Extradition bill crisis: Why are the young people of Hong Kong angry and deeply unhappy?

- Devastating scenes of vandalism at the city’s legislature have shocked the world and exposed the despair and desperation of Hong Kong’s youth

- Adults care about their jobs and flats but kids only think of right and wrong, with a pure heart, one online commentator says

Inside the still gleaming new-age Legislative Council complex in Tamar, built only eight years ago, the youngsters used the bright white walls to share their feelings with the world.

In the dim light, words such as “dog officials”, “freedom” and “Hong Kong is not China – not yet” appeared almost instantaneously as they shook spray paint cans and scrawled out Chinese characters, interspersed with lines in English.

It was July 1, the day to mark the 22nd anniversary of the city’s return to Chinese rule.

The protesters, who had stormed the building after eight hours of besieging it, also defaced the city’s emblem on the main wall of the chamber, smashed equipment and installations, including the portraits of the three post handover presidents of the legislature.

A group of around 10 diehards apparently even had a “bring it on” mentality. They were ready, according to police sources, to sacrifice themselves to draw global attention to their cause in demanding the complete withdrawal of the shelved extradition bill.

Many later told the media they felt guilty at the three sudden deaths that appeared to be related to the bill. “To those three”, one of the messages painted in black read. That number would later rise to four. What was it about the bill, which would have allowed the transfer of fugitives to mainland China and other jurisdictions which the city does not have a deal with, that sparked the protests and the destruction of the chamber?

The devastating scenes of vandalism shocked the world and exposed the darker side of Hong Kong’s social movement. Even as they did not condone the violence, to many, it spoke of the despair and desperation of the city’s youth.

As questions were being asked about what was troubling young people, it seemed such bitter irony that two years ago, embattled leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor had placed them front and centre of her campaign to be elected as chief executive. She had pledged “We Connect” to the youths of the city, who, as events of the past weeks have shown, could not be more disconnected from her government.

She had unveiled ambitious initiatives, such as elevating the 28-year-old Commission on Youth to become the new Youth Development Commission, to be chaired by Chief Secretary Matthew Cheung Kin-chung and revamped the Central Policy Unit to attract young people.

Far from feeling empowered by such measures, it would appear the extradition bill was the proverbial straw that broke young people’s back.

“The extradition bill was a trigger point,” said Samuel Chu, an 18-year-old secondary school student who has been a regular first aid volunteer on the frontline of protests. “The government has never really listened nor responded to our calls.”

Economic grievances

Three days after the dreadful break-in, someone started a thread on the popular Reddit-like online forum LIHKG: What are the reasons behind young people’s determination to join the anti-bill movement despite the high stakes?

“The adults have too much calculation on their interest. They care about their jobs and their flats; they plan to move out once they earn enough and worry about being barred from running in elections in future if they are involved in clashes. But kids have less to worry about – they only think of right and wrong, with a pure heart,” said a comment, which got the most endorsements.

Others painted a gloomy picture of a future in the city they were born in: “Poor working conditions, no flat, no democracy – everything that appears ordinary in other countries is absent in Hong Kong.”

Against the backdrop of stagnant social mobility, soaring property prices and widespread youth discontent, Lam spelled out six ambitious goals for her five-year term in her 2017 maiden address: encouraging youth participation in politics, public policy discussion and debate, and addressing their concerns about education, careers and home ownership.

While the city’s unemployment rate has been low generally, at 2.8 per cent in the first quarter of this year, the rate among youths is noticeably higher.

Almost 7 per cent of those aged between 20 and 24 who are not in school – or 16,700 people – are unemployed, while the figure for those aged 25 to 29 was 3.9 per cent.

Similarly, the rate of joblessness among those with only postsecondary diploma or certificate was 4.1 per cent; those with associate degrees was 3.5 per cent, or about 9,000 people.

Hong Kong has also set world records in home prices and has a glaring income gap. In 2016, it had a Gini coefficient – a measure of inequality – of 0.539, which Oxfam said was the highest in 45 years.

“Some young people really see no future in Hong Kong,” said Naomi Ho Sze-wai, a 25-year-old social worker and organiser at the group Youth Policy Advocators.

While there is no study on the demographic of the protesters, observations on the ground suggest those who took went beyond the weekly marches to join other actions – such as the consulate runs and sit-ins outside the legislature – were mostly tertiary students and working class youngsters with flexible job hours, working as waiters, drivers and logistics workers. The profile was different from the weekend marches, with its more diverse mix of age groups.

But Education University chair professor Stephen Chiu Wing-kai, who has been researching on the city’s youth, warned the roots of young people’s unhappiness should not be traced solely to the lack of economic empowerment as their disenfranchisement was on so many levels.

Pro-establishment politicians, he said, had been labelling the young participants of the 2014 Occupy movement as losers with no future.

“The young people’s resentment … does not stem from the anxiety over their personal lives but more from their pursuit of universal values and their distrust of the local and central government,” Chiu wrote in a recent Chinese newspaper commentary, citing his previous research.

