Chip shortage risks becoming a glut in 2023 as fabs scramble to add capacity, say analysts

- There is potential for overcapacity in 2023 as larger-scale fab expansions come online towards the end of 2022, according to IDC Research

- The semiconductor industry is highly cyclical, running through a peak-to-trough cycle every 4 to 6 years.

As semiconductor foundries scramble to add capacity to meet soaring demand amid a protracted chip shortage, some experts are warning that the demand-supply equilibrium will be reached in 2023, possibly leading to a supply glut down the road.

“Our view is that when we come to 2023, there will be sufficient supply to come back into some degree of balance, or maybe even overcapacity,” Gokul Hariharan, co-head of Asia-Pacific TMT Research at US investment bank J.P. Morgan, said in an interview with the Post, adding that it was too early to predict when the glut would occur.

Hariharan said he does not expect a major downturn in 2023 because “demand is still relatively healthy,” but a 2 per cent revenue decline for the industry is possible.

There is potential for overcapacity in 2023 as “larger-scale capacity expansions begin to come online towards the end of 2022,” according to a report from IDC Research.

These include a new megafab being built in the US state of Arizona by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), and a US$17 billion fab in Texas announced by Samsung Electronics, with production slated to begin in the second half of 2024.

The semiconductor industry is highly cyclical, running through a peak-to-trough cycle every 4 to 6 years. Upturns occur during periods of high demand, which in turn cause supply shortages, leading to higher prices and revenue growth.

However, that is often followed by downturns and inventory build-up, which result in falling prices and negative or zero revenue growth.

For example, the revenue of the top 10 semiconductor firms, including Intel and Samsung Electronics, declined 12 per cent in 2019 due to oversupply in the DRAM market and the US-China trade war, according to Gartner.

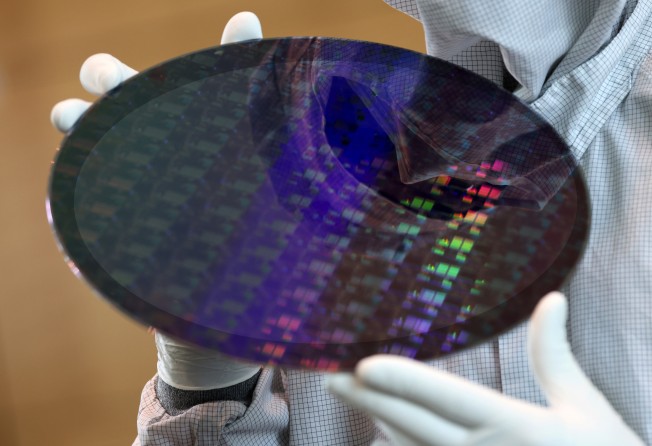

China is also in the expansion game, with its leading foundry Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC) building three 28nm fabs in Beijing, Shenzhen and Shanghai, respectively. The combined capacity of 240,000 12-inch wafers per month will nearly double its current output once volume production is reached in the next three to five years.

Analysts said tightness in the semiconductor supply chain has already begun to ease in China as momentum in sales of smartphones and new energy vehicles, two key end users of chips, has slowed due to weaker consumption.

China’s third-quarter smartphone sales declined 9 per cent year on year to 76.5 million units due to weak consumer demand and component shortages, according to a research note from research firm Counterpoint.

Xie Ruifeng, a senior analyst with Shanghai-based semiconductor consulting firm ICWise, said the semiconductor shortage has eased because smartphone markers slashed chip inventories amid sluggish sales.

Bai Lei, a salesman for a Shanghai-based chip designer, said the tight supply chain situation was alleviated primarily because demand turned soft, not because of new capacity coming online.

The risk, then, is that capacity will exceed demand when the new fabs come online. “Demand for end-user devices is slowing, but that has yet to be transmitted to foundries,” Bai said.