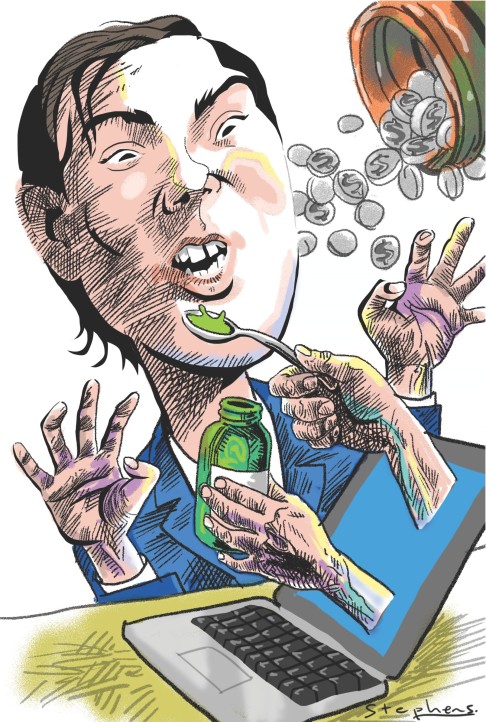

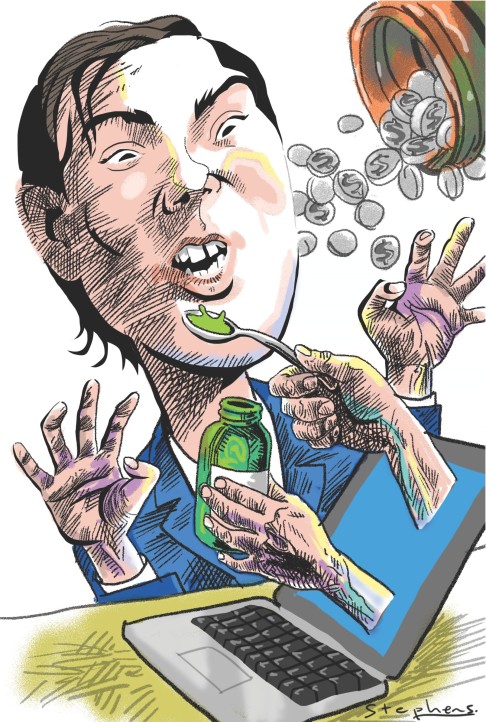

Online shaming forces 'most hated man on internet' to back off from drug price rise (sort of)

Martin Shkreli's firm tried to increase the cost of a drug used to treat Aids.

Online shaming is frequently in the news these days, typically for the very worst reasons: ruined lives, lost jobs, frothing mobs in a frenzy to steamroll the subject of their dissatisfaction. But here at last is one case where the mob may have done some good.

In an interview with the American Broadcasting Co last Tuesday night, chastened Wall Street bro Martin Shkreli - previously, internet public enemy No1 - announced that he actually wouldn't jack up the price of an important Aids drug.

The New York Times reported the mark-up last Sunday in a blood-boiling piece on Shkreli's pharmaceutical start-up; his company bought Daraprim, a generic medication used to treat infections in Aids patients - and then raised the price from US$13.50 a pill to more than US$700.

Predictably, and justifiably, the story sparked a thunderclap of outrage on Twitter, where Shkreli maintained an absurdly flippant personal account. In the three days after the Times story went online, more than 50,000 people tweeted at Shkreli's handle - many of them calling him things like "the worst person in America" and "the personification of evil".

Shkreli was memed and eviscerated on Reddit; at least one Twitter user published Shkreli's personal contact information, a practice known as doxing. On Pastebin, another vigilante published the emails of all his employees. In other words, the online mob did all the worst, most destructive things that we tell people never to do - and it worked, spectacularly, for the greater good. Shkreli's backflip means people will retain their access to a potentially life-saving medication.

Shkreli's actions were shocking for a simple reason: It was a rare moment of complete transparency in health care, where motives, prices and how the system works are rarely talked about so nakedly.

"I think it reflects a widespread appreciation that pricing for drugs is entirely irrational in [the United States], and the pharmaceutical industry has total control over prices and there's no rationality to the system," said Peter Bach, a physician and director of health policy and outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre in New York.

