Is Hong Kong’s government targeting the powerless in elderly welfare scheme change that has scandalised city?

- Critics call out authorities over assumption that less welfare payments will lead to more incentive for older people to continue working

- Former Legco president says Carrie Lam’s controversial stance is to defend report by population committee that she previously led

Wing, 58, has spent most of his adult life as a single father working more than 12 hours a day in hotpot restaurants to raise his daughter.

Typically, he began work at 3.30pm and only finished at 4am. The job meant putting up with cigarette fumes from customers and steam from the pots, for a basic pay of HK$8,000 to HK$9,000 a month plus tips.

Almost 30 years of hard work finally took a toll on his health when, in 2015, he was diagnosed with nasopharyngeal cancer, a rare head and neck form of the disease that starts in the upper part of the throat, near the nose.

His life has been on hold ever since. Aggressive chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatments put the cancer in remission but left him weakened and chronically lethargic.

Wing, who preferred not to give his full name, says: “I tried to return to work but had to leave after a few days. I often have to sit down after walking a distance as I do not have strength in my legs.”

With his 22-year-old daughter barely scraping by to support herself with part-time jobs, Wing has to depend on the Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) scheme, the city’s safety net.

The cancer survivor receives HK$4,000 to HK$5,000 a month, including rent allowances for his public housing unit, but that is barely enough even with only two meals a day.

He was counting down to turning 60, when he would be eligible for a higher elderly welfare payment.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor’s administration then decided to press ahead with changes that meant he would have to wait till 65 to start receiving the higher payment.

Lawmakers from both camps protested against the change last year and, at a Legislative Council welfare services panel meeting in November, called for it to be shelved.

But officials announced in early January that the changes would take effect from February 1.

Only about 6,500 able-bodied CSSA recipients between 55 and 59 – a figure recorded last year – would be influenced by the amendment.

Few could have guessed that in a city of 7.5 million, a policy change would cause so much unhappiness, even among those unaffected. Certainly not Lam. The ensuing uproar plunged her administration into its biggest crisis since she took office in 2017.

For those like Wing, the uncertainty feels unbearable.

Critics accused authorities of playing a numbers game and oversimplifying matters, instead of looking at the human lives affected by the change.

Chasing numbers

The changes that took effect on February 1 centre on those aged 60 to 64 and considered able-bodied.

Previously, everyone over 60 who qualified for CSSA payments received the same standard rate, including those who were disabled or in ill health.

Now there are two groups of able-bodied elderly – those aged 60 to 64 who will get the same rate as those under 60, and those 65 and older who will continue to receive more. There is no change for the disabled and ill.

Under the new scheme, able-bodied adults aged 60 to 64 each get HK$2,525 a month, compared with HK$3,585 for those 65 or older.

The changes do not affect those aged 60 to 64 and already receiving higher rates.

Legislators have condemned the changes, pointing out that the government stood to save only about HK$100 million a year. Critics argue many CSSA recipients turning 60 have health issues, especially after years of manual labour.

Lam countered that the change was not intended to save money, but rather, to reflect social circumstances and the trend to extend the retirement age.

In an attempt to lighten the mood with a line that only drew more fire, the 61-year-old chief executive quipped: “I am over 60 years old but I still work for over 10 hours every day.”

Social welfare sector lawmaker Shiu Ka-chun notes it is also not easy for CSSA applicants to get the higher payment for disabled recipients.

“I have heard of a lot of cases of wheelchair users or the mentally handicapped who have to go for check-ups every six months to prove that they qualify for the higher payment,” he says.

I have heard of a lot of cases of wheelchair users or the mentally handicapped who have to go for check-ups every six months to prove that they qualify for the higher payment

Disputes with doctors over these assessments are common, he adds, saying it was stressful for CSSA recipients as their payments can be reduced after these check-ups.

This was the case for Wing. After his cancer went into remission, the Hospital Authority informed the Social Welfare Department and his payments were immediately reduced from the higher level for those in ill-health to the lower level for able-bodied adults.

‘One mistake after another’

On January 18, following criticism and calls to halt the change, Lam introduced a new “employment support supplement” for those aged 60 to 64 and affected by this.

