Coronavirus-hit London’s horrible history of plagues, death and disease

- Before Covid-19 there was Spanish Flu and Black Death

As London braces for more Covid-19 cases – the population confined to their homes, commerce ground to a halt, hospitals at the ready – it is somewhat comforting to know London has survived far worse pandemics before, with much less medical knowledge and equipment.

I used my daily exercise outing under quarantine regulations to enjoy the blissful silence that has befallen the city and go on a cycle tour of three important historical sites of past plagues, all within less than a mile of my home.

My first stop is the church of St Augustine with St Philip’s opposite the blue shiny Royal London Building in Whitechapel in East London, now a hospital museum.

Once known as the Cathedral of the East End, the church contains the only monument in the country to the victims of the so-called Spanish Flu of 1918 that swept across the globe killing more than 50 million people, including 220,000 in Britain. At one point, that flu was claiming the lives of 2,500 people a week in central London.

The memorial, in the form of three stained glass windows, one with a graph of the epidemics spike, cannot be seen from outside. I will have to wait until the museum reopens, once the coronavirus lockdown ends.

Spanish Flu targeted teenagers and young adults. Pregnant women were particularly susceptible. It was sometimes known as Blue Death because those stricken could turn blue as they gasped for air as their infected lungs filled with mucus and blood. Then, as now, lockdowns were used as a weapon to fight the terrible disease that killed as many people as four-and-half years of war. So were masks, social distancing and lots of handwashing.

Yet the Spanish Flu epidemic is rarely talked about – and although I had visited the hospital museum several times – had not noticed the memorial.

“It was a different world. I think they faced out that First World War, they came back to this land fit for heroes which it was not, and they faced a pandemic, quietly, by themselves, in people’s homes,” leading virologist Professor John Oxford told podcast by the Wellcome Trust. “There was a memory of it, and thoughtfulness, but they didn’t go around shouting about it.”

One of the rare testimonies of how the disease affected London life was a letter describing what it was like written in 1973 by a certain Robert Swan, who lost his wife and a baby, a brother and his brother’s family in the epidemic.

“The undertakers couldn’t make the coffins quick enough let alone polish them,” he wrote.

“The bodies changed colour so quickly after death they had to be screwed down to await burial. The grave diggers worked from dawn to dusk seven days a week to cope. The smell of those deaths was indescribable. All these setbacks helped to increase and prolong the epidemic, I’m sure.”

Like Boris Johnson, who has tested positive for Covid-19, David Lloyd George, the prime minister at the time of Spanish Flu, contracted that illness.

Despite its name, Spanish Flu did not come from Spain. Because of the war effort, most newspapers in Europe censored, except neutral Spain where newspapers duly reported this new disease.

Initially Asia was blamed for bringing the disease to Europe through the 180,000 members of the Chinese Labour Corps, the poorly paid Chinese recruits who came to help with the war effort from 2016 until the end of conflict.

A survey of CLC death certificates funded by the US Department of Defence and published in January 2016 in the Chinese Journal of Medicine, shows the disease spread weeks later in the Chinese population in Europe among Europeans.

Spanish Flu is more likely to have been transmitted through wild migratory birds to poultry, then to soldiers in a British camp of war in France who brought it back with them from the trenches.

