How a pet dog inspired a course at the Chinese University of Hong Kong: author Chan Ka-ming is out to educate on animal welfare

- Lecturer took home a new friend in 1998 – little did he know it would spark a new direction in his career towards animal welfare advocacy

“I wouldn’t have been able to talk to you about her a year ago,” author Chan Ka-ming says of his dog Bungy that died two years ago.

Eyes fixed on a page in one of his books bearing the animal’s picture, he adds: “I was deeply lost in her death.”

The cultural studies scholar first took home the miniature pinscher from a pet shop in Sai Wan Ho in 1998. Little did he know his love for the dog would spur a deep commitment to animal rights that has seen him explore ecology, human-pet relationships, the media’s representation of animals, and even philosophical debates about their place in the world.

Chan says he treated Bungy like a daughter. “I was heartbroken when she got sick,” he says.

In 2010 he started noticing the dog groaning day and night. He turned to the internet to find out what was wrong, but became distracted by stories and images of cruelty and abuse towards animals.

Brutal killings of cats and the mass slaughter of dogs for food were among a number of gruesome issues he confronted online. Feeling angry and concerned, he vowed to take his love of animals beyond simply caring for his own pet.

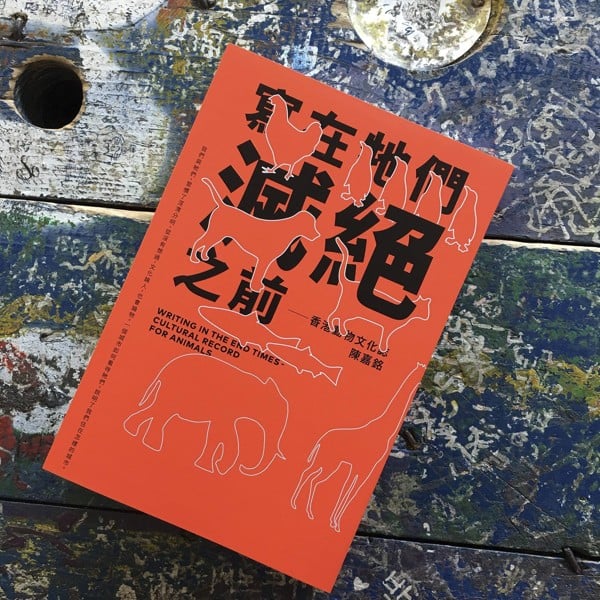

Chan began writing articles which later became parts of a newly released book titled Writing in the End Times – Cultural Record for Animals. Some of the pieces were published in local newspapers.

Covering a variety of topics, from cultural studies on animals to creatures in the media, the book highlights the need for people to recognise the social, cultural and political dimensions of the animal kingdom.

“As reflected by the name of the book, our urban and capitalist development in the world is incorrigible, and animals and ecology may be fated to disappear,” he says. “What we humans can therefore do is recognise the problem and be good to the environment and other life forms.”

Animal welfare is a topic of fast widening understanding in Hong Kong as more families welcome pets.

About 289,000 households had at least one, not including fish, between mid-2015 and mid-2016, according to a study commissioned by the Veterinary Surgeons Board last year. The number of pet dogs and cats rose from about 297,000 in 2005 to 511,000 in 2016.

But abuse remains a big problem. Two men were sentenced to 16 months in prison in 2014 for brutally kicking a cat to death – at that time the heaviest penalty ever handed down for such a crime.

Under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Ordinance, any person who cruelly kicks an animal can be fined up to HK$200,000 (US$25,600) and jailed for up to three years.

The case, says Chan, signalled a turning point in Hong Kong’s animal protection work, and the media have since started paying greater attention. It got him thinking about the roots of the problem.

For Chan, protection and punishment alone will not properly address animal welfare issues.

“Penalties are not the solution. Education is,” he says.

“It should be about culture, society and even the media. That’s the reason I wrote a lot of articles in the past. I just expanded the discussion of animal and ecology to other fields. It is not only about biology, but also social science, sociology and cultural studies.”

He has taken the responsibility for education partly on himself. As a lecturer with a PhD in cultural studies, Chan organised a new course in 2015 at the Chinese University of Hong Kong titled Animals and Society. It was the first of its kind in the city.

“I think it is very important because in Europe and the United States, there are courses related to animals as a humanities subject, from the perspective of culture and society. But in Hong Kong we didn’t have any relevant courses,” he says.

“I’m trying to show students that their eating habits are not just about the food. They are about the industry. When we talk about pets, it needs to be not only about animals at home but also the power hierarchy.

“I can’t tell you how to change the world. But at least I can open a window for you to explore related topics. And if you want to do more, you can make changes bit by bit. It’s not about ‘changing the world’ – that’s a big term.”

Chan is proud of what he has achieved, but harbours worries. Though more animal protection groups have sprung up in Hong Kong, they sometimes find themselves in conflict with one another due to differences in their methods or ideologies, despite a common objective, Chan says.

He called on the groups to coordinate and cooperate instead of point figures.

“It is not a good way to deal with social issues,” he says.

The environmental impact of expanding urban development in the city is another concern.

“Nature and the environment are deteriorating because the logic of urban development is simple-minded,” he says.

The government’s strategy of developing more housing without due consideration for quality or planning has left less space for animals, Chan argues.

“This is contradictory because animals are then left with insufficient space in country parks, and are forced to come into the city, including boar and cattle. The public then call that an ‘invasion’,” he says.

Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor announced in her policy speech in October plans for a 1,700 hectare artificial island dubbed “Lantau Tomorrow Vision” as part of the government’s efforts to tackle Hong Kong’s housing shortage.

The plan has triggered a backlash from environmentalists and Lantau residents who oppose the idea out of concerns for ocean animals.

“If east Lantau is developed then the problem will be worse, and maybe we won’t have any way to turn back,” Chan says.

Bungy, named after her enjoyment of jumping, died at the age of 18. Chan called the death “like the loss of a child”. He credits the dog with helping steer the course of his life and career.

“You will always guide me to see the rainbow through tearful eyes,” he says.