Amsterdam property market draws new money

Property prices in the city have surpassed their height before the 2008 Global Financial Crisis

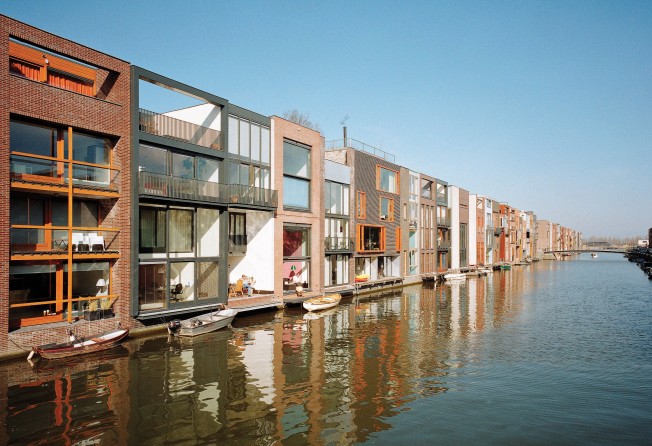

There are plenty of reasons Amsterdam is consistently ranked as one of the world’s best places to live. A boat tour through Amsterdam on a wooden river launch will take you on a gentle journey through the Dutch capital’s tree-lined canals, past the stone-fronted mansions and decorative brick facades from the 19th century.

Last year, 143 foreign firms made the move to the Dutch capital and its surrounding areas. English is widely spoken, perhaps more so than in any other continental European capital. Like Dublin and Berlin, Amsterdam also enjoys the favours of the tech industry; Uber, Netflix and Amazon all have headquarters in the city.

Property prices in Amsterdam have finally surpassed their height before the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, rising 25 per cent since 2013. Figures from CBS, the national statistics office, show that the average asking price for a home in Amsterdam is now €506,000 (US$623,558). Tiny flats in the 19th century areas west and east of the old city, districts once considered beyond the pale, are changing hands for prices nearing €400,000.

Demand is rising, but supply is not keeping pace, thanks to careful price control mechanisms. So-called social housing is a dominant factor. Some 60 per cent of the city’s housing stock is rent-controlled, comprising homes with a rent of up to €710 a month.

This squeeze on what are known as “free sector” homes – flats outside the social sector – means that teachers, policemen and nurses are being pushed out. Developers have therefore been given the green light to build large complexes of small flats aimed at young professionals, complete with gyms, cafes and state-of-the-art Wi-fi – often in prime locations.

“We want to create a mixed city, where poor and rich live side by side and that is a deliberate part of our policy,” said Lex Brans, the city’s director of real estate marketing. “We don’t want homes where rents are too high. Amsterdam must remain an inclusive city.”

We want to create a mixed city, where poor and rich live side by side and that is a deliberate part of our policy

City development guidelines state that 40 per cent of new properties must fall into the social housing sector, a further 40 per cent must be what is known as middle income properties – up to around €1,200 to rent – and the rest, just 20 per cent, is for owner occupiers or private investors. These rigorous rules, implemented in 2017, have been made possible by the fact that the city itself owns most of the land – leasehold is extremely common. The skyline remains quite low, thanks to rules banning buildings of over 60 metres in many areas.

“Building is going on but it is too late and not enough,” said Mie-Lan Kok, a city estate agent who specialises in helping expats buy a home. “People really like living in Amsterdam and when you compare it to other cities, it is still relatively cheap.”

“Some 80 per cent of homes within the Amsterdam ring road are smaller than 80 square metres, and there are very few family homes,” said Sven Heinen, chairman of the Amsterdam real estate agents’ association, MVA.

“If you are looking for three or four bedrooms you are looking for at least 120 sq m and more … then you are looking at upwards of €1 million.”

Homes at the top end – the hidden gems – get sold in secret for sums of €6 million and higher, often to celebrities or top-level executives.

Luckily for them, Amsterdammers like privacy.

“People with homes in the most expensive segments don’t want it to be known that their property is up for sale,” said Marianne Joanknecht, a broker with Sotheby’s International.

(This an excerpt of an article that appears in the March issue of The Peak magazine, available this week at selected bookstores and by invitation.)