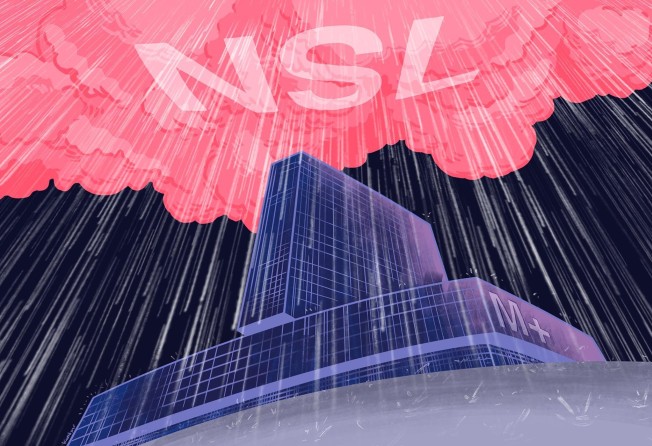

Political storm raises stakes for Hong Kong museum M+ and its lofty ambition to be among world’s best

- Fresh attacks pile pressure on curators preparing to unveil impressive collection of Chinese art

- Observers say museum has room to do its work, but must be mindful of new political realities

This is the second of a two-part special examining the debate around the flagship of the Kowloon arts hub and what it means for Hong Kong. The first report can be found here.

From its initial conception, M+ suffered from confusion over what it is supposed to be.

Caught in a political storm over works of art just months before its grand opening later this year, the new art museum in the West Kowloon Cultural District (WKCD) was not initially conceived as a specifically Hong Kong establishment.

For years after the government mooted the idea of a cultural district in West Kowloon in 1998, the plan was to get a renowned museum from Europe or the United States to open a Hong Kong branch with a ready-made collection, expertise and international name recognition.

As late as 2005, a consortium formed by Cheung Kong and Sun Hung Kai Properties, two developers bidding to build the WKCD, was in talks with the Guggenheim Museum in the US and the Centre Pompidou in France.

The then director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in New York told The New York Times at the time that the Guggenheim was interested in opening in Hong Kong because the city “needs a world-class museum”.

His remark reflected a widely held belief at the time that Hong Kong was simply not capable of building such a museum itself.

“It was different back then,” said jewellery designer Kai-yin Lo, one of the longest-serving advisers to the government on the WKCD development. “Nobody in Hong Kong had ever tried to build a museum outside the government system and only officials ran museums. We were looking for a new point of view.”

When the government invited proposals to develop the 40-hectare harbourfront district in 2003, the tender stated that it would include a cluster of four museums for moving images, modern and contemporary art, ink art and design.

Three years later, the government scrapped the tender, following public outcry over handing the whole project to property developers and disagreements with developers on basic issues, including the government’s insistence on having a canopy over part of the district.

Veteran Hong Kong art critic John Batten recalled: “It was a moment of crisis and the government didn’t know how to progress. So the government invited many people from the arts community to suggest what to do next.”

Batten submitted a proposal on behalf of the International Association of Art Critics in 2006, urging the government to drop the idea of four themed museums and go with a single anchor museum of contemporary culture funded by the WKCD Authority.

That was what the government opted for, resulting in the M+ museum opening later this year. In late 2016, however, authorities announced the addition of the Hong Kong Palace Museum to the district.

The idea of a contemporary museum with an independent Asian perspective, loosely modelled on the Centre Pompidou in Paris, remains a bold one. M+ will showcase art, moving images, design and architecture.

Its collection will be focused on Hong Kong and its immediate neighbours. Hong Kong art currently makes up about a quarter of its collection.

The minimalist moniker M+ was chosen to show that this was a museum and much more.

“We wanted a name that encompassed different aspects of culture today, and culture in the future. We wanted a name that was elastic,” said Lo, an M+ board member who was on the naming panel.

‘M+ at the front line of culture wars’

After long delays and cost overruns, M+ is finally on track to open at the end of this year. But the “elasticity” of its nature means that an ongoing debate over what the attraction ought to be continues unabated. The museum’s interests in design and cutting edge art practices saw it acquiring a sushi bar in Tokyo and the entire body of digital art made by a pair of South Korean artists.