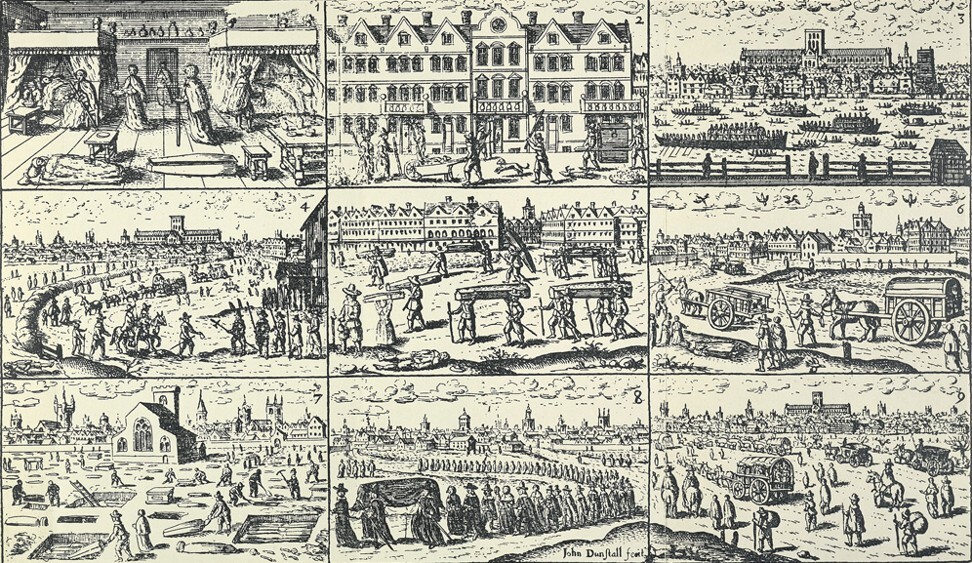

While the Spanish Flu has been largely overlooked by school history books, the Black Death is on every curriculum. The terrible disease swept Europe from 1347, wiping out a third of the continent’s population. Forty per cent of Londoners were killed by it. Images of the grim reaper, cloaked in black, thrilled in Horrible Histories, the British children’s sketch show. We could deal with it because it was something in the past that could not return.

The next stop on my cycle tour, hidden by a long and high brick wall, is one of the largest Black Death plague pits in the city.

The site is known as East Smithfield. Until 1975 it was the home of the Royal Mint, but now belongs to the People’s Republic of China, which bought the leasehold to redevelop for its new embassy and commercial centre in London.

King Edward III, who lost most of his trusted advisers from the plague, seized East Smithfield to build two cemeteries. At the peak of the epidemic, up to 200 bodies were laid to rest there every day.

An excavation in the 1980s of the site uncovered more than 750 skeletons, most of them teenagers or young adults, all victims of the Black Death.

The grass courtyard in front of the main Royal Mint building is thought to still contain the remains of dozens if not hundreds of plague victims.

It is not known if the issue of the mass graveyard will come up in ongoing planning discussions about China’s plans to redevelop the site.

The first recorded Black Death outbreak was in China in 1331. By 1334 the disease killed 5 million in Hubei province, before spreading across the world.

It was thought the disease was spread by fleas jumping from rats to humans, but medical archaeologist Barney Sloane believes it spread far too quickly among humans and could have been another influenza.

It was a terrible disease, causing large painful boils and swelling of the glands, fever and coughing blood. It usually killed in a few days.

The disease hit London twice, the second time was the Great Plague of London in 1665 and is something every child in Britain learns about in school.

It was the last gasp of the original 1300s plague that had made it around the world and back. The 1665 pandemic killed 100,000 Londoners, about one quarter of the city’s population.

“The shrieks of women and children at the windows and doors of their houses, where their dearest relations were perhaps dying, or just dead, were so frequent to be heard as we passed the streets, that it was enough to pierce the stoutest heart in the world to hear them, wrote Daniel Defoe in his 1722 fictional Diary of the Year of the Plague that is nevertheless one of the best descriptions of London then.

“Tears and lamentations were seen almost in every house, especially in the first part of the visitation; for towards the latter end men’s hearts were hardened, and death was so always before their eyes, that they did not so much concern themselves for the loss of their friends, expecting that themselves should be summoned the next hour.”

Lockdowns during the Great Plague involved a red padlock being placed across the door of the house where the disease found, and its inhabitants kept inside under armed guard. A “searcher”, usually a woman, would then go in to hunt for bodies. Whole families died.

It is also remembered for the sinister costumes of the masked doctors of the time with a costume containing leather beak stuffed with herbs. These are still one of the most important costumes of the Venice carnival in Italy that was cut short this year due to the country’s coronavirus outbreak.

One of the first people to warn of the plague’s advance from Amsterdam was the celebrated London diarist Samuel Pepys (1633-1703). Pepys is buried a quarter of a mile away from East Smithfield in the graveyard of the Church of St Olave’s in the City of London. The church dates from the 11th century and is one of the only ones of this period in the city to have survived both the Great Fire and the Blitz.

It is celebrated for the carved skulls above its portico dating from before the Great Plague, which claimed 365 of its congregation, leading writer Charles Dickens to refer to it as Saint Ghastly Grim church.

It’s one of those places I’ve been meaning to visit for years, but have been put off by the pollution and crowds. With the streets empty, it seems almost wondrous now, so old, a reminder of pandemic in the heart of the City of London.

Peering through the locked gate, with three carved skulls above my head, you could imagine the old Pepys chuckling after a verse credited to him went viral on Twitter earlier this month.

“On hearing ill rumour that Londoners may soon be urged into their lodgings by Her Majesty’s men, I looked upon the street to see a gaggle of striplings making fair merry, and no doubt spreading the plague well about,” he was reported to have written at the time of the Great Plague of London.

“Not a care had these rogues for the health of their elders!”

It later emerged the verse was a parody, a modern urban myth.

Hilary Clarke is a freelance journalist in London who writes for the South China Morning Post.