Why President Temer’s military takeover of Rio de Janeiro harks back to Brazil’s years of dictatorship

Thousands of troops have been deployed to the city since last July, not to overturn a president, but to take charge of the security situation after months of escalating crime

The ghosts of Brazil’s dictatorship are stirring in the wake of President Michel Temer’s order for the army to take over policing in Rio de Janeiro.

There’s no direct comparison between the Rio operation and the 1964 coup that brought two decades of military rule to Latin America’s biggest country. In this case, the military is not overturning a president – it’s just taking charge of Rio state’s security situation after months of escalating crime.

But the echoes have been loud enough to force the government into extraordinary denials.

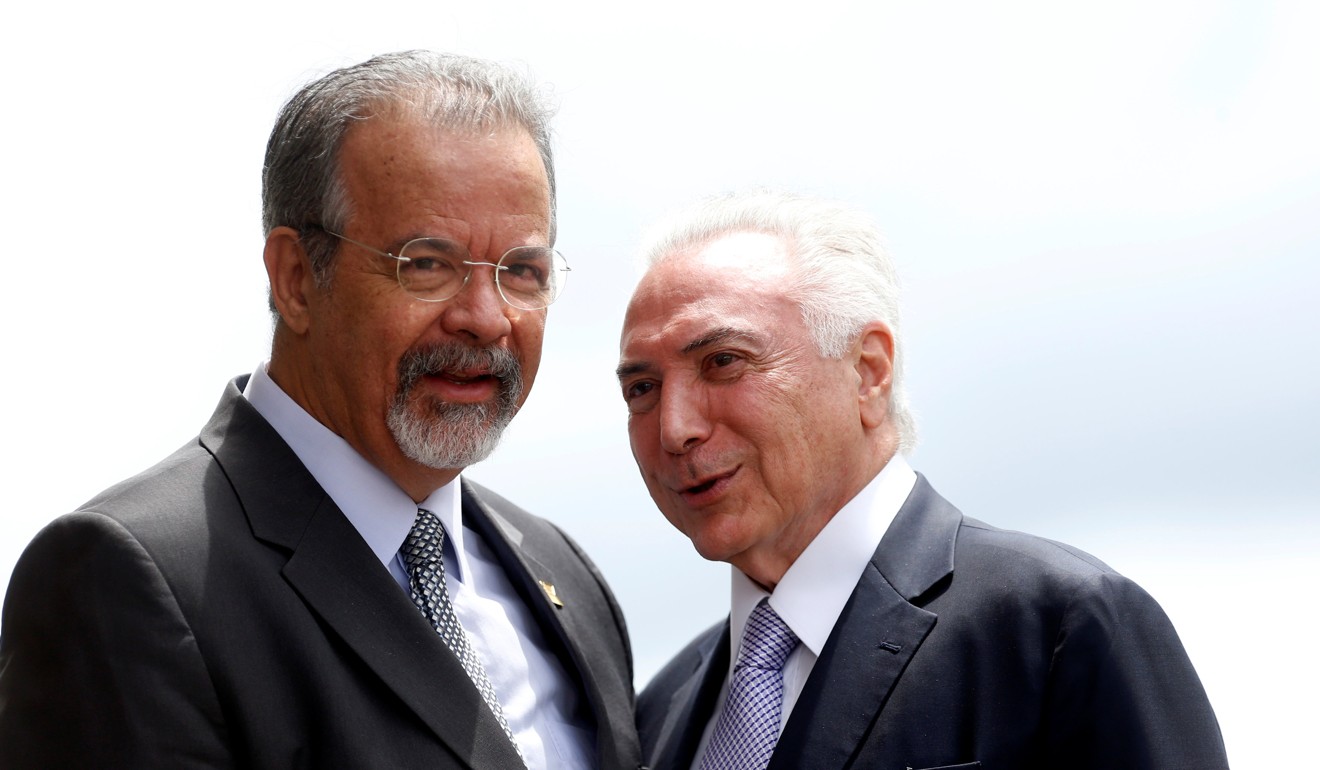

“I’m going to tell you how many marks I give the idea of a military coup: zero,” Temer told Radio Bandeirantes on Friday.

The centre-right president went on to say that there was “no mood” in the military or population for a coup.

