China’s semiconductors: How Wuhan’s challenger to Chinese chip champion SMIC turned from dream to nightmare

- Hopes that the HSMC facility could still proceed faded after more than 240 employees were asked to resign by March 5

- The failure of HSMC was a setback but it won’t deter China’s push for self-sufficiency in chips, according to analysts

When Cao Shan promised he could build a chip plant to challenge China’s reigning chip champion, Shanghai-based Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), the Wuhan local government was quick to jump on board.

The promises of semiconductor glory were music to the ears of local authorities that had been trying to claim the high ground in China’s burgeoning semiconductor manufacturing industry. Their dream of claiming the number one spot, however, has over the past 12 months turned into a “nightmare” of unfulfilled promises.

On a rainy and windy Friday afternoon this month, the Hongxin Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (HSMC) campus in Wuhan was empty and silent. The difference from pre-pandemic times in late 2019 could not be more striking. “The streets were very crowded, full of all kinds of food stalls and all parking spaces were full,” a former HSMC employee told the South China Morning Post.

But it was not the pandemic that killed HSMC, once considered a rising star in China’s chip industry. The project broke ground in the capital city of central China’s Hubei province in early 2018. Backers boasted that the finished plant would produce 30,000 wafers a month, using advanced 14 nanometre technology for chips used in smartphones and smart cars, according to a cached version of the company’s now inactive website.

Three years after its birth, the pride turned to humiliation as the whole project was revealed to be built on broken promises, the latest in a string of scandals along China’s long road to chip autonomy, according to reporting by the Post based on visits to the campus, interviews with HSMC employees and its former chief executive, and a review of local media reports and government documents.

Cao and the other senior executives behind HSMC have since disappeared. Not a single chip has been produced by the project despite three years of investment. On the Post’s latest visit to the site, there were unfinished buildings with bare bricks and steel bars exposed, as well as prefabricated houses for workers, and wide but empty asphalt roads. The only people visible were some former employees seeking compensation after an abruptly announced dismissal plan.

One HSMC engineer in his 20s, dressed in a white hoodie and a grey jacket, who declined to be named because he signed a non-disclosure agreement, told the Post that he joined the company in 2019 and thought there was a chance the project could go ahead.

“The only thing we lacked was money. It was a really good team. If [the investors] were able to get us the manufacturing equipment, I think we could have started production by now,” he said.

Building an advanced wafer fab of the kind envisaged by HSMC requires billions of US dollars, a highly skilled workforce, and many months of fine tuning the complex chip fabrication process before volume production can be achieved. According to a local government report issued last July, HSMC’s phase one factory, which covered more than 390,000 square metres, was partially completed but needed more capital, and construction of its phase two facility had barely started. As a result, the company was not able to apply for central government funding.

All hopes that the facility could still proceed faded after more than 240 HSMC employees, including the engineer in the hoodie, were asked to resign by March 5. An internal message posted by the company on February 26, and seen by the Post, said it has “no plans to resume work and production”.

After Chinese President Xi Jinping urged the country to reduce reliance on imported hi-tech components, especially semiconductors, the central government rolled out supportive policies, from tax breaks to fiscal subsidies, for new chip projects. As well, city governments across the country rushed to start their own semiconductor projects even though many lacked experience.

“Some local governments that are eager to launch hi-tech projects lack relevant experience and clear understanding of project risks,” said Liu Yushi, senior analyst at Shanghai-based research firm CINNO. “They simply use generous subsidies and large amounts of capital to attract projects. They should deepen their understanding in relevant industries.”

Wuhan, where Covid-19 first struck in China, is an industrial powerhouse known for its steel, semiconductor and automotive industries. The city is home to Wuhan Xinxin Semiconductor Manufacturing Co, memory chip maker Yangtze Memory Technologies Co, and a branch of display panel maker BOE Technology Group.

The failure of HSMC was a setback but it won’t deter China’s push for self-sufficiency in chips, according to analysts. Beijing reiterated its goal to become self-sufficient in the technology in its latest five-year plan for 2021-2025.

“There is a lot of money willing to invest in semiconductors [in China], but whether it can be made the best use of, or invested efficiently, is a big question,” said Roger Sheng, a semiconductor analyst at research firm Gartner.

In 2014, the central government set up the China National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, known as the Big Fund, which has since completed two rounds of financing and raised capital of 138.7 billion yuan and 204.1 billion yuan, respectively. Local governments in China, including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Sichuan, Hubei, Jiangsu and Fujian, have also provided guidance funds totalling more than 300 billion yuan to support their own semiconductor industries, according to public reports.