Predictably, these have been Hong Kong’s own “shark preserved in formaldehyde” moments. As they did with that famous work by British artist Damien Hirst, people have kept asking repeatedly, just how is that art?

Last month, in the wake of major changes in Hong Kong’s political landscape, came fresh attacks on its collection and curatorial independence, with pressure to remove artworks considered critical of China.

Pro-Beijing figures have even demanded the resignation of museum director Suhanya Raffel for saying during a media tour last month there would be “no problem” going ahead with plans to show works by dissident artist Ai Weiwei and images referencing the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown on pro-democracy protests in Beijing.

The remarks by Raffel, who took up her post in 2016 after a run as deputy chief of the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, sparked a storm of protests over M+ artworks that might run afoul of the national security law introduced last June.

The stakes are high. The WKCDA has set M+ the target of being the first museum of its kind in Asia and to be ranked among the top five museums in the world for visual culture. This is in line with Beijing’s 14th five-year plan that identifies Hong Kong as a bridge for arts and cultural exchanges between the nation and the world.

The museum is on the front line of culture wars in Hong Kong

To achieve such lofty ambitions, M+ needs international credibility. But given growing ideological tensions between China and the West, it is going to be hard for the museum to meet the expectations of its political master as well as an international art world based on the values of liberal democracies, said Professor Paul Gladston, an expert on Chinese art and its relationship with geopolitics.

“M+ should be encouraging critical thought at the very least, since that is something the liberal and progressive international art world expects museums to fulfil,” he said.

“But given the local political realities, M+ curators will also need to avoid being seen to challenge what the Chinese government considers to be politically acceptable too flagrantly, or M+ may find itself subject to direct government censorship.”

A professor of contemporary art at the University of New South Wales, Gladston added the national security law had put added pressure on the new museum and he was not surprised by the political row over its artworks.

“The museum is on the front line of culture wars in Hong Kong, pitching those supportive of the authority of Beijing against the more liberal politics of many people in the region. The museum is caught between those outlooks and subject to both,” he said.

Law provides protection for curators

Those who have attacked M+ over the past month have hit out not only at works considered politically subversive, such as Ai’s Study of Perspective – Tian’anmen (1997), but also images associated with liberal, Western values such as those containing nudity or portraying homosexuality.

Many of these works are from a unique and extensive collection of Chinese contemporary art from around 1970 to 2010 collected by Swiss businessman Uli Sigg and part-gifted and part-sold to M+ in 2012.

Sigg has said he chose to send the 1,510 works to Hong Kong because he wanted them shown to the public within the country, and because there was more freedom of speech in Hong Kong than on mainland China.

The recent hullabaloo prompted Mathias Woo Yan-wai, executive director of theatre group Zuni Icosahedron, to join the fray. In an article in last week’s issue of Chinese-language weekly Yazhou Zhoukan, Woo, a long-term critic of the lack of local senior management and Hong Kong focus at WKCD said the Sigg collection should never have become a Hong Kong museum highlight.

“Was the real reason for introducing these works into M+ to encourage anti-China sentiments in Hong Kong?” he asked.

Woo, a fierce critic of what he called “Westernisation” went on to suggest that as both the Art Basel, which holds Asia’s largest contemporary art fair in Hong Kong, and Sigg were both Swiss, M+ was essentially helping to raise the value of “Swiss Western contemporary art collections”.

M+ curators thus far have not been cowed into submission, back then and now. Led by Sigg Senior Curator Pi Li, they did not pull back from showing artworks with political themes when they put on a public preview of the collection in 2016.

It included photographs by photojournalist Liu Heung-shing taken on June 4, 1989 in Beijing, the day the Chinese government ordered a military crackdown on protesting students at Tiananmen Square.

There was no criticism of the artworks then. In fact, the selection was praised by art historians as a thorough introduction to the art and history of an important chapter in China.

Current concerns over the national security law and the hostility of pro-Beijing politicians have raised questions about what, and how much, will now change at M+.

