Bike-sharing craze gives Phoenix new lease of life – but what’s next for the 120-year-old bike maker?

China’s dockless bike-sharing craze has rejuvenated the fortunes of the humble bicycle, but can manufacturers like Shanghai Phoenix build a sustainable future?

Owning a bicycle in the 1950s and 1960s was the ultimate status symbol in China for the average family. A bicycle then cost a worker three to four months in wages and the most coveted was the “Big 28", named after the sturdy 28-inch wheels that allowed this particular model to transport a family of three comfortably down the road.

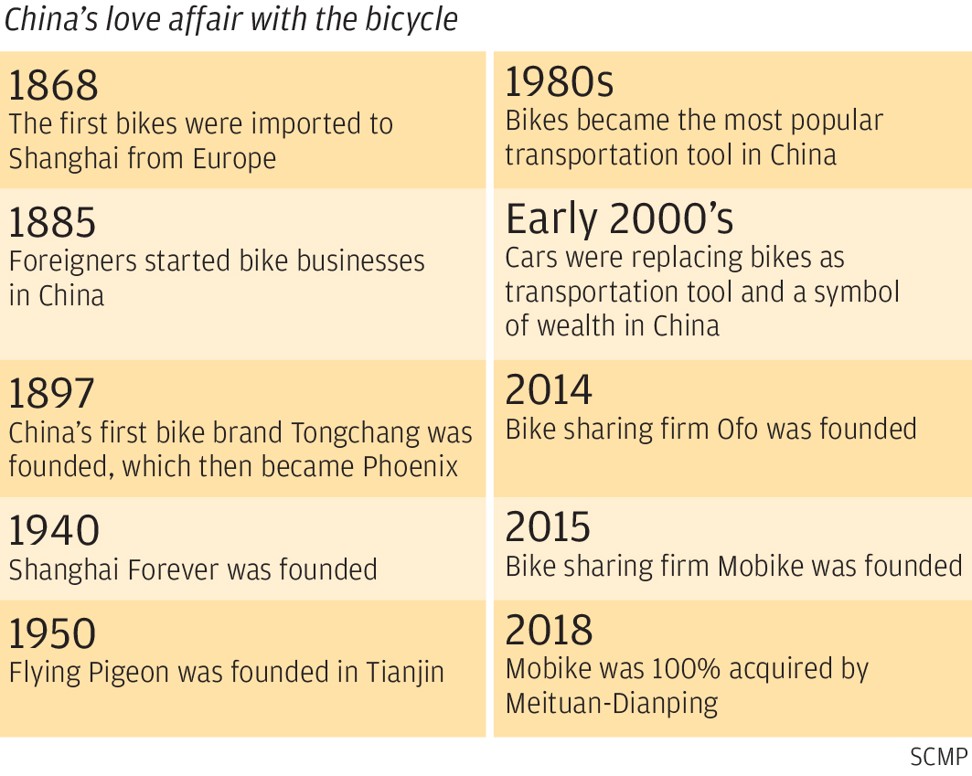

And among the most famous brands was Shanghai Phoenix, which has been manufacturing bicycles in China since being founded in 1897. Phoenix resonates in China like Raleigh does in the UK or Schwinn in the US. It was such a prestigious brand in its heyday that many took to counterfeiting its bikes – just as you can find fake Rolex watches today.

Phoenix traces its beginnings back to 1897, when its predecessor Tongchang Bicycle was founded. In 1959, the Tongchang name was changed to Phoenix. Unlike the mythological bird of ancient Egypt and classical antiquity, which consumes itself by fire and is reborn from the pyre, the Chinese phoenix – known as fenghuang – is a symbol of virtue and grace and is traditionally paired with the dragon in Chinese culture.

Eight years ago, as part of an ownership restructuring, the then solely state-owned Phoenix welcomed a private investor, Jiangsu Meile. The holding company, which is listed in Shanghai, still counts a district government of the mega-city as its largest shareholder. Even though Phoenix is based in Shanghai, its main factories are in Jiangsu and in Tianjin, which produces 40 per cent of the world’s bicycles.

For Wang Chaoyang, the 53-year-old president of Phoenix Bicycles, the company’s legacy is both a blessing and a burden.

A blessing because the Phoenix brand heritage is well-known nationally, particularly among the elderly. A burden because the younger generation no longer sees the bicycle as integral to their lives, now that cars, buses and the subway have replaced the traditional two-wheeler as the main mode of transport in China’s mega cities.

“Phoenix as a brand still has cachet among the elderly, but for the 20-somethings it’s still a work in progress,” Wang said. “Brand awareness is high, but brand understanding is low.”

