A dead drug lord’s mansion and China’s new Colombian connections

Beijing is trying to break further into Latin America’s lucrative market, but history and cultural differences have been stifling trade ties

Set in one of the quietest, safest and most exclusive neighbourhoods in Bogota, the site for China’s new embassy is a huge statement of intent for its operations in Colombia and Latin America.

At more than 5,000 square metres, the land reportedly cost US$18 million – a small amount in the global economy but a princely sum in the local market.

On a sunny weekday afternoon, well-dressed Colombians stroll past its iconic 3.5 metre-high stone walls on their way to work.

Topped with coils of barbed wire, the imposing exterior appears purpose built for the high security and privacy needs of a superpower’s future diplomatic headquarters.

But the site, which is now under siege from ivy and local graffiti artists, is better recognised for its entanglement with Colombia’s dark and violent history.

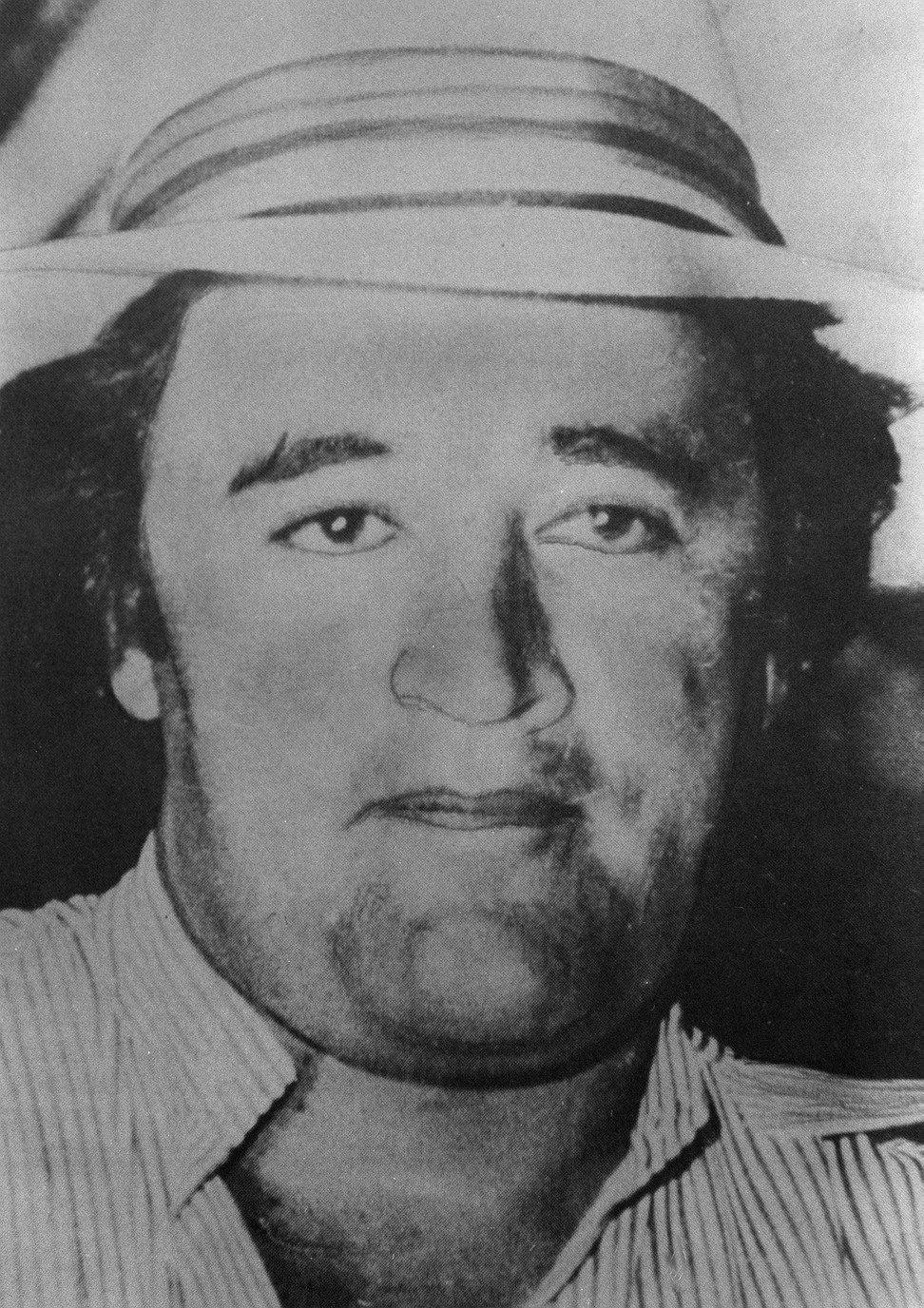

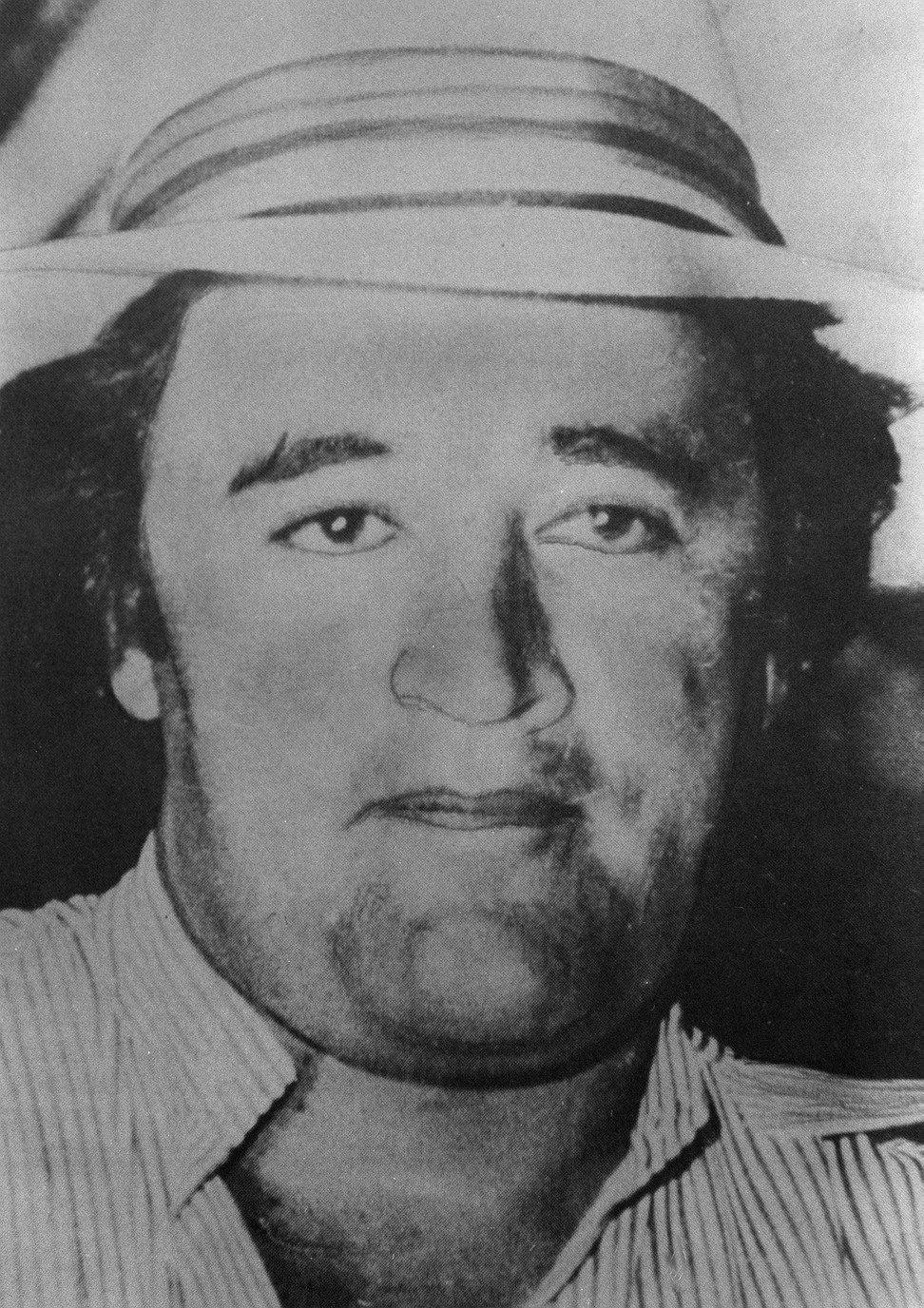

Before being left to rot, it was one of the homes of Jose Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha, a high-ranking member of Pablo Escobar’s Medellin cartel.

“Casa Gacha” was bought when the Medellin cartel supplied about 90 per cent of the world’s cocaine. Members splashed out on properties in the most affluent areas of the country in an ostentatious display of wealth in defiance of the nation’s elite, who rejected them.