Unpopular mother

Hours before violent clashes broke out between protesters and police outside the legislature on June 12, Lam had explained in a TV interview why she could not be cavalier about withdrawing the bill.

“To use a metaphor, I’m a mother too, I have two sons,” she said. “If I let him have his way every time my son acted like that, such as when he didn’t want to study, things might be OK between us in the short term.

“But if I indulge his wayward behaviour, he might regret it when he grows up.”

She eventually suspended the bill days later, but refused to withdraw it even after a peaceful march which drew an estimated 2 million people and sparked the violent siege of July 1.

Lam only declared the bill “dead” this week even as she dismissed the protesters’ other demands, such as ordering an inquiry into the police’s handling of the violent clashes on June 12.

Critics said Lam’s view of her role over the city as that of a strict mother was insulting to young people who want to be seen as adults with a full say on the fate of the place they call home. Indeed, a Cantonese expletive of how “Carrie Lam is not my mother” has become one of the oft-chanted slogans in the marches.

That same top-down approach appears to have been applied to Lam’s initiatives.

One scheme rolled out over the past two years is the Pilot Member Self-recommendation Scheme for Youth, which allows young people to offer their names to the commission and various advisory committees.

The government also set up a high-level Policy Innovation and Coordination Office (Pico) to replace the Central Policy Unit, dangling pay packets of up to HK$95,000 for young people when the median income for 25 to 34-year-olds is only HK$15,000, according to the 2016 by-census.

“These initiatives, to me, are all political shows,” said fifth former Chu. He had attended seminars held by the commission ostensibly for officials to discuss policy issues with young people.

“A lot of us fired questions at them, but they barely directly addressed them.”

A 24-year-old nursing student who only wanted to be known as Jas agreed, as she recounted her experience in applying under the self-recommendation scheme.

“It is very hard to get in and it appears to me there is a hidden rule … they are looking for someone obedient,” she said. “There’s too much censorship.”

Isaac Pang, a 18-year-old student at the HKU SPACE community college, was more dismissive as he called the scheme a platform “for people to build up their CV”.

One of the three young members selected from 503 applicants to the commission was an opponent of the pro-democracy Occupy movement in 2014.

While Lam had refurbished the Pico office with an open plan similar to layouts at tech companies, a person familiar with its operations lamented that the new agency had limited impact. One of the major constraints, he said, was the office had no policy jurisdiction.

“Youth policy, after all, is under the purview of Home Affairs Bureau. No one has yet to sort out how to reconcile the role of Pico with the bureau,” the source said. “The roles, division of labour and strategies are all unclear.”

Mending the rift

On Tuesday, Lam vowed to improve the government’s public consultation exercise and revamp the Youth Development Commission, so it could become a “true platform” for young people’s views. She did not elaborate but few were holding their breath.

Moreover, even the commission’s vice-chairman Lau Ming-wai, the son of property tycoon Joseph Lau Luen-hung, had suggested the extradition bill could not have plumbed the depths of anger in the city if the protesters had not won cross-generational support.