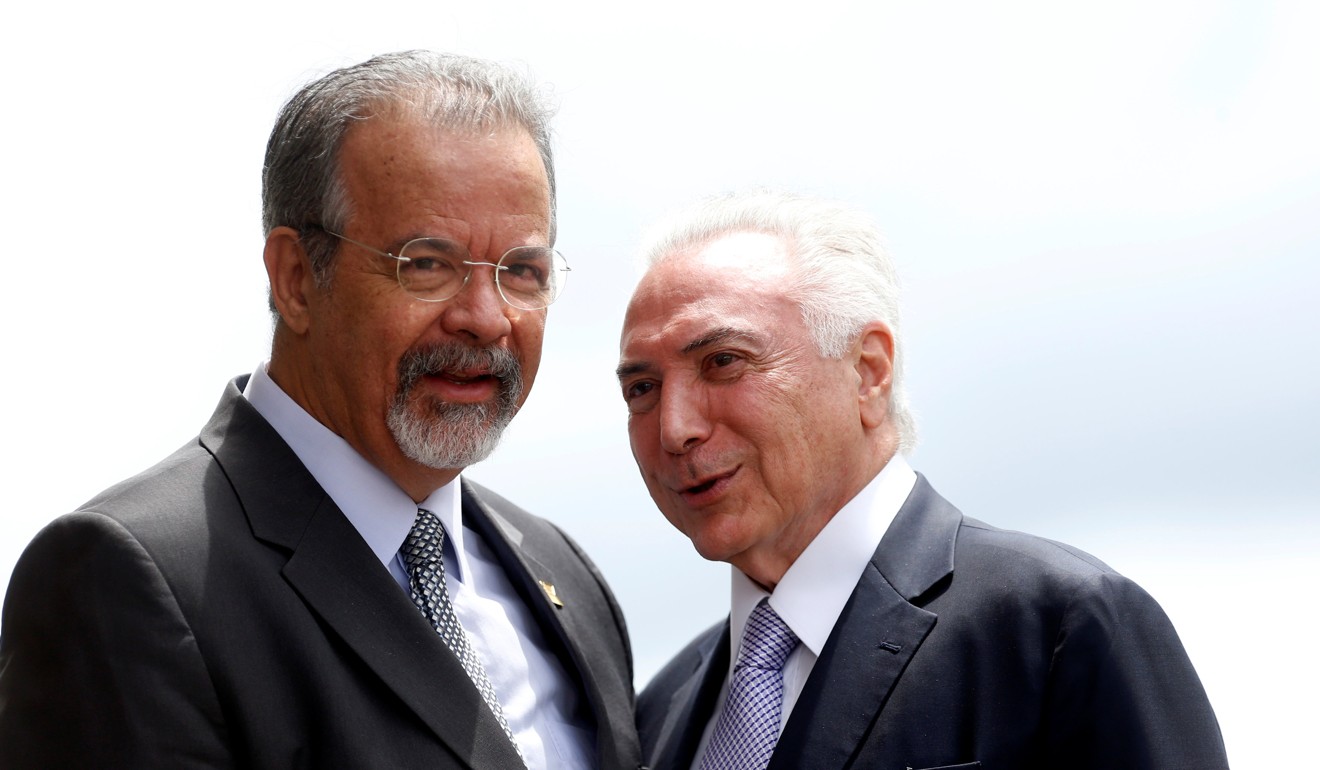

Earlier, the defence minister, Raul Jungmann, stated “there is no risk to democracy … On the contrary, we are strengthening democracy”.

Over the last decade, Rio residents have grown used to seeing camouflaged soldiers support the police in their battle against powerfully armed drug gangs.

Some 8,500 troops arrived last July in an ongoing deployment to help with operations in favelas, the latest of which took place on Friday in western Rio. During the 2016 Olympics, troops focused on securing tourist areas, patrolling with rifles among the bathing-suit clad crowds of Copacabana and Ipanema.

But the intervencao, as it is called in Portuguese, is different this time.

Now the army is not only helping out – it is taking full charge, with generals replacing the entire civilian leadership of the police.

This has not happened anywhere in Brazil since democracy returned in 1985.

Facing an understandably nervous public, the government made what looked like an immediate public relations blunder by suggesting that mass arrests and mass searches might become the norm.

That would mean, for example, that an entire street, rather than a single house, could be subjected to an intense raid.

There was strong backlash, including from Brazil’s highest-profile anti-corruption prosecutor, Deltan Dallagnol.

The government has softened its message on the collective searches.

But there are still widespread fears that military intervention will become a blunt instrument endangering poor and defenceless people in the favelas, while doing little to eradicate narco gangs.

A short video made by three young black men about surviving encounters with police – including advising against carrying a long umbrella that could be mistaken for a gun – went immediately viral on social media.

“The intervention in Rio is an inadequate and extreme measure that causes concern because it puts the population’s human rights at risk,” said Amnesty International’s director in Brazil, Jurema Werneck.

Temer made it clear on Friday that the army will use deadly force when justified. But rights activists, weary after years of botched police operations and stray bullets, ask who will hold the soldiers to account.

The army wants troops to be subject only to military courts, while the police it is working alongside have to face regular courts.

Adding a politically explosive twist to that already complex issue, the army’s top commander General Eduardo Villas Boas said this week he wants “a guarantee of being able to act without risking a new truth commission”.

He was referring to the National Truth Commission, a body set up by former leftist president Dilma Rousseff to examine appalling human rights abuses committed during the military dictatorship.

Many saw the commission as a way to air painful memories and promote reconciliation, even if an amnesty meant that confessed torturers revealed in the commission’s final 2014 report could not be tried.

Villas Boas, however, revealed the army’s nervousness and perhaps lingering resentment.

Another key figure in the Rio intervention – Temer’s security minister Sergio Etchegoyen – has previously lambasted the truth commission’s report as “pathetic”.

Etchegoyen’s father, Leo, served in high positions during the dictatorship, while an uncle allegedly headed the so-called “House of Death” – a property near Rio where mainly far left political prisoners were fatally tortured.

One story fuelling conspiracy theories has been that Rio is only a trial balloon for more widespread military takeovers. Last year, Etchegoyen himself described Rio de Janeiro as a “laboratory”.

This week, though, he backtracked partly on this, stressing there was “currently” no need for a takeover in other states.

But on Friday, Temer stirred the pot when he revealed that he had considered extending the federal government’s takeover from the Rio security services to the entire state government.

“It was a conversation we had but it was soon discarded,” he told Radio Bandeirantes.

“It was a very radical thing and I quickly refuted it,” he said.