After unleashing indiscriminate terror across the nation, corrupting politics and almost turning Colombia into a “failed state”, the narcos’ image locally was far from glamorous.

Some believe the building’s foundations include a system of secret tunnels where the cartel hid the bodies of countless victims they murdered.

It appears that China – although a relatively superstitious nation – may have overlooked the significance of acquiring a building which once belonged to one of the nation’s biggest drug lords.

But according to Benjamin Creutzfeldt, resident postdoctoral fellow for China-Latin America-US Affairs at Johns Hopkins University, it is better viewed as sheer pragmatism.

“It is tempting to interpret the Chinese acquisition of Casa Gacha as having some sinister symbolism,” said the academic, but it is “more helpful to see it as evidence that Colombians are finally burying some of their violent and blood-soaked past and moving on and to understand the Chinese really are pragmatic people … It can only improve the image and standing of China in a society that has historically rejected contact with East Asian people and continues to view them with suspicion.”

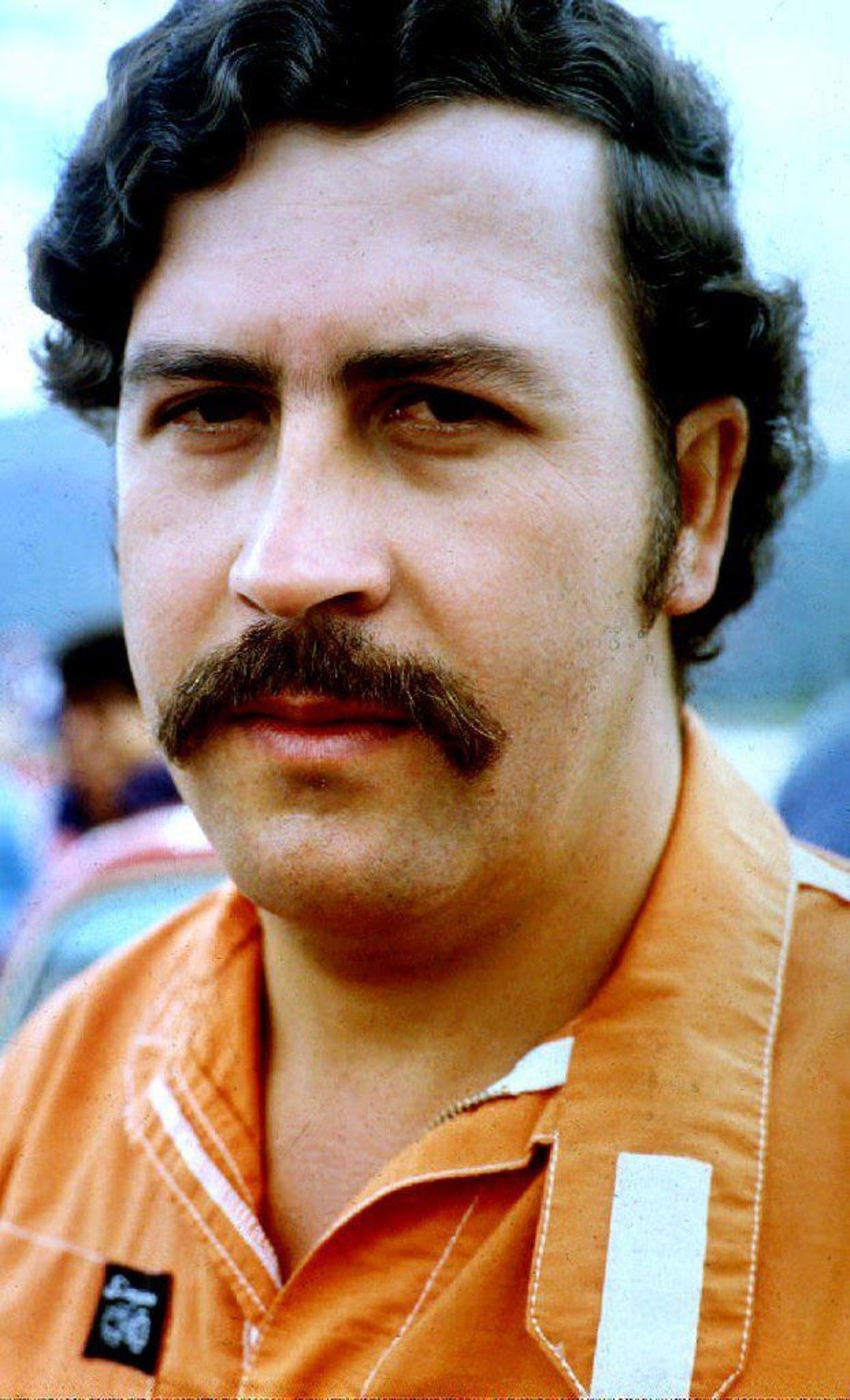

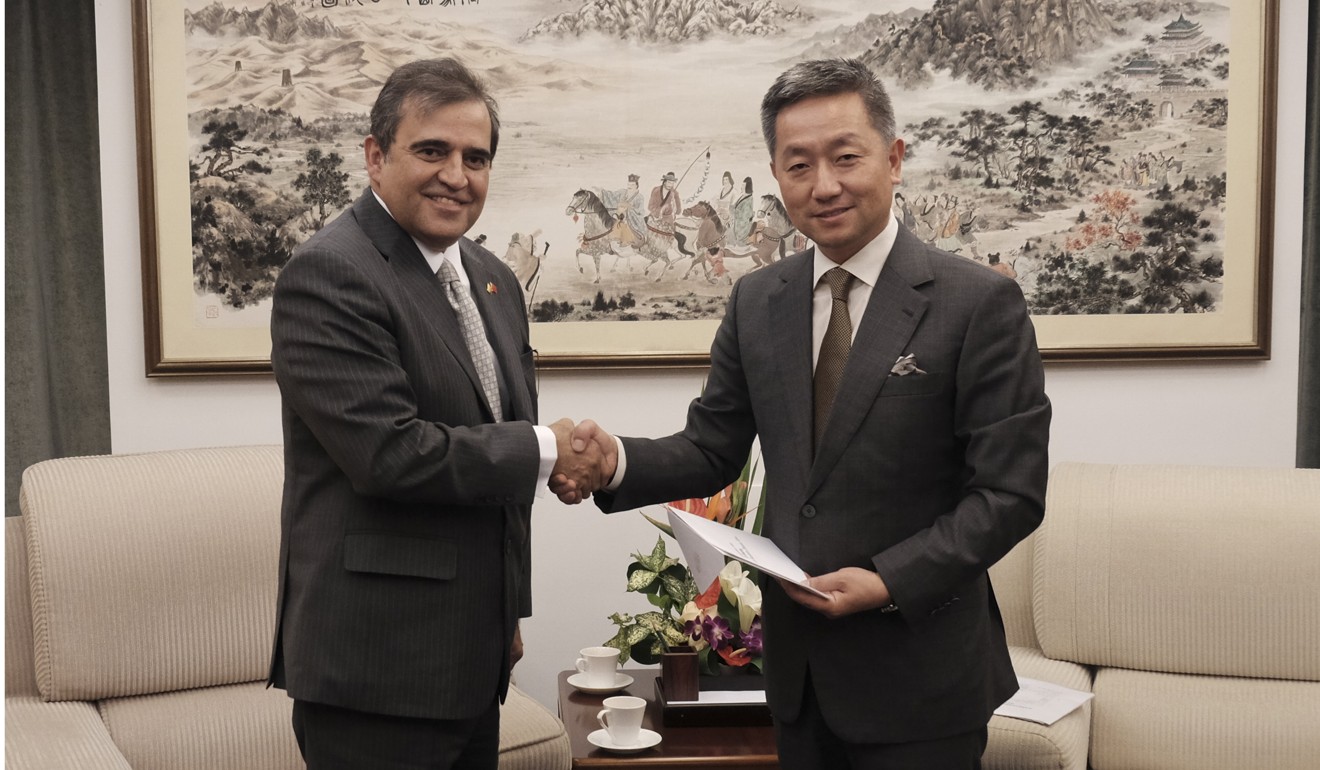

China’s economic activity in the Andean nation has rapidly increased in recent years. According to Colombia’s ambassador to China Oscar Rueda Garcia, the number of Chinese businesses grew from 20 in 2015 to “nearly 70” in 2017 as post-peace agreement Colombia seeks foreign investment in areas such as infrastructure, energy and manufacturing.

China mainly sells machinery and electrical, hi-tech and textile products to Colombia while Colombia exports crude, scrap metal and raw furs to China.

Beijing’s customs data shows China exported US$7.4 billion worth of products to Colombia in 2017, a rise of 10.1 per cent from 2016, while Chinese imports from Colombia surged 35.8 per cent to US$3.9 billion last year.