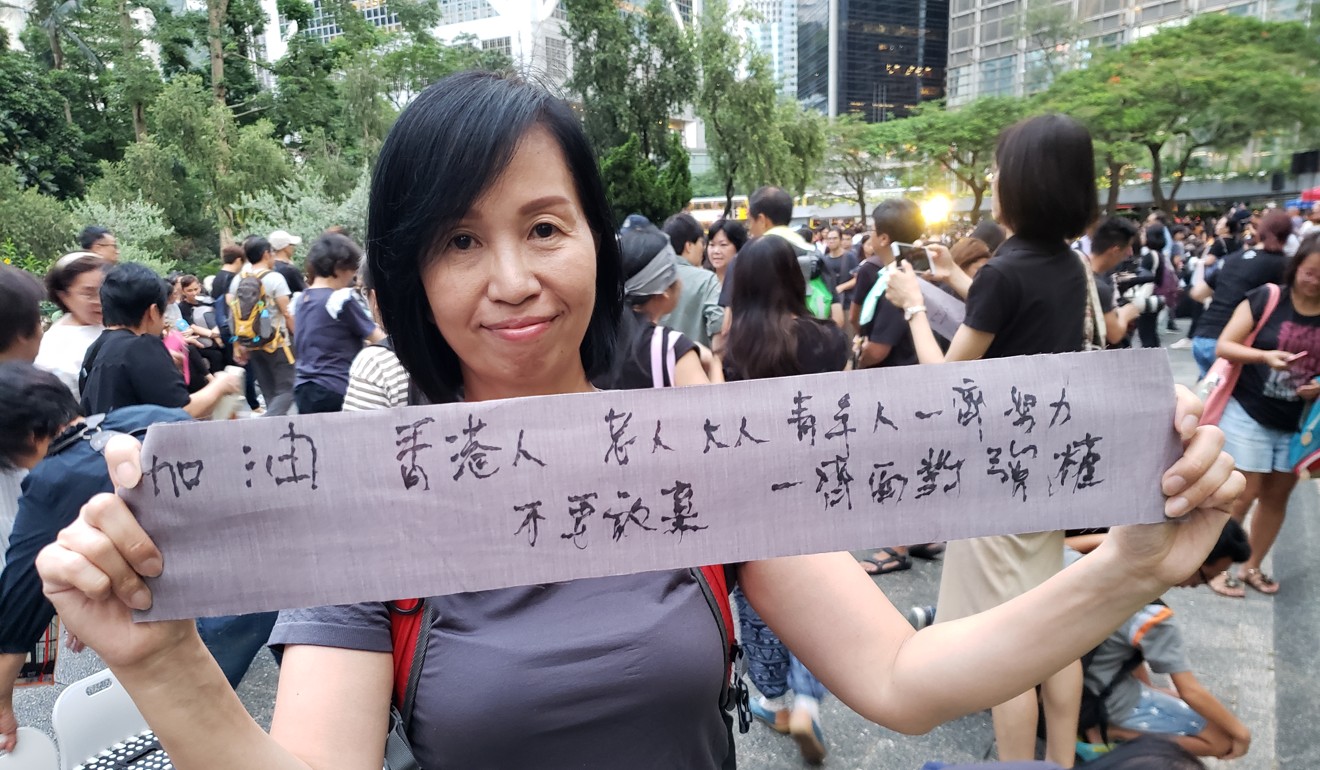

Following the Legco break-in, hundreds of mothers gathered for a second night rally to voice their support.

Some felt guilty seeing young people risking their future and not doing enough to fight for their rights, while some others expressed understanding of their turning to violence.

“Young people, you did not do anything wrong. You only did what we dared not to do and did more than we expected,” said Kwan Tsui-tsui, who is 64 with three grown-up children. “We Hongkongers should thank you.”

Rachel Lau, whose 26-year-old son was among the protesters outside Legco on July 1 but not involved in the breach, said she would have supported his decision if he had joined the storming.

“I can understand why they did it,” Lau said, blaming the government’s uncompromising stance.

“The responsibility lies with the government, not the youngsters.”

Former environment undersecretary Christine Loh Kung-wai said the city needed a months-long open community dialogue – similar to that of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission set up in South Africa following the end of apartheid – to heal the wounds in the wake of the political crisis.

When Lam’s second offer for a meeting was snubbed again by student leaders earlier this week, Loh said what society needed now was a listening session, not a debate.

“A debate would only become a political show as all sides would only reassert their position”, Loh, the co-founder of think tank Civic Exchange, said.

“We have to listen to people who disagree with us. There are truths on all sides.”

She proposed universities organise such dialogues – which would allow people to vent their frustrations and even anger – and getting a team of experts specialising in conflict resolution on board to identify best practices.

“We have to accept these dialogues will not stop the protests immediately,” Loh said. “But we need this process.”

Social worker Ho called for reforming the Youth Development Commission into an elected body, as she slammed the current appointees as mostly “bigwigs, middle-aged men and women who already have preconceived views”.

A check of the commission papers suggests the task force – under the helm of the No 2 official – had given significant focus on promoting the Greater Bay Area initiative among youth since its launch, parroting the government’s agenda rather than focusing on young people’s more urgent concerns.

Ho argued the task force should be given the power to discuss their proposals in district councils or even the legislature, so the voice of young people could really be heard.

But to student Chu, all of these reforms could still not mask the inconvenient truth that Hong Kong did not have democracy.

“The power of the administration should come from the people,” he said. “We should be allowed to elect our own leader and lawmakers or else it will be difficult to get our voices heard.”

Even before that happened – a wish denied them in 2014 when Beijing came up with an electoral framework that pre-vetted potential chief executive candidates – young people were being blocked from having political representation.

The impact of the disqualification of election hopefuls on the grounds of their political views or conduct in Legco was coming home to roost. Chu said these moves might have made the government look strong to Beijing but they caused young people to lose heart.

“I do not support independence, but I think the matter should be open for discussion,” he said.

Being part of the dramatic ups and downs of the past few weeks, Jas believed she was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. She knew one of the four people who died in the midst of the crisis.

Her heart ached, she said, sensing the deepening rift in society. She found herself breaking into tears easily and losing the desire to even handle simple daily chores. It was only recently she sought counselling.

Jas wanted to reassure the government the protesters were not their enemies. They did what they did out of love for the city they called home, she said.

“Most of the protesters are in fact from the lower class who have no other way out, unlike those richer people who could leave the city anytime,” she said, recalling what she saw at the protest sites.

“We are all only trying to protect our place, the best way we know how.” That sentiment might have been lost in the angry scrawls of that night of reckoning in Legco and the protesters too admitted they knew the world would soon move on to the next big story.

The question still unanswered, however, is whether the government will get the right message.

Additional reporting by Su Xinqi