Bruce Lee and the Hong Kong fights that helped shape modern MMA

- Relive the time thousands travelled from Hong Kong to Macau to watch a ‘death duel’

- First martial arts ‘super fight’ gave rise to Bruce Lee’s interest in free-form combat

A long-forgotten series of fights captured the Hong Kong public’s imagination during the nascent days of mixed martial arts. On reflection, and upon investigation, these fights each marked seminal moments in the sport’s development, as MMA evolved from the fringes of society to the global phenomenon that it is today.

Here we remember three bouts that helped shift combat sports towards the birth of modern MMA.

The first was a money-raising charity extravaganza. Hyped as a “death duel” but actually nothing of the sort, it reignited interest in martial arts that had sat dormant, by both fate and by design, for decades, and it inspired a generation of young martial artists that included Bruce Lee.

We look at the only time the “Little Dragon” fought, officially. It was a bout that turned Lee’s head, when it came to the restrictions laid out by rules and regulations.

And then we look at a clash that brought Hong Kong to a standstill, with rumours of millions of dollars gambled. It gave promoters and fighters a taste of what could be achieved.

Was this the world’s first MMA bout?

Wu Gongyi (tai chi) vs Chen Kefu (white crane kung fu)

Date: January 17, 1954

Venue: Macau

It’s been 65 years since this “death duel” held Hong Kong in its grip. It was the biggest martial arts fight promotion that had ever been staged. It held Hong Kong in raptures and, if you follow the thread closely, it inspired a generation to turn to combat sports and, eventually, led directly to the major fight promotions that are sweeping the world today.

When Wu Gongyi and Chen Kefu met to fight in a makeshift outdoor arena in Macau on January 17, 1954 the media attention was frenzied, with the South China Morning Post, among other outlets, latching on to the rumour that there was only one way this was going to end, and labelling the bout a “death duel”.

“True or false, we didn’t really care. It was the most exciting thing we had heard of,” says 85-year-old Wai Kee Shun, a young man at the time, and just starting a career in administration that would shape sports in Hong Kong for decades.

The lead up had been high on drama, with Wu – a 53-year-old tai chi master – issuing a call that he would take on all comers. Rising to the challenge was Chen, at 34 years old a master of white crane kung fu, who had dabbled in other combat sports, and a man who had apparently fled the mainland for Hong Kong after beating up an opponent with government connections.

No matter the age difference, or that of size, the Hong Kong press pack swooped on the event and in grainy archival footage we can still today witness two men wildly mismatched in terms of size and in commitment to the battle at hand. But fight promotions then were as they are today – mostly about the noise that can be generated. And the money.

At its heart, this “death duel” had an almost divine purpose. Less than a month before – on Christmas Eve, a fire had raged through the Shek Kip Mei squatter village in Hong Kong, leaving around 50,000 homeless. Funds needed to be raised and so the idea came about that the bout would be held for charity.

Hong Kong was a no-go, with a conservative colonial government that had banned most forms of combat sport apart from Western-style boxing, and the image of martial arts still tainted from a seedy underworld reputation that dated right back to the ill-fated Boxer Rebellion of 1900.

“Learning martial arts then was very much something you did in private. The reputation wasn’t very good,” explains Wai, who was born into a family of 24 siblings who had all been schooled by one of the disciples of the legendary martial artist and all-round hero Wong Fei-hung.

Macau, long a place where rules considered normal elsewhere did not apply, took up the option of staging the event. To young men of the time, the excitement was seductive. In the weeks leading up to the fight it was all anyone wanted to talk about.

“Everyone was caught up in the hype,” recalls future Hong Kong policeman James Elms, who would also go on to form the city’s groundbreaking Full Contact Boxing promotion with Wai in the early 1980s.

“No matter how ‘real’ the fight was ever going to be, once you heard it was a duel to the death you were sold.”

That was no doubt the case with Bruce Lee, too. At that stage Lee was just 14 years old but already running with street gangs and constantly on the lookout for a fight. It wouldn’t be long, either, before the martial arts trained Lee was expanding his own horizons, too, trying his hand at Western-style boxing as a schoolboy just three years later, in the only officially sanctioned fight the martial arts hero ever had – against a certain Gary Elms, cousin of James.

An estimated 9,000 people eventually gathered in Macau for the bout, with most taking the four-hour ferry trip across the Pearl River Delta from Hong Kong. It was – via newspaper reports, and as witnessed via old film stock – a bit of a farce.

Part punch-up, part pat-a-cake, the upstart Chen knocked old Wu about early before both fighters moved around doing not much at all and the judges called it a draw after less than two rounds, or about four minutes of action.