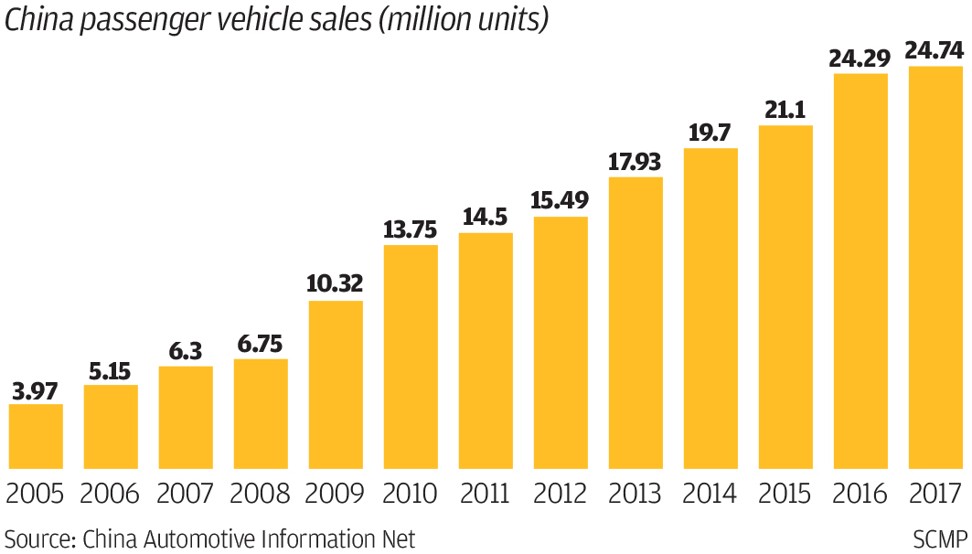

The number of bicycles in use in China fell from 670 million in 1995 to 370 million in 2013. Conversely, the number of passenger vehicles topped 300 million last year, from zero in 1978 and consumers bought almost 25 million new vehicles in China last year. The car, together with an apartment and bank account, have become the new “Big Three” for a Chinese couple to get married. This compares with the 1980s and 90s when the “Big Three” consumer items were a bicycle, a watch and a sewing machine.

However, this rather bleak picture has brightened after a recent surge in popularity in China for dockless bike-sharing, which has given the humble bicycle a new lease of life as an environmentally-friendly means of transporting commuters over the last mile of their journey. Manufacturers like Phoenix suddenly received a flood of orders from bike-sharing start-ups, giving them the scale to increase and upgrade their manufacturing capacity and technology.

Orders from Ofo, the Beijing-based sharing start-up with distinctive bright yellow bicycles, contributed 600 million yuan (US$94 million) of orders last year, or 42 per cent of Phoenix’s total revenue. Wang's biggest worry however, is how to use this welcome momentum – and cash – to recast Phoenix as a lifestyle brand relevant to today's consumers.

“We’ve taken advantage of this new-found passion for a sharing economy,” Wang said in a recent interview at the company’s headquarters in a Shanghai suburb. “We’re not saints and want to do the easy thing and last year, the easiest thing to do was to be involved in the sharing boom.”

There is concern though that an over-reliance on bike-sharing may set bicycle manufacturers up for a boom-and-bust cycle, should the phenomenon prove to be a fad. At the peak of the boom, there were more than 30 bike-sharing brands in the market, piling millions of new bicycles onto roads and pavements, crowding out pedestrians and cars. Thousands of bicycles were found abandoned in empty fields, streams and even hanging on trees.

According to China’s transport authority, cutthroat competition for market share led to an estimated 16 million rental bicycles in Chinese cities by September 2017, and their ride-anywhere and park-anywhere business models were becoming “an unsightly public nuisance” despite the last-mile convenience provided to city commuters.

As a result, dozens of Chinese cities including Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen have barred the country’s more than 70 rental companies from putting more new bikes on the streets. This has led to industry consolidation with Beijing-based Mobike, which was acquired by Meituan-Dianping in April, squaring off with Ofo and Hellobike for market leadership. However, no bike-sharing start-up has yet to turn a profit.

“Bike-sharing has pushed the industry forward and helped manufacturers improve their technical ability, such as anti-rust and anti-theft features,” said Wang. “But we want to see how this resurgent demand drives future change, prepare in advance for it and seize the business opportunities in a good way,” he said.

“The margins for bike makers producing bikes for sharing platforms are quite thin and the only way to expand profits is to grow volume,” said Sun Naiyue, analyst at Chinese research firm Canalysys, nothing that the crackdown by local government on new bikes would be an obstacle. Ofo, for example, recently said it only took up 37 per cent of an original bike purchase order with Phoenix.

Shanghai Phoenix Bicycles is a subsidiary of Shanghai Phoenix Enterprise Group. Shares in the parent group are down about 20 per cent this year, versus a 4.7 per cent drop in the Shanghai Composite Index.

For Phoenix, people in their 40s and 50s – who are familiar with the firm’s heritage – could be a target as they can be persuaded to buy bikes for their children and grand children, or their elders, Wang said. The decision to move into children’s products was also prompted by the gradual relaxation of China’s one-child policy, which is expected to boost the number of babies and demand for related products in the years to come.

Although Africa used to be its biggest export market, today the continent accounts for less than 10 per cent of sales. Asia is now the biggest export market, followed by Eastern Europe, South America and Latin America.

There is also the question of brand: consumers only care about the sharing company and not the manufacturer, according to Xue Yu, an analyst at research firm IDC. “The needs of people using bike-sharing platforms are directly satisfied by the platform, they do not pay much attention to who made the bike itself,” said Xue.

Wang vows that Phoenix will walk with two legs and won't let the ‘bike sharing leg’ drown out the company’s own ‘brand leg’.

“I hope that bike sharing will continue to develop in a healthy way because it’s already a crucial part of the industry,” Wang said. “If they don’t exist anymore, we won’t have a future either.”

“But a brand cannot be built in a year,” Wang said. “The brand that is built up the fastest can also collapse the fastest too.”

Wang says he asks himself the same question every night before he goes to sleep – will he be able to correctly judge the direction of the industry in future and how many of his decisions will be proven right.

But for Wang, there’s no turning back.

“People in our industry understand that bikes only move forward when you ride them. If you stop, they fall down,” said Wang said. “That’s why you always have to move forward.”