They would get HK$1,060 per month, the exact difference between the rates that unmarried able-bodied adults aged 60 to 64, and those over 65 would receive under the new policy.

The supplement was intended to encourage able-bodied people in the 60-64 age group to continue working, with no conditions attached.

However, the concession did not appease the social welfare sector and pan-democrats, who pointed out that the affected group would still lose out on supplements and grants amounting to around HK$1,000 a month, which they would have been entitled to before the policy change.

These payments include a long-term supplement of HK$2,240 a year for families with an elderly member for the replacement of household and consumer durables and up to a maximum of HK$500 for spectacles.

University of Hong Kong emeritus professor Nelson Chow Wing-sun accuses the government of labelling people.

“The name ‘employment support supplement’ suggests that you get the supplement because you are working, but if others notice that you are getting it despite not working, they might call you lazy and not deserving of it,” he says.

The name ‘employment support supplement’ suggests that you get the supplement because you are working

He says the government is just making a new mistake to cover its earlier one.

Shiu notes that although there are adjustments to the CSSA payments every year, the base amount, which involves calculating a typical person’s monthly needs including for food, has not been updated for more than 20 years.

He says some items regarded as necessities now may not be included, such as mobile phones and computers which are necessary for children in school.

A week after Lam announced the compromise offer, officials told NGOs running a scheme which helps CSSA recipients find jobs that those aged 60 to 64 who did not join the programme would receive HK$200 less a month in allocations.

That move was condemned by pan-democratic and pro-establishment camps alike, pushing the government to suspend the deduction pending a review, including on special grants and participation in the job programme.

Wing says he is confused by the frequent changes and is worried that the government might eventually take away this HK$200 from him.

Less welfare equals higher employment?

At the heart of the government’s push to change the CSSA policy is its belief that the previous social security arrangement removed the incentive for older people to continue working.

Lam explained that a 2015 report by the Steering Committee on Population Policy, which she led, had found that setting 60 as the retirement age was not in line with other population policies.

But HKU’s Chow notes that with the current statutory minimum wage of HK$34.50 per hour, workers with full-time jobs will get at least HK$7,000 a month, which makes it unlikely that they will apply for CSSA payments.

He says it is not that recipients of CSSA payments do not work, but rather that there are reasons such as poor health preventing them from doing so.