But not everyone is welcoming the arrival of foreign capital with open arms.

In the Cordoba region along Colombia’s Caribbean coast, energy firm China United Engineering Corporation’s power station has generated strong opposition and controversy.

After several delays and legal cases, relations soured to a point in 2012 when Colombian workers reportedly threatened the Chinese management team who in turn barricaded themselves in their offices in a form of kidnapping.

Emerald Energy, a Chinese petroleum company extracting oil at the foot of the Colombian Amazon, has also faced setbacks.

Local opposition to extractives projects which could damage Colombia’s diverse ecosystems has grown in recent years due to social and political shifts, but Emerald Energy was met with particularly strong opposition, as doubts were expressed over the legitimacy of the company’s environmental studies.

These cases aside, issues are not surprising due to a “reciprocal disrespect” and xenophobia resulting from minimal historical links between the countries, Creutzfeldt said.

Even seemingly minor cultural differences such as Chinese food and different working hours can cause friction, he said.

With Colombia opening up to the world and a new wave of Chinese immigrants being posted there by their companies or arriving on their own, this has begun to change.

But numbering only 28,000, the Chinese community in Colombia is still far lower than places like Panama, where the 300,000 Chinese living there make up almost 8 per cent of the population.

Qin Zhou from Changsha in China’s Hunan Province, lived in Colombia for a year-and-a-half teaching Chinese. She said the locals gave her “such a warm welcome”.

“Most of them are so friendly and warm-hearted”, Zhou said, but admitted there was some stereotyping.

“Children think the Chinese eat every animal like dogs, snakes and mice” while older Colombians think Chinese people “still live in the age of Chairman Mao”, she said.

Zhou added that others thought the Chinese are “indifferent”, “mysterious”, or “impolite”.

Although they may appear trivial, such stereotypes are often accompanied by deeply-entrenched negative views.

The average Colombian thinks the Chinese are “a plague”, said Juan David, a Colombian lawyer who studied in China and now promotes trade between the countries.

“But it’s not true … my experience in China was stunning.”

Recently, local Chinese communities have begun to sense a growing anti-Chinese sentiment as their presence grows.

On April 27, 500 business owners at a Bogota shopping centre marched to the local council against the “invasion of Chinese products” which one participant said was resulting in local businesses “dying”. In May 2016 a similar march drew 5,000 people.

In November last year the Chinese community held its own march to China’s embassy. They demanded an end to what they called the closing of “legitimate” Chinese businesses by authorities, claiming the political system reflects local anti-Chinese sentiment.

A former senior figure at the National Ministry of Mines and Energy said some Chinese businesses are failing because of their lack of cultural sensitivity.

“In Africa where Chinese companies operate there is no requirement or expectation of social responsibility for international companies … they have a really bad reputation there,” the source said. “But in Colombia there are and the communities request it.”

The source said some Chinese businesses do not take into account social responsibility expected from them or build sufficient relations with local communities, so they are often seen as stripping regions of natural resources without generating development.

“Chinese companies have to learn to that their arrival has to be better organised, planned, and more concentrated in social communications and relations”, they added.

China has made more efforts in recent years to establish itself in Colombia with the country’s former president Juan Manuel Santos visiting Beijing in 2012 to strengthen relations and trade.

“For the Chinese, the Colombian market is very important in South America … it’s a strategic entry point for them as it is one of the most important economies in Latin America with a high population compared with other countries and a huge potential to develop projects” said Jaime Suarez, executive director of the Colombia-China Chamber of Investment and Commerce. “And for Colombia, China is an attractive market – principally for imports”.

Due to “strong advantages in price and quality”, China has become Colombia’s second-biggest partner for imports after the United States.

But despite a Colombia-China free-trade agreement being proposed some six years ago to boost trade, it appears little progress has been made.

In fact, moves such as the prohibition of cheap Chinese imports of the nation’s iconic vueltiao hat suggest that improving trade with China may not be a popular move.

But if politics offers little hope of improving relations, perhaps it could be the Chinese communities and businesses themselves who can break down the cultural barriers and pave the way for progress.

“We have identified that Chinese businesses and businessmen are trying to adapt to Colombian culture through various means … our culture, products, parties and Colombian idiosyncrasies,” said Suarez. “Most of the time in the beginning Chinese businessmen only relate themselves with other Chinese businessmen, but later on they begin to get involved with the cultural activities of Colombia.”