No matter, though. Reports at the time said 40 per cent of all takings went to those affected by the squatter village blaze, 40 per cent went to Macau’s Kiang Wu Hospital, and 20 per cent went to Macau’s Tung Sin Tong charity. As much as HK$200,000 had been raised – and that hype had sold plenty of newspapers.

After an age in the shadows martial arts was back in the public eye.

“I guess you could say it was a draw but everybody won,” says James Elms. “It was the start of a change in mindset, I suppose. Young boys wanted to learn martial arts, and the money men started to see there was a future in promotion martial arts fights.”

Uncovering the only official fight Bruce Lee ever had

Bruce Lee (challenger, St Francis Xavier School) vs Gary Elms (champion, King George V School)

Date: March 29, 1958

Venue: St George’s School gymnasium

Bruce Lee had priors with those pesky boys from King George V School.

As a wayward Hong Kong youth, Lee had attended La Salle College and had established a reputation as either a bully or a protector of the weak, depending on which camp you sat in. Along with his mates from around Kowloon he would sometimes go looking for British or expat boys who attended KGV to engage them in battle. Or simply just beat them up.

Martial arts were on the rebound in Hong Kong, having fallen out of favour over the previous decades due to government bans on the staging of any other public fights outside Western-style boxing, and a general perception that they were pastimes for characters of ill repute.

But a few years earlier the staging of the “death duel” in Macau had brought combat sports back into the newspapers and while the event in the end was more staged for charity than a real fight, it had nevertheless sparked interest once again in the skills – and maybe even the fame – martial arts could reward those who mastered them.

By the time Lee was 17 – having by this stage been shown the door at La Salle and having taken his talents to St Francis Xavier’s College – it would have been impossible for the young fighter to resist the offer to meet a KGV kid for an approved boxing bout. This was, after all, a young man who had already firmly established a reputation for a willingness to take on all comers.

And that is how the lives of Bruce Lee and Gary Elms converged on March 29, 1958. One young man’s life was destined for superstardom, for fame and fortune and for a tragically early end; the other’s for relative anonymity.

For years there was some dispute as to whether the fight actually took place, with disputes raging across internet chat rooms, but in time the facts have emerged, as have witnesses to the event.

The bout was staged inside the St George’s School gymnasium, with Lee part of a three-strong St Francis Xavier’s squad and the 17-year-old Elms representing KGV having won the title in his weight class the past three tournaments. The result – unanimous victory to Lee after three rounds – is confirmed through newspaper clippings passed over to the Post by Elms’ family.

It was apparently a scrappy fight with Lee struggling to adapt his kung fu skills to Western boxing rules and Elms trying to ward off a style of attack he likely would never have experienced before. It was the only bout won by St Francis Xavier’s College on the 19-fight card.

Much of what we know about the fight itself comes from the extensive research American author Matthew Polly put in to his enlightening biography Bruce Lee: A Life, released last year around the 45th anniversary of Lee’s death.

Classmates are quoted as describing Elms as “one tough nut” but he was apparently no match for Lee, by that stage of his life already deep into his wing chun kung fu training. There were a few knock-downs but no knockout, something Lee later blamed on the size of the regulation gloves which he claimed softened his blows.

It would be the only officially recognised and judged fight that Lee would have, preferring afterwards to focus more fully on his martial arts training under the tutelage of masters Ip Man and Wong Shun Leung. There continued to be street fights and, as his star rose, Lee was sometimes called out by young guns wanting to make a name for themselves against the hardest man in town. But these were all fought in secret.

Lee left St George’s gymnasium vowing to expand his skill set, beginning a journey of exploration that would see him develop his own style of jeet kune do kung fu while exploring all manner of combat sports and encouraging his students to do the same. Such a philosophy would much later inspire the emergence of mixed martial arts (MMA) – a sport that considers Lee its “grandfather.”

Gary Elms’ passion for combat sports obviously burned deep in his family, with his cousin James Elms later becoming one of the founders of Hong Kong’s Full Contact Boxing promotion, itself also a precursor to the rise of MMA.

And while the rest of Lee’s life played out publicly, Gary Elms’ journey took him travelling around the world, from Australia to Africa, before he passed away in the United Kingdom on January 1, last year, aged 78.

“Gary did exist and the fight with Bruce Lee did happen but Gary was not a professional boxer,” Elms’ sister Lorraine Barclay tells the Post. “Gary was an amazing person, he was soft-spoken, a great debater, well-read and knowledgeable in many fields, he was honest and played fair. He was a loner, loved nature. There is no one that I know of that has a nasty thing to say about Gary. In fact they say they wished they had more time with Gary – he was an interesting man.”