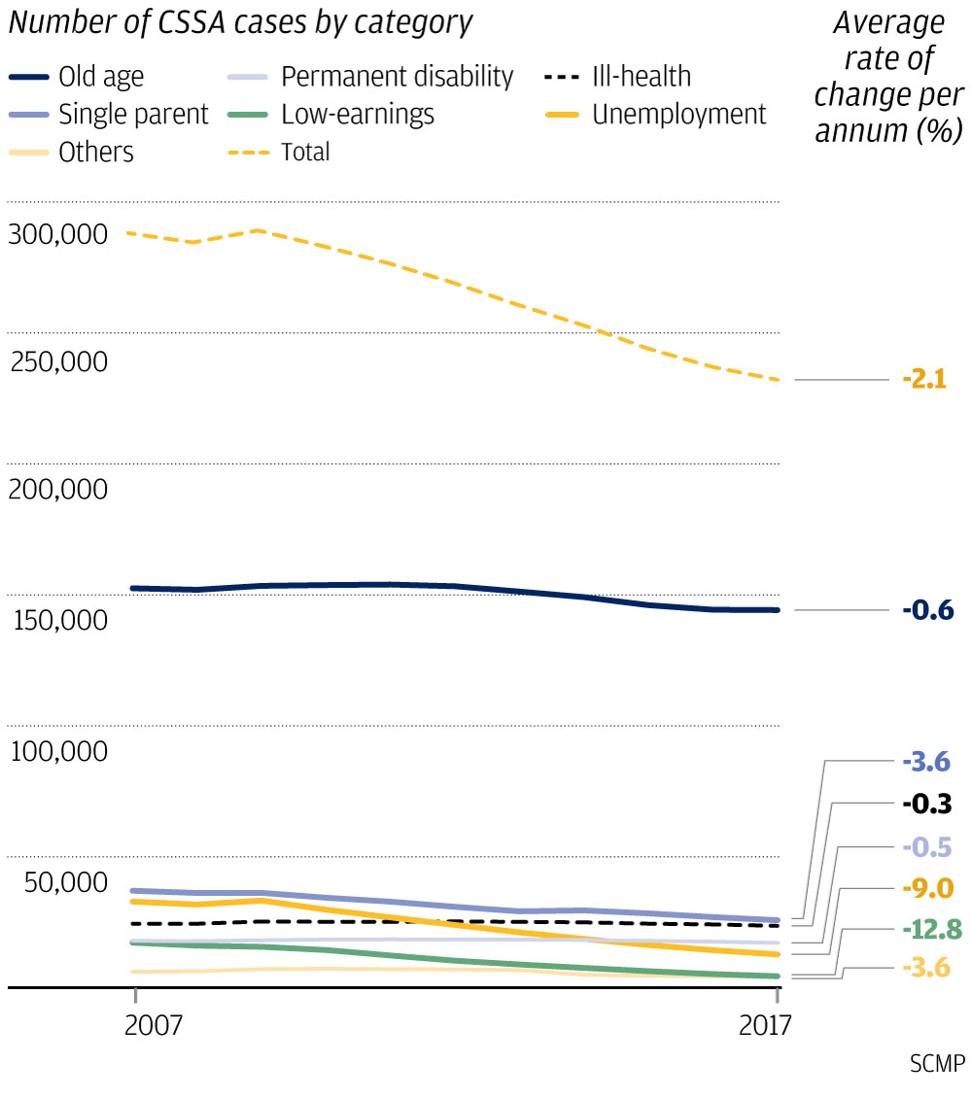

Official statistics show that the total number of CSSA cases has decreased gradually from 288,145 at the end of 2007 to 232,134 as at the end of 2017. Larger drops were noted in low-income earners (-12.8 per cent) and those who were jobless (-9.0 per cent).

Chow, an expert in poverty and ageing matters, says that to encourage older people to continue working, officials should provide them with travel allowance or part-time jobs, which are difficult to find in today’s market.

There is no statutory retirement age in Hong Kong, but Alexa Chow Yee-ping, managing director of AMAC Human Resources Consultants, estimates that 70 to 80 per cent of private companies in Hong Kong have a retirement age of 60.

It was only in recent years that the government raised the mandatory retirement age for many civil servants – excluding the disciplined services – to 65.

Since 2015, around 380 new recruits aged 60 or above have been appointed to the civil service, out of about 173,000 civil servants as of last September.

She says there is no impetus for private companies to follow suit because the earlier retirement age is unlikely to deter potential employees. This is unlike the situation when companies stand to lose out on talent if they do not implement the five-day work week.

Executive Council member and chairman of the Elderly Commission Lam Ching-choi agrees that it makes more sense to have workplaces that are friendly for older workers before pushing ahead with the policy change.

The government has produced no evidence that taking away welfare payments will spur the elderly to keep on working. So why has Lam insisted on pushing ahead with the policy change?

According to former Legco president Jasper Tsang Yok-sing, it is to defend the report by the population committee she led.

Lam, who was once the director for social welfare, has in recent weeks admitted her poor handling of the issue.

But pan-democrats and the social welfare sector have vowed to keep up pressure on the issue.

The pan-democrats intend to scrutinise every item by the Labour and Welfare Bureau and Social Welfare Department in the 2019-20 budget released on Wednesday.

Shiu says he has also written to request a special Legco welfare services panel meeting in June for welfare secretary Law Chi-kwong to give an update. The social welfare sector will meet Law in the summer on the matter.

The Society for Community Organisation, for one, is backing an unemployed homeless man who turns 60 in April in his application for legal aid to challenge the policy through a judicial review.

Nelson Chow says: “The government promotes respect for the elderly but it is not setting a good example.”

Wing says he seldom disagrees with the government’s actions. “But the government is targeting the most powerless this time, so I even took to the streets to protest.”