Born in Hong Kong but living on the mainland: for the city’s cross-border commuter schoolchildren, obstacles to development remain

- The 28,000 pupils who cross the border to attend school in Hong Kong each day have trouble accessing services and often miss out on extracurricular activities

- Social workers and schools speak of frustration in trying to help needy pupils living on the mainland because of a lack of jurisdiction

For around three years, social worker Alex Lui Lap-shan has been trying to get a teenager to return to school in Hong Kong after dropping out when in Primary Six.

But because of the teen’s special situation – as a Hong Kong-born child living in Shenzhen with his mainland Chinese mother and older brother – Lui’s hands are tied.

“When I visited him at home, the child locked himself in his room,” the Hong Kong social worker says.

Lui adds that the single mother is not always contactable and often busy with work as she has to raise two children, the elder of whom is autistic, so she often just leaves the younger son at home alone, giving him money to buy food.

While Hong Kong laws require children to undergo nine years of compulsory education from Primary One to Form Three, Lui admits it is difficult to convince mainland-based parents to get children to return to school in Hong Kong as the legislation does not apply across the border.

Conversely, mainland mandatory education laws cannot be applied to children who are Hong Kong students.

“I can only talk to the parents, but they don’t have to care,” Lui says.

The issue of cross-border pupils has for more than a decade been a thorny one for authorities on both sides of the boundary. While the impact of a ban to restrict mainland women from giving birth in local hospitals implemented six years ago is beginning to take shape, with the number of pupils entering primary school dropping drastically, social workers and education experts say there are still many challenges faced by the 28,000 who cross the border to go to school that need to be tackled urgently.

Falling out of the safety net

Much of the help provided by the government has been dedicated to mitigating the long and tortuous journeys to school undertaken by the pupils and alleviating the excessive demand for school places in districts close to border control points, such as in North district.

But it is difficult to enforce the nine years of compulsory eduction on this particular group of cross-border pupils and keep them inside the system.

In Hong Kong, schools must report to the Education Bureau if a pupil is absent for seven consecutive school days without a reason.

But school-based social workers cannot go to the mainland for home visits due to a lack of protection or insurance cover for them, Lui says. Cases are thus referred to his NGO, which is the only one in Hong Kong that receives a subvention from the Social Welfare Department to provide a cross-boundary social service.

While the NGO can contact the families, that does not solve the problem, he says, as shown by his fruitless attempt to get the child who dropped out in Primary Six back to school.

Lui, who works at the International Social Service Hong Kong Branch (ISS-HK), says pupils can often get rebellious around Primary Five and Six and play truant. In these cases, he admits he can only continue to see the pupil and encourage the parents to go for parenting classes at the NGO.

Celeste Yuen Yuet-mui, an associate professor at Chinese University’s department of educational administration and policy, who does extensive work on cross-boundary pupils, recalls a tragic murder-suicide case involving a cross-border child, in which the school was limited in what it could do to help.

“The kindergarten’s principal once told me that they found out one of the parents of a pupil had jumped off a building with the child,” she says.

While the whole school was very upset and shocked by the ordeal, the principal had said the kindergarten felt helpless as it happened on the mainland so they could not just go there despite wanting to help the deceased child’s relatives.

Yuen estimates at least 20 per cent of cross-border pupils come from needy homes.

Because of the sensitivity of the situation, the Post was unable to contact such families.

A bureau spokeswoman says the Education Ordinance authorises the permanent secretary of education to issue attendance orders to parents who fail to ensure children aged between six and 15 attend school regularly in Hong Kong unless they have a reasonable excuse.

A Social Welfare Department spokeswoman says that in case of needs, school social workers would refer the cross-boundary students and their families to ISS-HK for services outside Hong Kong and work with the related social worker to support the students in need.

Education and developmental issues

With the children having to spend long hours travelling to school and their parents being less familiar with Hong Kong education, their academic studies would naturally be expected to be hampered.

But Yuen says the pupils do not suffer such a disadvantage, with some even performing better than children living in the city.