The fight that brought Hong Kong to a standstill

Kong Fu-tak vs Billy Chow

Date: June 27, 1983

Venue: QEII Stadium

Kong Fu-tak believes he was born to fight and he’s done a decent job since his youngest days of trying to turn that theory into fact.

Combat sports ruled the Hong Kong scene for an all-too-brief few years from the early 1980s, mostly under the Full Contact Boxing promotional banner, and Kong was among its brightest stars.

Fight nights were held two to three times a month with full houses greeting local and international fighters at the likes of the QEII and Southorn stadiums, and with unique rules set by the Full Contact Boxing Referees Association allowing combatants to mix martial arts styles in what was a precursor to the sort of fights now held by MMA organisations the whole world over.

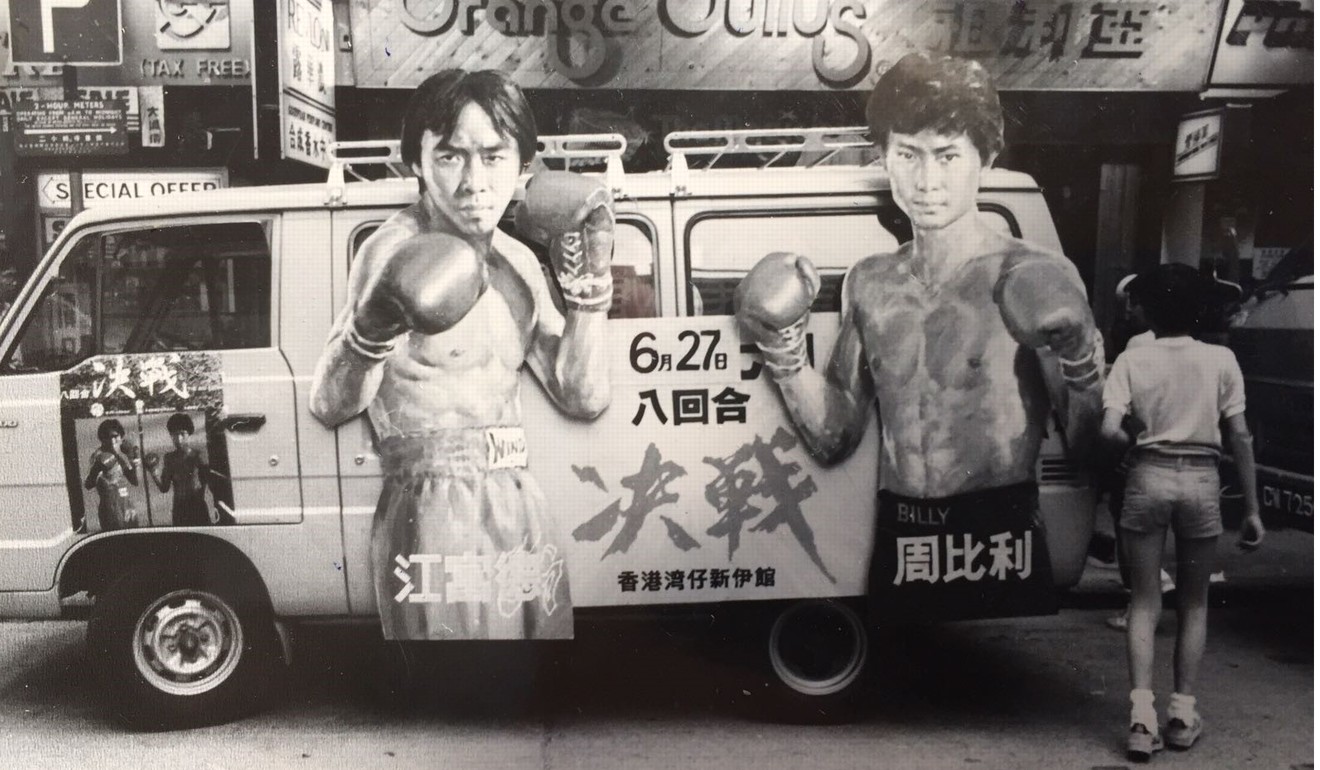

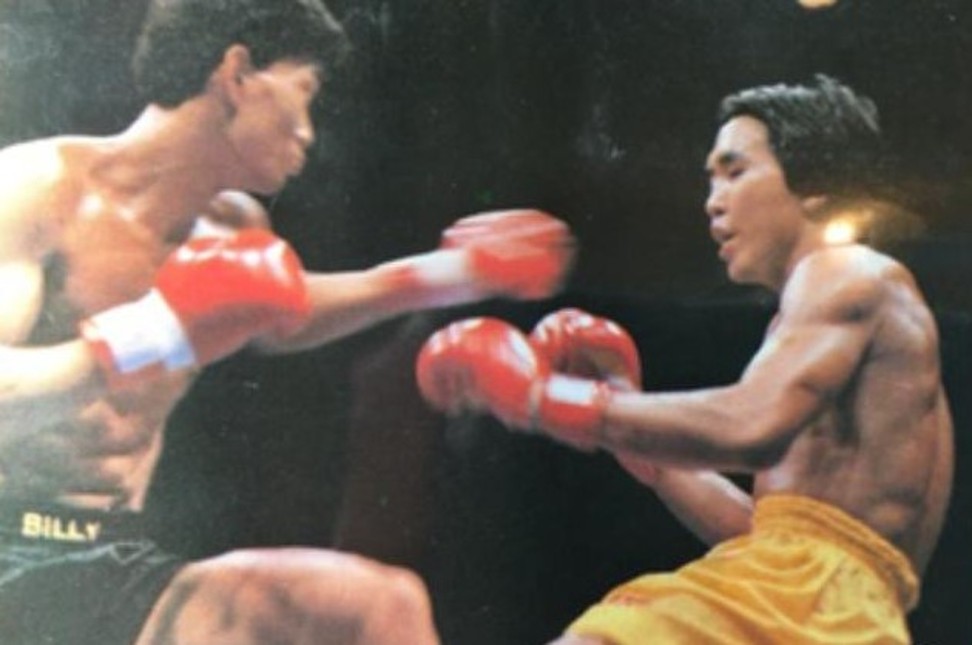

It gave warriors such as Kong the chance to fight how they liked, against who they liked, and never was there a bigger night for martial arts in Hong Kong than June 27, 1983 at an overflowing QEII Stadium, when Kong faced down Billy Chow, world welterweight kick-boxing champion and soon-to-be movie star.

The rules were laid out to follow those of Muay Thai, with a little leeway given, and the round count was set for eight instead of the usual five-round limit.

“It was known as the fight of the century,” says the now 62-year-old Kong. “[Full Contact Boxing founders James Elms and Wai Kee-shun] saw me as a young man with a fighting spirit. They were supportive and gave me a lot of encouragement. I fought many times. Billy Chow was the most famous fighter in Canada and I was known as “Kung Fu” Tak in Hong Kong. That event is still seen as a game changer.”

Kong had been a scrapper on the streets of Kowloon as a young man, hiding his karate and kung fu lessons from a family that didn’t really approve before being packed off to London to find work and focus. He did both, but the latter came through learning more martial arts and he returned to Hong Kong a Muay Thai champion. Soon he would be facing the legendary American full contact karate and kick-boxing champion Benny “The Jet” Urquidez in a brutal bout that Kong lost via fourth-round TKO (cut) but that established him as the leading martial artist of his generation.