"It's such a perfect, crystalline example of everything that can be done, given the lack of rationality in the system, and the total bankruptcy of the justifications for high drug prices."

Arthur Caplan, director of the division of medical ethics at New York University Langone Medical Centre, said it was relatively rare even to know how much a drug costs to manufacture or what a fair retail price would be.

Drug companies often set prices and try to deter questions about costs by "ringing the innovation bell" - suggesting that to limit profits in any way will leave life-saving cures to languish in test tubes, Caplan said.

"No one is explaining the price. No one even knows what the price is. And no one knows what a fair price is," he said. "Shkreli was transparent - and the industry, the whole health-care industry, is not transparent. It's not even close. It's the most obtuse, dense, incomprehensible pricing structure."

To hear Shkreli tell it, his Turing Pharmaceuticals is the little pharma that could: a start-up that bought the only treatment for a severe but rare parasitic infection and then raised the drug price more than 4,000 per cent so the company could begin to turn a profit.

"It's a great business decision that also benefits all of our stakeholders," Shkreli wrote.

He also compared Turing favourably to other companies that charge more for medicines used to treat less severe and more common diseases.

"To me, I think the pricing discussion is inappropriate, because there are far larger targets to focus on than little Turing Pharmaceuticals," he said.

Shkreli plays the villain well - the former hedge-fund manager turned pharmaceutical speculator posts smug photos of himself on his Twitter feed, lords his youthful confidence with aplomb, and isn't afraid to say what he thinks - even, and perhaps especially, if he realises it might annoy some people.

Before he incited the ire of the internet last week, he had already gained notoriety as a hedge-fund manager who wouldn't hesitate to contact the US Food and Drug Administration personally to weigh in on whether the agency should grant approval for a drug that he also happened to be short-selling - a term for betting that a stock would go down.

"I am a fund manager who will benefit substantially if the FDA adopts my viewpoint," Shkreli wrote to the FDA in 2010, exhorting it to turn down the drug Afrezza while he was short-selling its maker, MannKind. "Despite these conflicts, the FDA should review my statements with care and knowledge of my integrity."

He is also used to being under fire. A watchdog group, Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, in 2012 requested a federal investigation into his short-selling activities. He is being sued for US$65 million by Retrophin, a company that he founded and got pushed out of "because of serious concerns about his conduct", according to a statement from the company.

Retrophin said it received a subpoena from the US attorney for the Eastern District of New York requesting information about its relationship with Shkreli and the hedge fund where he worked.

But Shkreli's decision to raise the price of a drug that treats a rare but severe infection that afflicts HIV and cancer patients and was approved decades before he was born incited a level of wrath that made him turn his Twitter account to private.

A spokesman for Impax Laboratories, the company that sold Turing the rights to Daraprim for US$55 million, said he could not comment on whether the drug was profitable. "It's been around a long time," Mark Donohue said. "It was not a core product."

Pharmaceutical companies that make new therapies often justify prices by saying they will recoup the investment needed to research, develop and gain approval for new drugs. With Daraprim, all that money had already been spent, so radically raising its price seems to some more the tack of a hedge-fund manager who discovers an undervalued asset than a reflection of drug-industry practices, analysts said.

Even PhRMA, a trade group that frequently finds itself defending the drug industry against critics, pointed out that Shkreli's company, Turing, was not a member and slammed the door on him.

"PhRMA members have a long history of drug discovery and innovation that has led to increased longevity and improved lives for millions of patients," PhRMA president John J. Castellani said. "We do not embrace either their recent actions or the conduct of their CEO."

What are we to make of all this? It complicates the already foggy ethics around online shaming and social vigilantes. And maybe it should be complicated, argued Jennifer Jacquet, a professor at New York University.

Jacquet has advanced the theory that public shame comes in different flavours: Much of it is in essence bullying and much of it is disproportionate. But shame is also a form of social control, and it can be used to punish antisocial behaviour.

"We have this instinct that all shame is bad, but that's way too simplistic," Jacquet said. "Shame could be used to address large-scale social problems."