Who defines ‘fake news’ in Hong Kong, and is a law needed? Calls for legislation spark fears of curbs on media, critics

- City leader Carrie Lam has promised new legislation while police chief calls for more control, but an expert suggests education could be the answer instead

- New laws elsewhere, including Singapore, are controversial for targeting critics and opposition

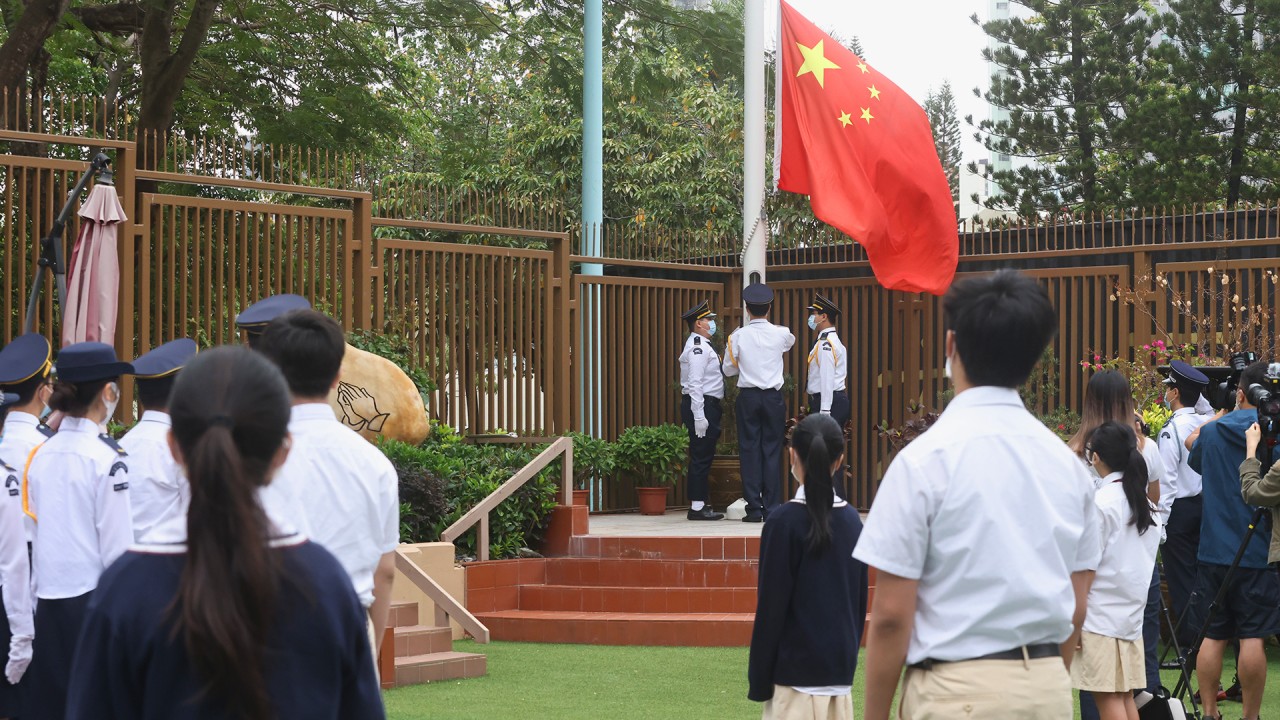

When a photograph of a Hong Kong schoolgirl pointing a toy gun at her classmate during the city’s first National Security Education Day was shared widely online recently, few imagined it would spark calls for a new law against “fake news”.

Apple Daily put the photo on its front page on April 16, juxtaposed against an image from 2019 showing a controversial police operation during anti-government unrest, when officers stormed an MTR train compartment in pursuit of protesters.

Police chief Chris Tang Ping-keung accused the newspaper of “inciting hatred” and declared that he would back a new law banning fake news.

All at once, it appeared that Hong Kong could be the next place in Asia after Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines and Thailand to have a law against fake news or misleading information.

But leading scholars talking to the Post warned that such a law may further dampen free speech and press freedom in Hong Kong, as examples from those Southeast Asian countries showed the legislation was introduced when governments were under increased political pressure and could be used to crack down on political opponents and activists.

While the Hong Kong government has not spelled out what it has in mind, pro-establishment legislator Priscilla Leung Mei-fun, a member of the Basic Law Committee, said she supported a law that regulates “malicious publishing”.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor first mooted having a fake news law in February, when she vowed to introduce new legislation to combat the spread of misinformation, a trend she said had increased during the protests in 2019 and the coronavirus pandemic.

During the 2019 civil unrest, both opposition and pro-Beijing camps resorted to using half-truths, carefully edited video, and selective reporting to sway followers on social media.

At the start of the Covid-19 outbreak last year, Hong Kong was gripped by rumours of impending shortages of essentials, which sent residents into a panic-buying frenzy – a situation also seen in other countries.

The government also regularly publishes statements to clarify its position, while press officers follow up with media organisations for corrections and clarifications of published errors.

Conceding it would be difficult to draw up a complete legislative proposal in a short time, Lam said her administration wanted to deal first with issues such as restricting doxxing activities.

Demands for a fake news law escalated again recently when pro-Beijing media supported Tang’s attacks on Apple Daily, and pro-establishment lawmakers renewed their calls too.

Expressing concern in an open letter to Tang on Thursday, the Foreign Correspondents’ Club asked the police chief how he defined “fake news”.

