Even Tiger Woods could not make golf profitable, says co-founder of Nike

Phil Knight, the co-founder of Nike, was so enamoured with a young Tiger Woods that the company began recruiting him three years before signing him to an endorsement deal at 20.

“You could see him coming from way back,” Knight said in an interview on Bloomberg Television that airs on Wednesday at 9 pm EDT (9 am HK time). The young golfer would occasionally play in the Portland area, near Nike’s headquarters, “and we’d always invite him and his father out to lunch.”

It was the start of a long and ultimately unprofitable relationship.

Woods went on to become the greatest golfer of his generation, and Nike sought to benefit by selling clubs and equipment. But even the celebrity of Woods and his legion of fans weren’t enough to make it break even, said Knight, who left the company’s board last year. Nike exited the category a year ago amid Woods’s fading star power and the sport’s declining popularity.

“It’s a fairly simple equation, that we lost money for 20 years on equipment and balls,” Knight said. “We realised next year wasn’t going to be any different.”

The foray into golf clubs was a failure eclipsed by Nike’s many successes under Knight, who was chief executive officer until 2004 and remained chairman until last year. The company went public in 1980 and emerged as the world’s largest athletic brand. Now it’s working to revive growth under CEO Mark Parker, who will deliver Nike’s latest quarterly earnings on Thursday.

During an expansive interview that ranged from his upbringing to his current focus on philanthropy, the 79-year-old Knight described his start selling shoes out of the trunk of a green Valiant at track meets. He dubbed the company’s transformation to a multinational behemoth his “work of art” and said the greatest skill he learned along the way was the ability to evaluate people.

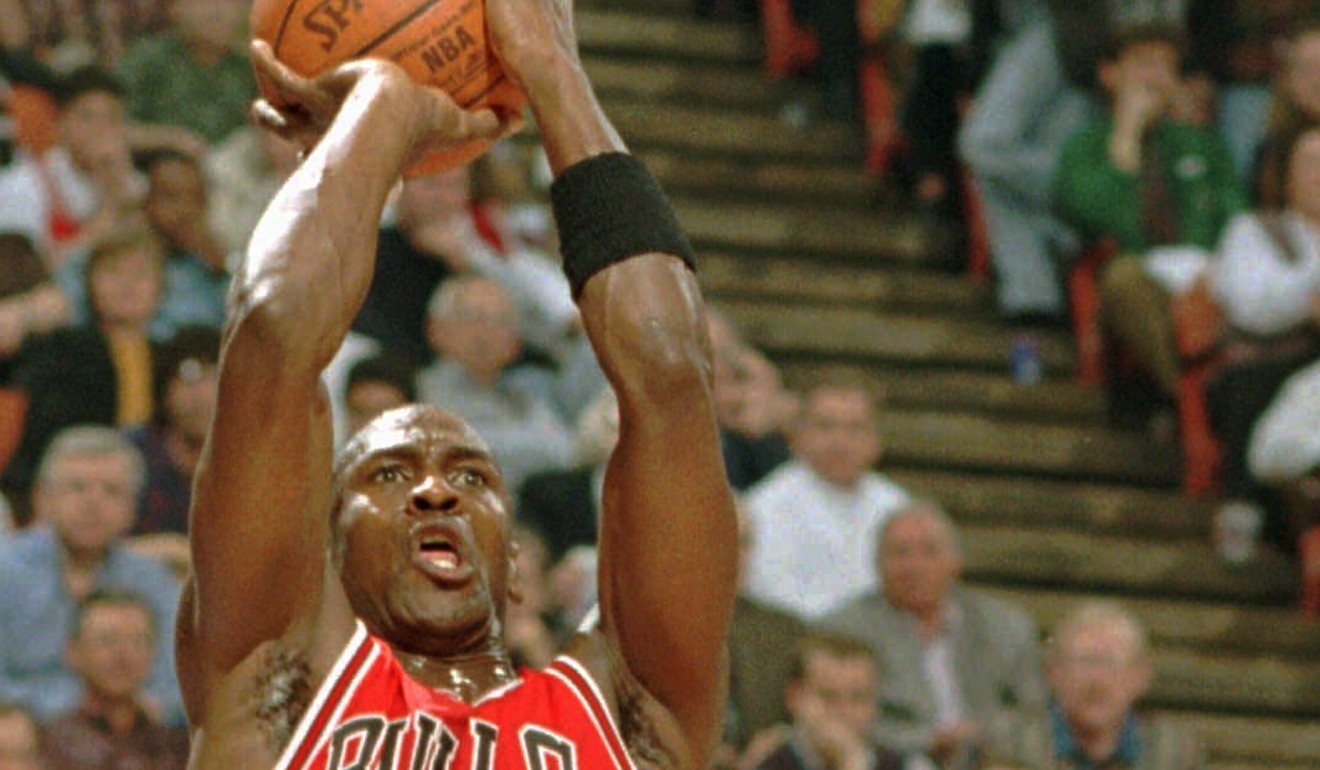

He also gave credit to Michael Jordan, who came along before Nike had built a roster of superstar athlete endorsers.

“We had a lot of good players, we didn’t have really great players,” Knight said. “And we thought he had the chance to be that. He was obviously way better than we ever could have imagined.”

Luck also played a role in Nike’s rise: Sales got a boost after NBA commissioner David Stern ruled that the Air Jordans violated league rules.

“David Stern did us a huge favour. He banned it in the NBA,” Knight said. “And so we ran a big ad that says, ‘Banned in the NBA.’ And every kid wanted the shoe then.”

The Jordan brand is approaching US$3 billion in sales annually and still dominates the basketball shoe market despite the Hall of Famer’s retirement in 2003.

Today, “some kids don’t even know who he was,” Knight said. “It just became a brand. It went from an endorsement into a brand.”

Knight also sees manufacturing returning to the US in the not too distant future, but without much of a job boost. Nike has been investing heavily in improving automation to reduce costs and speed up production.

“The manufacturing technology is changing very, very rapidly,” he said. “So out there somewhere, five or 10 years, there will be some shoe manufacturing done in the United States, which is I suppose the good news. The bad news is, there won’t be a lot of jobs. It’ll be very automated.”