Chow had meanwhile emerged out of Canada with that world kick-boxing title as well as skills developed through Muay Thai and Western boxing. Such was his flair, that the Hong Kong film industry would soon turn his way with the likes of martial arts masters Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung Kam-bo helping to transform Chow into an action star with a hard edge forged in real combat.

In the lead up to the bout there was blanket media coverage, with TV talk shows focusing on who might win and how, while the tabloids focused on the rumours of side bets said to be climbing into the tens of millions of dollars. There were vans patrolling the streets with images of the fighters on their sides, and loudspeakers urging the public to come see the show. There was also the matter of the triads.

“Some of my colleagues told me we had about three or four dragon heads [triad leaders] there,” recalls James Elms who, outside the fight game, worked as a policeman. “I heard the side bets ran into the tens of millions of dollars.”

“It was tough and Billy Chow was a master fighter,” says Kong. “We both hurt each other many times but there was no chance we would give up with so much at stake. If you see the video you can see we are exhausted by the end. It is still the proudest moment in my life.”

Kong’s armed was raised with the referees handing him the unanimous decision.

“When the decision was made there wasn’t any knife throwing or any shots fired. Everybody took it quietly,” recalls Elms. “Maybe the fact that it was made by cops had something to do with it ...”

Chow kept accepting bouts until 2007. After a successful movie career in Hong Kong from 1984 to 2006 – with roles in around 70 films – he returned to Canada and now splits his time between his gyms both there and in Hong Kong.

Kong kept fighting until the end of the ’80s and when the Full Contact Boxing organisation closed – under pressure from a government that refused to sanctify its rules set – he also turned to coaching, opening a string of Fu Tak Thaiboxing and Fitness schools across Greater China. He estimated he has coached around 100,000 fighters in the decades since those heady days – and nights.

“I want to cultivate generations after generation of fighters,” says Kong. “I want them to fight for their honour and for their ideals.”