Cars to batteries: is China’s sharing economy in bubble territory?

First it was cars, then it was bikes, now it’s the battery’s turn to transform China’s sharing economy. Some fear that’s a trend too far

Yukin Pang, a public relations specialist in Shenzhen, relies on her iPhone for everything from responding to work emails to paying her taxi bill.

But that frequent use has a side effect that will be familiar to smartphone users worldwide: a short battery life that leaves the 28-year-old fretting about when the next ill-timed power outage will strike.

While she has several battery banks, she rarely carries them, either forgetting to pick them up or leaving them at home due to their bulk and weight. Instead, when she is on the go and her battery runs low, she runs to the nearest restaurant in the hope of borrowing a charger.

That’s a hassle that’s recently disappeared for Pang, who has discovered one of the latest wonders of China’s sharing economy – a battery bank rental service.

“It’s really convenient,” Pang gushes. “I think it’s a great idea, and I have seen many others using the service, too.”

Chinese investors are betting that customers like Pang will help to make battery charging services the next logical step in the sharing economy – following the emergence of ride-hailing apps such as Uber and the seemingly ubiquitous bike-sharing schemes that now exist everywhere from Beijing and Shanghai to Hangzhou (杭州) and Chengdu ( 成都 ).

Since April, Chinese investors have poured at least US$160 million into just 11 startup companies offering pay-as-you-go battery charging services in the belief they will become the next big thing, according to data from online investment database itjuzi.com. One of those companies, Hangzhou-based Xiaodian Technology, was just five months old when it caught the eye of Chinese technology giant Tencent.

“Nowadays, Chinese citizens do not even bother to carry a wallet, they use mobile payments instead. Do you think they would bring their phone battery banks with them while going out?” asks Wilson Shi, a spokesperson for Laidian Technology, one of China’s first battery sharing service providers.

The Shenzhen-based company manufactures its own battery banks, which it distributes in machines across the country, particularly at shopping malls and transport hubs.

A business traveller who is waiting for a train in Shanghai Railway Station, for example, might pick up a portable battery bank from one of its distribution machines by scanning a QR code and paying a small deposit – typically around 100 yuan (HK$110). He then charges his phone during his trip and returns the device to another machine – perhaps once he arrives in Beijing. The recharging costs no more than 10 yuan per day, and all the services are operated via a mobile app.

The company raised US$20 million in April. Shi says it expects to close its second round of fundraising later this month, and is looking to raise at least the same amount again.

Despite the success of companies such as Laidian, some analysts say it is too early to know whether such business models make sense. Others voice a growing concern – that an investment bubble may be fuelling the sharing economy.

The so-called sharing economy – an umbrella term referring to mainly peer-to-peer based sharing of access to goods and services – has seen massive growth in recent years. In 2015 it was worth 1,956 billion yuan (US$283 billion), according to the State Information Centre in Beijing. The country is now sharing pretty much everything, from cars to homes to umbrellas. In Chengdu, a mobile app helps car owners rent out parking spaces during their absence.

According to government projections, the sharing economy will contribute to 10 per cent of China’s economic output by 2020, up from nearly 3 per cent in 2015.

“I see the sharing economy as already having entered a bubble,” says Brock Silvers, managing director at Kaiyuan Capital, a private equity investment firm in Shanghai. “While there may exist a legitimate demand for some level of certain forms of sharing, I simply don’t see that demand warranting the tremendous investment capital inflows.”

Similar opinions abound on social media, where articles foretelling doom for battery bank sharing companies abound.

And despite official policies and rhetoric aimed at boosting the sharing economy, even the government has acknowledged it has not all been plain sailing. According to the State Information Centre, nearly one-third of peer-to-peer lending platforms in China are “problematic”.

It noted in a report that illegal financial services – such as firms offering high-interest loans – had flourished on the internet by touting themselves as part of the sharing economy.

Critics also say China’s sharing economy is, counter-intuitively, contributing to a waste of resources.

Unlike Western companies that have tended to engage in the sharing economy by tapping idle assets, such as couch-surfing sites that make use of empty homes, Chinese counterparts have often needed to invest heavily in purchasing new products.