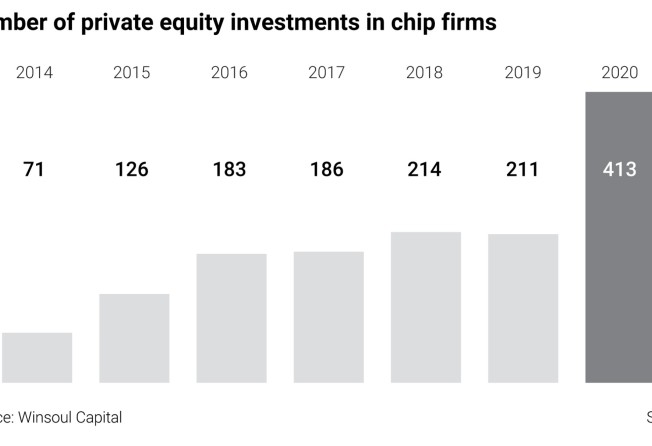

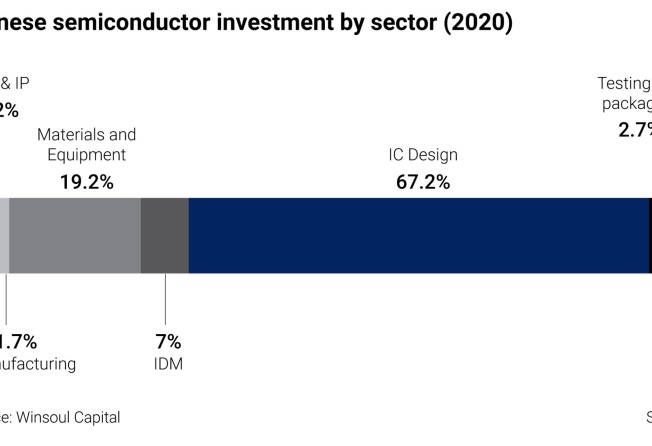

China’s Nasdaq-style Star Market is another funding channel for the chip industry, with the sector accounting for 30 per cent of its total market value, according to Winsoul Capital, a tech investment firm. In the private market, Winsoul said there were 413 semiconductor-related equity investments last year, worth more than 140 billion yuan, a nearly fourfold increase over the previous year.

“I call it an engine and gearbox problem,” said Warren Zhou Hualin, senior investment manager at Decent Capital, a venture capital firm founded by Tencent co-founder Jason Zeng. “Since 2018, large-scale investments in the industry have provided enough energy for the engine, but our gearbox is not good enough … and China is slowly tuning it.”

First announced in November 2017 as part of a local government investment plan, HSMC’s facility would create 50,000 jobs directly or indirectly and have an annual output of 60 billion yuan (US$9.25 billion) once running at full capacity, local authorities said at the time.

The Dongxihu district government put up the initial 200 million yuan investment in HSMC, but the company’s owner – a Beijing based firm – has still not fulfilled its commitment to inject capital of 1.8 billion yuan into the project, according to corporate records.

The first cracks appeared in 2019 when a Wuhan court put a three-year hold on HSMC’s use of 220,000 square metres of land that had been designated for its phase two project. It followed a complaint by a construction contractor who said the chip company and its main contractor still owed it millions of yuan for the first phase of construction.

Regardless, HSMC’s leaders staged a high-profile event in December 2019 to celebrate the purchase of its first piece of high-end equipment: a lithography system from ASML, the Dutch firm that makes the expensive machines that use wavelengths of light to print circuit patterns onto silicon wafers. But HSMC management quickly pledged the new system as collateral to borrow more than 500 million yuan from a local bank.

HSMC scored another coup in 2019 when it recruited industry veteran Chiang Shang-yi as its chief executive. That gave the project instant credibility, as Chiang was once the R&D director at Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s biggest chip foundry. Two ex-HSMC engineers told the Post that they agreed to join the company mainly because of Chiang’s involvement, but soon sensed something was wrong after they heard rumours about funding problems.

On the surface, it all seemed fine. “Before the pandemic hit, over 2,000 workers came in and out every day to build the wafer fab and everything was in full swing. There were people everywhere,” said one of the engineers the Post spoke to. Even after the coronavirus outbreak, HSMC continued to pay staff salaries while other companies in the city were laying people off and cutting salaries during the citywide lockdown from late January to early April.

A major setback came in June when Chiang suddenly announced he was leaving. He later told the Post in a written message that his experience at HSMC was a “nightmare” and that he was unaware of the extent of its financial difficulties until the local government exposed the problem in the July 2020 report.

The HSMC engineer told the Post that despite the rumours and media reports about the company’s funding issues, it was still hiring engineering staff last May and June and employee numbers peaked at more than 400 around that time. The engineer himself was busy through to September of last year, communicating with equipment suppliers in the US, Japan and Singapore.

In December, the HSMC project was taken over by the Wuhan city government, which brought in a new management team. One former employee said the new people were not known in the semiconductor industry.

HSMC may be a high profile failure, but it is not the first case of a poorly planned semiconductor project in China. Earlier last year, a US$100 million plant set up by US chip foundry GlobalFoundries and the Chengdu city government ceased operations after remaining idle for almost two years. In the country’s east, a US$3 billion government-backed chip project owned by Tacoma Nanjing Semiconductor Technology went bankrupt in July after failing to attract investors.

After more than 10 high-profile, government-sponsored semiconductor projects were reported to have gone bust over the past two years, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) said in October that Beijing would strengthen supervision of new entrants into the “chaotic” industry.

Shanghai-based research firm Icwise reported that companies in traditional industries – including some involved in the production of cement, clothing and even decorations – have made high-profile announcements in semiconductor-related projects.

“[The chip industry] is going through a similar path as the solar power and new energy vehicle industries,” said Xu Mengnan, assistant general manager for TMT investment at Hengqin Financial Investment. “In the early stage, there are lots of aggressive investments and support [which lead to] various problems. However, it’s a necessary process for the tide to wash out the sand and leave the gold on the shore.”

As of March 5, most HSMC employees had resigned, receiving one-month’s salary as compensation. The company logos and signage have been taken down, but former employees will likely rebound quickly as chip making expertise is in high demand in China. The first ex-HSMC engineer said he and most former colleagues have already got new job offers.

For the Wuhan government, it has been a painful lesson. “For China’s hi-tech industry, it’s not necessarily a bad thing,” said Zhou from Decent Capital. “HSMC is like a whale. After its death, its corpse – the talent and equipment – will soon be digested by others [in the ocean], so it’s not a waste for the entire ecosystem.”