“The term ‘fake news’ is vague, subjective and has been used by public figures around the world to attack coverage they view as unfavourable – and the journalists responsible for it – even when it is factually correct,” it said, reflecting fears that the proposed law would be used to suppress press freedom.

Communications and legal scholars warned that fake news laws have proven controversial elsewhere, while journalist unions urged the government not to misuse new laws to curtail press freedom.

Dr Lasse Schuldt, an assistant law professor in Bangkok’s Thammasat University who has studied fake news laws in Asia, said such laws had often been introduced at times when governments faced increased political pressure.

The German academic has researched and written about different fake news laws in Asia, and how they relate to fear, freedom and public interest in countries such as Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand.

Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act 2019 (POFMA) became law in October 2019. It allows any minister to decide what constitutes a “false statement of fact” and initiate actions – such as requiring online media platforms, including social media sites like Facebook and Twitter, to carry corrections or remove the offending content.

Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has defended the law as a step forward in fighting online falsehoods.

But Schuldt noted that POFMA was introduced ahead of Singapore’s general election last July and the city state’s brief campaign period saw a string of POFMA-related correction directions addressed at government critics and opposition parties.

Malaysia enacted its Anti-Fake News Act in 2018, at a time when former prime minister Najib Razak faced serious allegations of corruption. The controversial law, described by some as an attempt to quell unwelcome reports, was repealed in late 2019.

Then, in March this year, the Malaysian government issued an Emergency Ordinance which was regarded as “an aggravated reincarnation” of the earlier law as it included several provisions that set aside regular legal guarantees.

In the Philippines, the Bayanihan Act outlaws eight acts including spreading fake and alarming information.

It was introduced early last year when the Philippine government was under increasing attack for its poor handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. The administration itself was criticised for being a source of misinformation for years.

“The enactment of anti-fake news laws always needs to be seen in the respective political context,” Schuldt told the Post. “Governments in Southeast Asia argued for the enactment of such laws to protect the electoral system against foreign interference and, as in the case of Singapore, the peaceful coexistence of diverse groups in society.”

In defining “fake news” or “false information”, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand, all criminalised the dissemination of false information. Singapore and Thailand include misleading information under this category as well.

Schuldt said all these countries highlighted “intention” behind the offending action, which meant the person spreading the information must know it was false or misleading.

In terms of the impact of fake news, most laws were concerned with national security and public order, and whether the fake news posed security threats, according to him.

‘Let courts decide who is guilty’

Lawmaker Priscilla Leung, who is also a barrister, said that unlike Singapore, Hong Kong could have an anti-fake news law with clear definitions.

“Prosecutors will have to prove that the person knew it was unverified information, but still proceeded to publish it maliciously,” she said.

“If a media organisation, for example, can prove that it did due diligence and did not publish any malicious information to incite hatred or violence, I believe the new law would not dampen press freedom.”

She said including the word “malicious” in the law would require a high threshold of proof.

Instead of allowing the government or ministers to initiate action, as in Singapore, Leung suggested that only the court should be allowed to rule if a person or organisation is spreading misleading information or fake news.

Schuldt said the effect of anti-fake news laws on individual rights would eventually depend on the interpretation and level of enforcement by authorities and the courts.

“In Southeast Asian countries where authorities and courts already tend to interpret national security laws largely in favour of state interests rather than individual freedoms, the fake news laws certainly resulted in additional restrictions on free speech and press freedom,” he added. “Fake news laws can become another tool in the authoritarian toolbox.”

Masato Kajimoto, a journalism professor at the University of Hong Kong who studies misinformation, said misinformation could be extremely damaging to society, especially when people believed the falsehood and took action.

But he also said Hong Kong’s existing legal frameworks, including its libel laws, were enough to deal with bogus claims without the need for a new “fake news” law.

The Japanese scholar added that current internet advertising models needed regulating more than people’s speech.

“Financial incentive is a big factor for misinformation to be created and disseminated, and curtailing that in the misinformation ecosystem would reduce the amount of nonsense news we come across every day,” he said.

“But there is no quick fix for the issues surrounding misinformation. They can only be solved by societal efforts, not by the authorities,” he said. “I believe education is the answer. We need to nurture discerning news consumers who can tell fact from fiction, identify quality journalism, and fact-check questionable content.”

Kajimato noted it was hard to define what constituted “fake news”.

“Without clear definitions, such regulations could be used as a catch-all tool to suppress opposing views and unflattering descriptions by the authorities. We have seen that happening in some Asian countries and certainly, it will be a concern in Hong Kong too,” he added.

Chris Yeung Kin-hing, chairman of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, said the group had always opposed the idea of a fake news law, which he said had been used by many regimes to crack down on dissidents.

When disputes over media reports arose, he said, police should state which law had been violated. He added that the public, not police, were best placed to judge whether the media had handled a piece of news correctly and well.

Apart from this new proposal for an anti-fake news law, media groups earlier expressed concern that press freedom would be undermined as the government had proposed restricting public access to some data at the Companies Registry, which would be a hurdle to investigative reporting.

Departments in charge of several government search platforms – providing details of vehicle and company ownership, as well as marital status – have also modified their declaration requirements in recent years in ways observers say could expose journalists to legal risks.

The practice of searching public databases for information came into focus after the arrest and prosecution of veteran investigative reporter Bao Choy Yuk-ling last November.

A freelance producer with public broadcaster RTHK, Choy, 37, searched for some car owners’ details for a documentary that was critical of how police handled a mob attack at a railway station during 2019’s anti-government unrest.

She was convicted of providing false statements and fined HK$6,000 (US$773) on Thursday.