“According to their teachers, they might be more resilient, having to cope with the long journeys and not having their parents around,” she says.

Yuen notes the high expectations of their parents also push them to concentrate and be more dedicated to learning.

But she says it is a different story in terms of whole-person development.

Because of their long travelling hours, they are more limited in taking part in extracurricular activities, socialising with peers outside the school setting and experiencing other parts of society such as visiting museums.

Yuen says whole-person development is an important social acquisition if a student is to get a good job or into a top university.

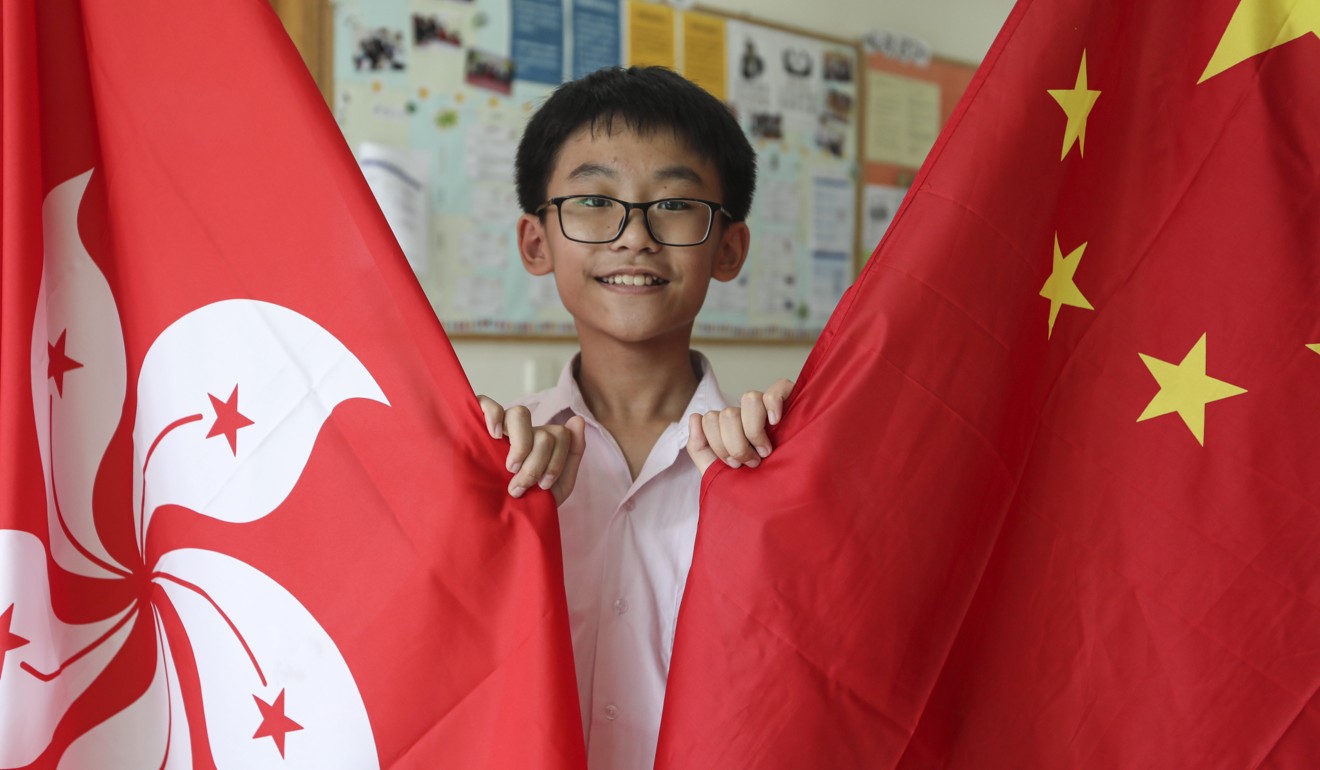

Secondary One cross-border pupil Qiu Tim’s parents do not have too much to worry about over his studies, as he is enrolled in one of the top schools in North district, which uses English as a medium of instruction.

