Macron admits systematic torture by France in Algeria war, as he grapples with a brutal colonial legacy

President issues statement in call for truth about the 1957 disappearance of anti-colonial activist Maurice Audin, who was tortured by the French army

France formally acknowledged its military’s systemic use of torture in the Algerian War in the 1950s and 1960s, a step forward in grappling with its colonial legacy.

President Emmanuel Macron issued the statement in the context of a call for clarity about the fate of Maurice Audin, a 25-year-old mathematician and anti-colonial activist who was tortured by the French army and disappeared in 1957, during Algeria’s bloody struggle for independence from France.

Audin’s death is a specific case, but it represents a cruel system put in place at the state level, the Elysee Palace said. “His disappearance was made possible by a system that … allowed law enforcement to arrest, detain and question any ‘suspect’ for the purpose of a more effective fight against the opponent,” read Macron’s statement.

“It permits us to advance,” he said. “To exit from denial and to advance in the service of truth.” Stora accompanied Macron Thursday afternoon on an official visit to Audin’s widow, Josette Audin, 87.

Macron, 40, is the first French president born after the war and has shown a rare willingness to wade into the memory of Algeria, arguably the most sensitive chapter in the French experience of the 20th century and one that has had a profound influence on the country’s current political institutions.

Conquered by France in 1837, Algeria was a colony but also cast as an integral part of the country. By the 1950s, it was home to millions of French settlers, and when France was forced to give up overseas possessions in West Africa and Southeast Asia, it always held on tightly to Algeria.

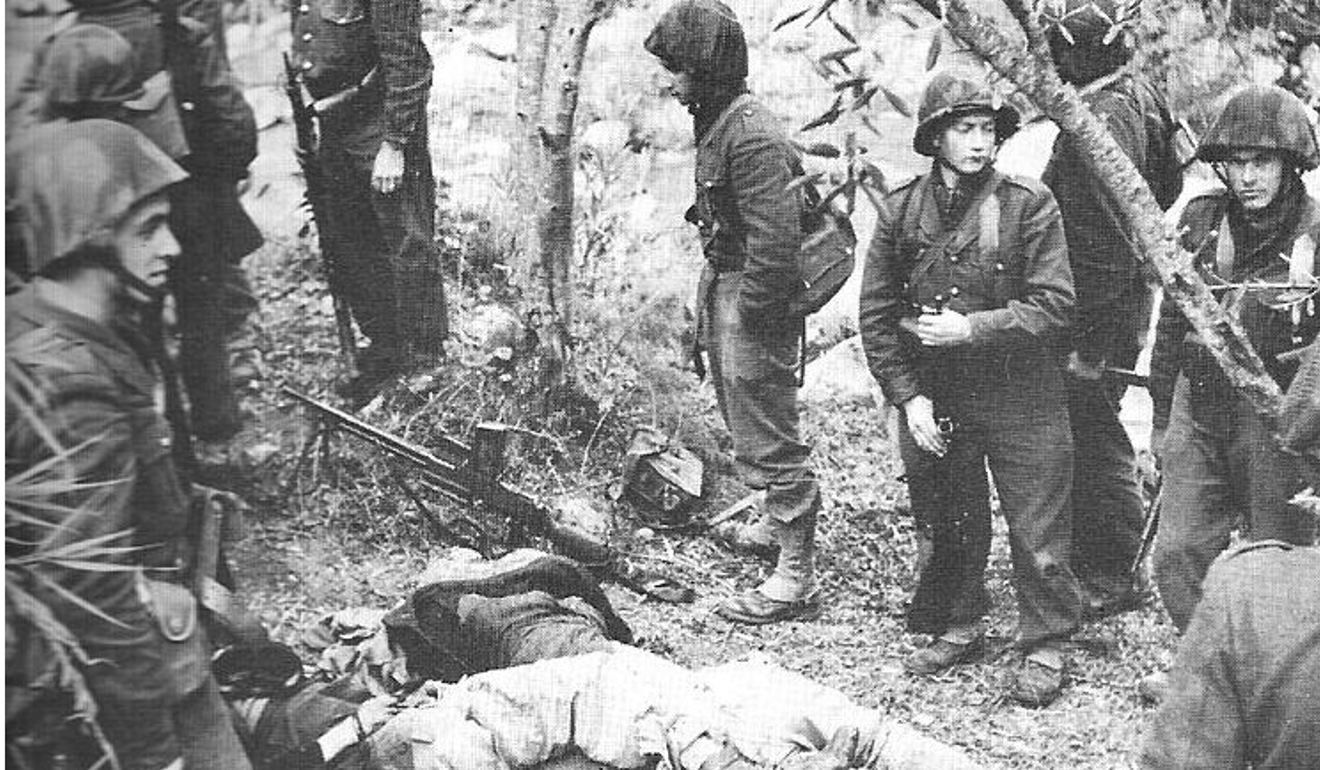

When the country revolted in 1954, the suppression was savage. “Everyone knows that in Algiers the men and women arrested in these circumstances did not always return. Some were released, others were interned, others were brought to justice, but many families lost track of one of their own that year, in the future capital of Algeria,” the Élysée statement read.

On a visit to Algeria in February 2017, Macron, then a presidential candidate, called French colonialism “a crime against humanity,” a remark that reignited a bitter national debate.

In addition to recognising state-authorised torture, Macron called for the opening of archives concerning those who disappeared, such as Audin.

“A general dispensation, by ministerial decree, will be granted so that everyone – historians, families, associations – can consult the archives for all those who disappeared in Algeria,” the Élysée statement read. “We’re putting the issue of the missing in the centre.”

Macron’s statement drew hopeful comparisons to the last time a French president publicly atoned for the sins of the past – Jacques Chirac’s 1995 apology for France’s collaboration in the Holocaust, specifically in facilitating roundups of its own citizens who were then handed over to the Nazis.

Chirac’s speech represented a major shift in the way the French public and political establishment understood its past. In the years that followed, a more nuanced picture of France’s role in the Holocaust was taught in national schools, and memorials were erected around the country, including a prominent Holocaust memorial museum in central Paris.

Some wonder whether similar action on Algeria, once unthinkable, could now be possible.

The two events are vastly different, said Stora, who was born in Algeria in 1950 to a Jewish family that then left for France in 1962, in the midst of the upheaval. But he said Macron’s admission nevertheless presented many former colonial subjects, including French Muslims of Algerian origin, “the sentiment of being respected in their history.”

“It will be very difficult for political successors to walk this back,” Stora said.

For Yasser Louati, a Muslim community organiser and prominent activist against Islamophobia in France, Macron’s statement is a “historic moment” but one that does not go far enough.

Although the French president has drawn attention to colonial crimes that occurred in Algeria, there is still a reluctance to confront the violence that occurred in France itself, such as the brutal massacre by French police of pro-independence Algerian protesters in Paris in October 1961. Historians estimate that as many as 200 were killed in that event.

“We also have to deal with the legacy of the colonial era,” Louati said.

France’s current system of government came into being in 1958, in response to an attempted coup by French generals in Algiers.

“Giving powers to the president of the republic, strengthening the executive to the detriment of the legislative branch – all that is Algeria,” Stora said. “French political culture lives in the memory of that war.”