Despite the controversy, Raffel and her team can take some comfort that structures are in place to protect curatorial independence at the museum.

For example, the WKCDA Ordinance states that the authority in charge of the cultural district must “uphold and encourage freedom of artistic expression and creativity”. It also states the authority is not obliged to act on directions by the city leader if they are wholly or partly inconsistent with the ordinance.

Also, in 2016, the museum was incorporated as a wholly owned subsidiary of the WKCDA, with an independent board.

According to art critic Batten, WKCDA board members mostly have a business background and are unfamiliar with the visual arts scene, whereas M+ board members tend to know contemporary art.

Having its own board meant the museum could ensure that independent discussions about art could happen without having to be sidetracked by other WKCD issues, he said.

‘An absolutely invaluable contribution’

Mainland Chinese curators say they have observed greater censorship of the arts since President Xi Jinping came to power. Despite Beijing’s tightening grip over Hong Kong, the city’s relative freedom and the independence enjoyed by M+ give it a special role as a platform for studying the country’s contemporary culture.

Guangzhou-born art critic and curator Hou Hanru, now living in France, said M+ should give the public access to a wide range of works so people could debate with art professionals and make up their own minds.

“I don’t always agree with Ai Weiwei’s works. Sometimes I can be quite critical, but I will definitely defend the right to present his work as well as all other artists’ works,” he said, adding the Sigg Collection was one of the most important collections of Chinese art.

The Swiss businessman lived in China for many years and was his country’s ambassador to Beijing between 1995 and 1999. He amassed his art collection well ahead of other collectors and institutions.

His collection is considered the most representative of a transformative period in Chinese history, and he has said that he aimed all along for an “encyclopedic documentation” rather than a collection based on his personal tastes.

Hou said: “His donation is an absolutely invaluable contribution to the making of M+.”

Some of the best-known works in the collection are from the 1990s “cynical realism” movement, a reaction against the “socialist realism” used as propaganda by the Communist Party.

Even today, works by artists portraying cynical representations of Mao Zedong and other state symbols are known to be banned on the mainland, with the authorities heeding Xi’s 2014 directive that art must project a positive image of the country and promote patriotism.

The fact that M+ is founded on a Westerner’s choice of Chinese art and is not showing the kind of “red art” favoured by the party could open it to criticism that it only represents Western values.

A museum associated with Western values could be perceived as a neo-imperial imposition on Chinese society, Gladston noted.

Progressive curators on the mainland have had decades of experience in dodging censorship, though there does not seem to be a template Hong Kong can borrow.

Most mainland institutions say they proceed on a case-by-case basis, often adopting strategies such as putting sensitive works in less prominent positions.

Contemporary art cannot be judged by the here and now

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a curator of a private contemporary art institution said the key was to stay below the radar. But the curator said there was no example on the mainland of an institution targeting the public with major exhibitions of works directly critical of the authorities.

Singapore, whose government shares similar ambitions to be an international arts hub, is also a place where the liberal values of the arts rub against political censorship and social conservatism.

Ong Keng Sen, founder of theatre company T:>Works and a former director of the Singapore International Festival of Arts, said his approach was to encourage change quietly, with an eye on the long term.

“What it means is that we slowly effect change and we do not focus too much on individual shows. Instead, we engage in long-term processes such as building alliances and solidarities, and breaking down silos,” he said.

The arts played a crucial role of “care and repair”, he added, offering a more human and intimate space that looked beyond national, official narratives.

Janet Fong Man-yee, an independent curator and academic with a focus on museum practices, said the furore over M+ showed how people had different expectations of the work of curators.

“When I curate an exhibition, I do it for the future. Contemporary art cannot be judged by the here and now. My role is to lay out what artists are saying today, archive them and let future generations decide,” she said.

Gladston said M+ would have to be inventive in the face of tightening controls by Beijing over Hong Kong.

“If the directors of M+ are smart enough, they’ll be able to sustain the museum as a focus for critical public discourse, albeit in ways that are more oblique than they and international onlookers might ideally wish for,” he said.

“If they aren’t so nimble? … Well, let’s see what happens.”