it on the proper occasions to “express patriotism”

Key for Hongkongers is the prospect that the law could also be applied in the special administrative region. The Beijing News reported on Monday that the NPC Standing Committee would officially propose at its bimonthly meeting in October that the legislation be inserted into Annexe III of the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution. Annexe III lists the mainland laws that should also apply in Hong Kong.

2. Why would Beijing propose such a law?

Zhang Haiyang, deputy head of the NPC’s law committee, described the legislation as “feasible, necessary and of great significance” to foster and practise the country’s socialist core values and promote a patriotic spirit.

Shen Chunyao, head of legislative affairs for the committee, said earlier that a standard version of the anthem should be adopted, and that the new law would help stamp out improper behaviour when it is sung.

While the goals of mainland lawmakers are clear, Hong Kong politicians are split on why such a law would be proposed in the first place and extended to Hong Kong.

Wong Kwok-kin, a member of the Executive Council – the body of advisers to Hong Kong’s leader – and a member of the city’s legislature, said the rise of separatist sentiment in Hong Kong alongside insults hurled by young people at the anthem during local soccer matches were the catalysts for the law.

He was referring to an incident two years ago in which hundreds of Hong Kong soccer fans turned their backs and jeered while displaying white signs saying “boo” in English when the anthem was played at the match between the Hong Kong and China teams at the city’s Mong Kok Stadium. Both sides use the same anthem, which local fans have continued to boo when facing other teams.

Watch: Hong Kong soccer fans boo the China national anthem

But another Exco member, Ip Kwok-him, a local delegate to the NPC, disagreed. He said there was no reason for Beijing to come up with a law for Hong Kong, “a small place with a small population”.

3. How could the law extend Hong Kong, given mainland laws do not apply in the city?

Under the “one country, two systems” governing formula that guaranteed Hong Kong’s freedoms after its return to Chinese sovereignty from Britain, for a national law to take effect locally it has to be inserted into Annexe III of the Basic Law.

A number of laws were added to Annexe III and applied from the date of the handover on July 1, 1997. These were laws on the national flag, national emblem, the Chinese army and regulations concerning consular privileges and immunities.

Since the handover, two more national laws have been added – a law on the country’s exclusive economic zone in its surrounding seas and continental shelf, which was added in 1998, and legislation on judicial immunity from compulsory measures concerning the property of foreign central banks, introduced in 2005.

The mainland laws on the national flag and emblem were adapted into local laws and Carrie Lam has suggested the same would be done for the national anthem law.

4. What are the differences between the current national flag and emblem laws in Hong Kong and those on the mainland?

Hong Kong’s National Flag and National Emblem Ordinance stipulates that a person who desecrates the national flag or national emblem by publicly and wilfully burning, mutilating, scrawling on, defiling or trampling on it commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine of HK$50,000 and imprisonment for three years.

That punishment is different to the penalty laid down in Article 299 of China’s criminal law, which states that similar behaviour is punishable by up to three years’ imprisonment, criminal detention, public surveillance or deprivation of political rights.

Watch: How well do Hongkongers know their national anthem?

In a landmark ruling in 1999, Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal ruled unanimously that the National Flag and National Emblem Ordinance was constitutional.

Then chief justice Andrew Li Kwok-nang said the legislation imposed a permissible restriction on freedom of expression. He cited the symbolic role played by the flags in ensuring implementation of the “one country, two systems” concept and maintaining national unity after the handover.

The case was triggered by activists Ng Kung-siu and Lee Kin-yun, who “extensively defaced” flags in a peaceful pro-democracy demonstration in 1998.

Lawyers for Lee said the ruling was a backward step in the protection of Hongkongers’ freedoms of expression since the handover.

5. What are the concerns of Hongkongers over the anthem law?

One of the biggest worries about the proposed anthem law is that it would hamper Hongkongers’ freedom of expression and creativity with the anthem.

Noting grey areas in the legislation, songwriter Adrian Chow Pok-yin described the law as “playing with a knife above one’s head”, which would force songwriters to avoid using the anthem, regardless of their intentions, for fear of being prosecuted. It is unclear whether filmmakers would be able to use the anthem in movies.

Legislator Michael Tien Puk-sun, also an NPC delegate, said making the local laws would not be easy.

“We have to discuss in detail what behaviour is allowed and what is not. Like what if someone pronounces the Putonghua inaccurately while singing the [anthem]?” he said.

Tien said the city was obliged to bring in the laws, but that there was no need to rush it.

Questions have also been asked on how strictly the law would be enforced. Would someone who did not stand solemnly or who played with his mobile phone while the anthem was being played be deemed to be disrespectful? Civic Party lawmaker Dennis Kwok said this could create problems between police officers and the public if such vigilance was required of the law.

Watch: 5 reasons why the Chinese national anthem is the saddest ever

6. How far could Hong Kong go in amending its laws?

On Tuesday, Lam said the city should enact the national anthem law by passing its own legislation suited to local needs . Pan-democrat legislators have called for this move to protect the rights and freedoms of Hongkongers.

Kwok, a barrister by trade, said a local law was a must, as many of the requirements of the mainland legislation would not be applicable to Hong Kong, such as the punishment of 15 days in detention. It would also help define the scope of the legislation by clearing any grey areas, he said.

Speaking on a radio show on Tuesday, Paul Lam Ting-kwok, chairman of the Bar Association, which regulates barristers, said a lot of technical problems would emerge should the mainland’s national anthem law be automatically implemented in Hong Kong.

The government should conduct a thorough public consultation before putting forward a local bill, he said, in a bid to make sure it would not pose unreasonable restrictions to freedom of expression.

And he said the new law should not be retroactive.

Professor Albert Chen Hung-yee, a legal scholar at the University of Hong Kong and a member of the Basic Law Committee, that advises Beijing on Hong Kong’s constitutional future, said the sections in the national law prescribing penalties could be adapted to fit Hong Kong’s legal system, as happened with the flag laws.

Additional reporting by Kimmy Chung