However, after entering secondary school, Qiu had some difficulty with a new subject – liberal studies.

One of the core subjects for the city’s main college entrance examination, liberal studies aims to help students develop multiple perspectives on issues such as those relating to Hong Kong, modern China, globalisation and public health.

“It would be good if we could have tuition classes near our home for this subject as we do not learn it in mainland China,” says Qiu’s father, who did not wish to be named.

While Qiu could depend on ISS-HK for tuition classes back in his primary school days, limited resources mean the NGO does not offer such lessons for secondary school students.

As such, Qiu can only get help with the subject when he is in school.

His parents also do not like the idea of him going for tuition in Hong Kong as that would mean he gets home very late.

Where is home?

Those who work with or observe these cross-border pupils say another challenge many face is a lack of sense of belonging and familiarity with Hong Kong.

From his frontline experience, Lui says their knowledge of the city is often limited to regions near their schools, such as North district or Yuen Long and Tuen Mun.

“Hong Kong for them is these places and they are not familiar with the culture of Hong Kong and its people,” he says.

For example, things that might be common knowledge to Hongkongers, like the outlying islands of Cheung Chau and Lamma, and Government House, are foreign to many cross-border pupils and their parents, Lui says.

“It is like you are not a real citizen in society and only consume the education, it is not healthy,” Yuen remarks.

She adds that these pupils feel like outsiders in both Hong Kong and the mainland.

But both Yuen and Lui agree there is a desire to be in Hong Kong.

Yuen notes that these pupils enjoy a sense of connection with the city.

In their work with cross-border pupils, Lui and his colleague Florence Wong Yim-ping, director of development for services on the mainland at ISS-HK, note that when asked, the children always say they are Hongkongers.

Where do we go from here?

With many of the cross-border pupils born to parents who are both mainlanders and who do not have to pay Hong Kong taxes, there has been growing discontent against the children for using local public education resources.

Moreover, many families in Hong Kong’s northernmost district have had their lives turned upside down because of an unprecedented influx of pupils born to parents from the mainland crossing the border to study and competing for school places.

But with six years having passed since the Hong Kong government imposed a ban on non-local pregnant women whose husbands are not Hongkongers from reserving hospital beds for delivery, the numbers crossing the border are expected to fall in the coming school year.

While there are no statistics for children born to two mainland parents, official figures showed that from 2013 there were on average fewer than 1,000 children per year born in Hong Kong to mainland women whose spouses were not Hongkongers, compared with a peak of 35,736 in 2011.

Coupled with the fact that from 2017, these children could apply to Shenzhen public primary schools even if they do not have a mainland household registration, the crisis seems to have subsided.

While critics say mainland parents need to be more responsible for their decision to have children in Hong Kong, advocates for the welfare of the pupils believe more could be done to help them.

“We still have not come up with a consistent policy and way to help them develop,” Yuen says, lamenting that most government help has been merely of a logistical nature, such as transport subsidies and pushing the school starting time back to reduce congestion at checkpoints.

She calls for more flexibility in government subsidised extracurricular activities, such as holding them on the mainland over the weekend.

Some people might reject these children but the reality is that they were born in Hong Kong and are legally Hongkongers

Lui echoes the idea, adding there could be less rigidity in how government subsidies for students can be used, such as in buying services for liberal studies education in Shenzhen.

For example, he recalls that talks he gives on the mainland to introduce Hong Kong’s outlying islands have helped pique the interest of cross-border pupils and their parents. He also takes families to Hong Kong for excursions to get to know the city better, such as to Stanley and the Hong Kong Zoological and Botanical Gardens. But many activities charge a fee.

The latest figures show there are currently 27,909 cross-border pupils, but Lui says the NGO can only cater to less than 3 per cent.

Wong hopes for more resources so that they can extend tuition services to secondary school pupils.

“Some people might reject these children but the reality is that they were born in Hong Kong and are legally Hongkongers,” Lui says.

He adds that these children may contribute to Hong Kong and be part of the city’s shrinking workforce when they grow up, if they can get a sense of belonging to the city.