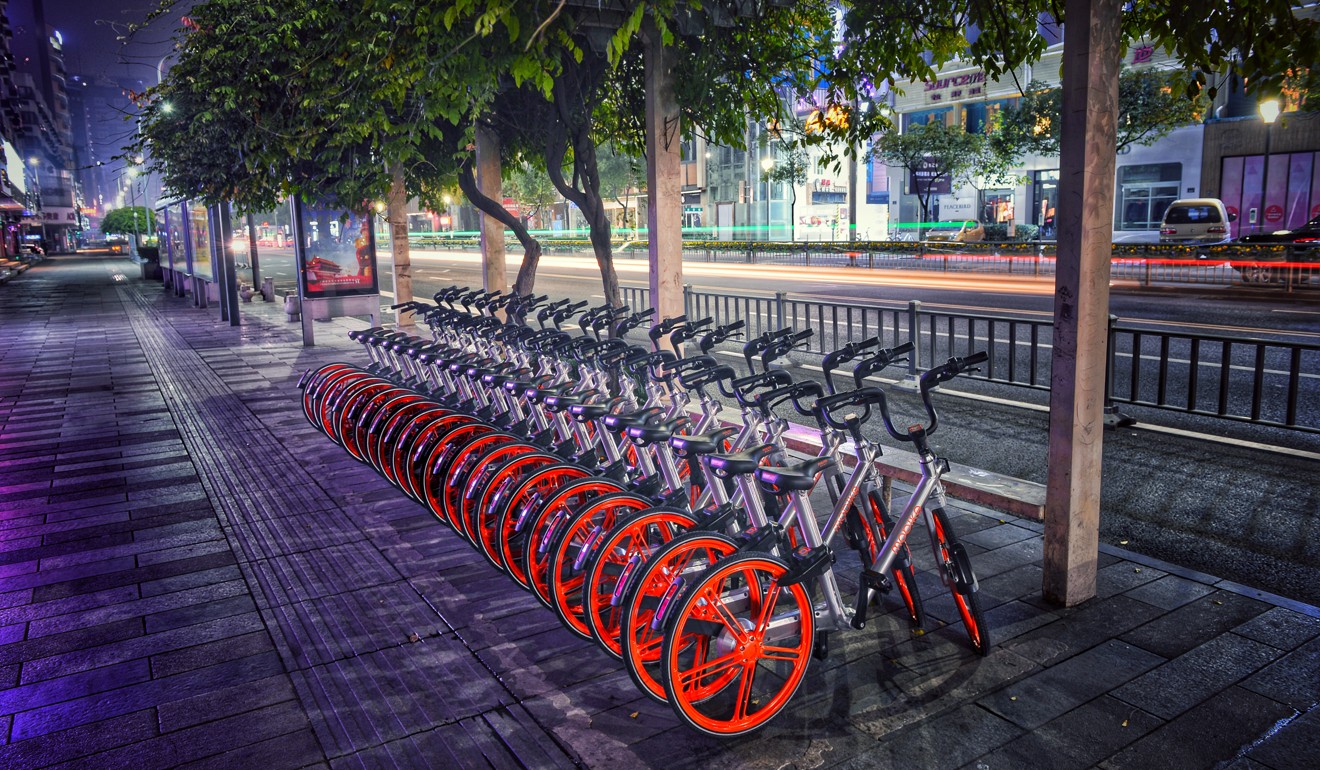

In the bike-sharing sector for example, each competing company has introduced its own fleet of bicycles, leading to scenes in most major cities where street corners are cluttered by row upon row of new bikes.

Raymond Chang, who teaches entrepreneurship at the graduate business school of Yale University, thinks a similar fate might await battery bank sharing. “There will likely be multiple ‘bloodbaths’ among venture capitalists before a real winner emerges,” Chang says. “The shared economy will come, but it will come at a huge cost.”

Indeed, even those businesses benefitting from the craze are expressing concerns.

“For now, the Chinese battery bank sharing sector is in its infancy and has plenty of room to grow. But with too many players entering the sector, we are concerned that there will be an overcapacity issue in the future,” says Shi, of Laidian Technology.

But the three-year-old startup itself has no plans to halt expansion. Shi says it will install more than one million battery bank distribution machines by the end of 2017, up from some 2,000 machines at present.

Once Chinese become used to using public battery banks to recharge their devices, they will no longer feel the need to purchase their own, according to Shi: “Our service helps save money and maximise resources.”

Analysts and environmentalists may be unconvinced as yet, but Pang, the Shenzhen PR worker, is convinced of the difference it has made to her life.

She seems surprised when asked if she thinks there is an investment bubble in China’s sharing economy. “I think there are not enough places offering such a service. If it is a bubble, I wish it were bigger.” ■