Why Japan will profit the most from artificial intelligence

The country’s shrinking population and aversion to mass immigration mean it is well placed to embrace robots and AI in the workforce

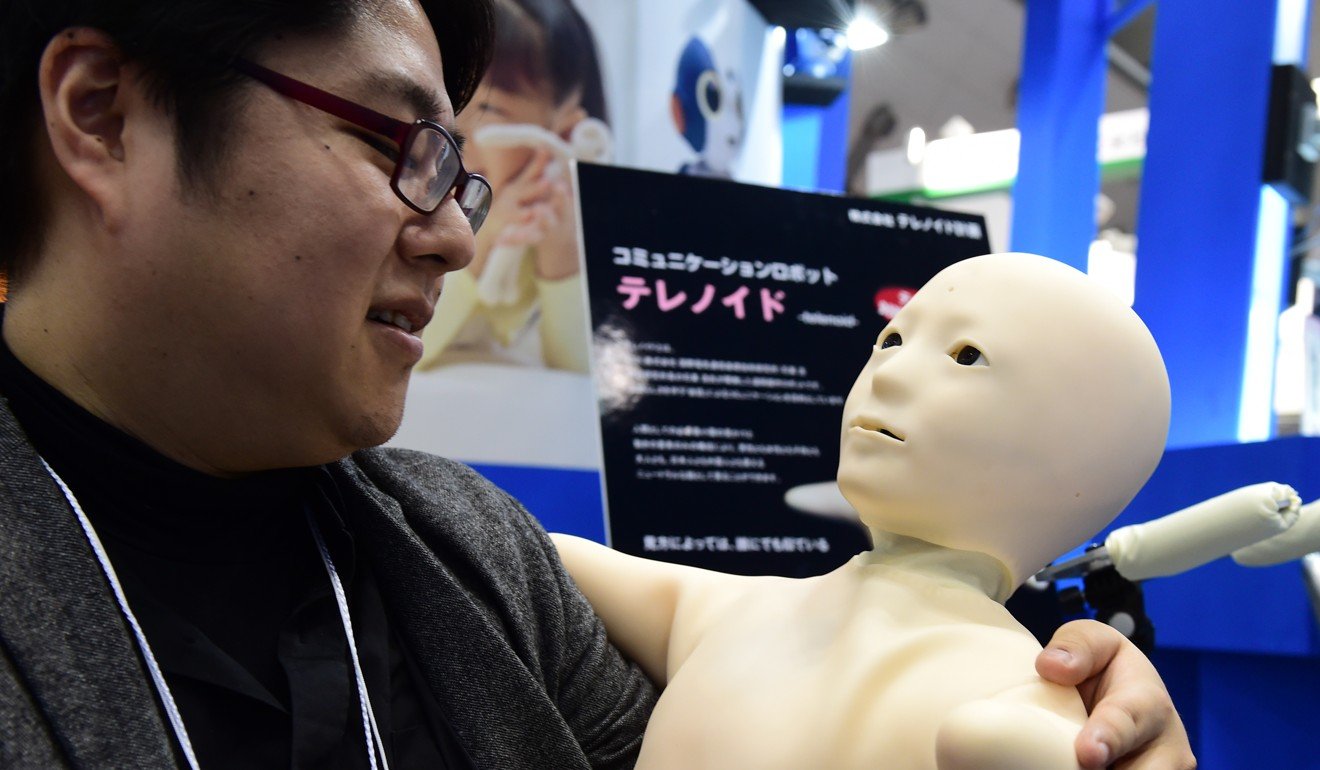

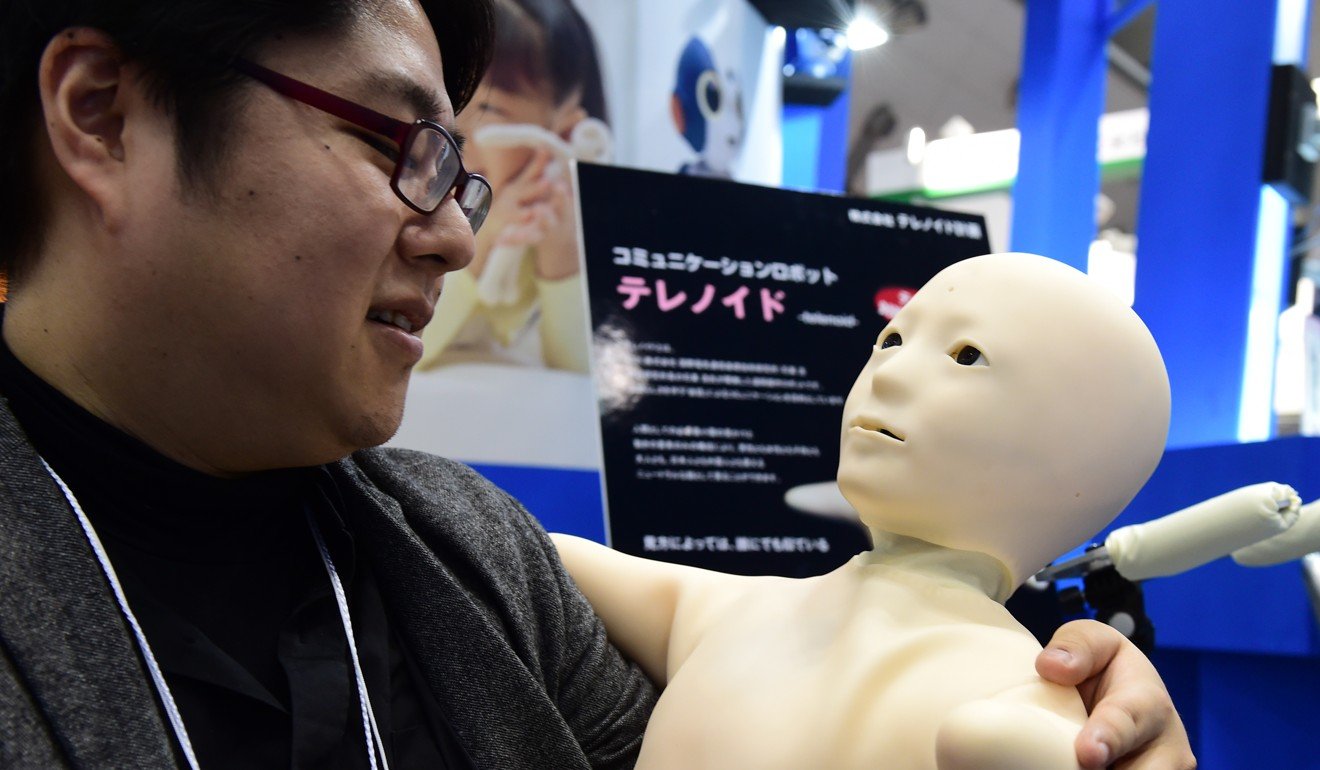

A resident of the Silver Wing Social Care elderly care home in Tokyo’s Chuo Ward chats happily to a staff member in the facility’s communal area, while in a nearby room another senior is being helped by a rehabilitation specialist to walk again after a fall last month. These workers never take a day off, never complain and don’t need to be paid, for they are robots.

Silver Wing Social Care provides a glimpse into the future of Japan and indeed other industrialised nations as they follow its path to ageing societies and labour shortages. The company’s flagship care facility began using robots to help care for residents four years ago after being selected by the city government as a test project.

Japan is entering uncharted territory for a modern economy. A consistently low birth rate has shrunk the working-age population by around 10 million since its mid-1990s peak, with another 20 million set to disappear from workplaces in the coming decades. The situation is becoming critical, with nearly 1.5 vacancies for every jobseeker and chronic shortages in sectors such as nursing care, manufacturing, construction and parcel delivery.

At a time when the government is pressuring companies to cut infamously long working hours, raise wages and ensure holidays are taken, and in a country still unwilling to countenance mass immigration, robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) look to be the only solutions.

“We tried out various kinds of robots to see which would work best for us. We’ve gradually increased their use and now have 20 different models operating, including robots for nursing care, rehabilitation, communication and recreation,” explains Silver Wing’s Yukari Sekiguchi, who oversees the programme.

The company’s staff used to regularly injure their backs lifting residents, leading to them being off work or quitting the profession altogether, a major problem given the tight labour market. Workers can now use robots they stand inside to help them do such heavy lifting.

“A lot of people thought that elderly people would be scared or uncomfortable with robots, but they are actually very interested and interact naturally with them. They really enjoy talking to them and their motivation goes up when they use the rehabilitation robots, helping them to walk again more quickly,” says Sekiguchi.

Japan may be the best-placed country to cope with the advance of automation – it’s likely to cause less unemployment than elsewhere, given the shortage of workers and lifetime employment practises. Unemployment has fallen to 2.8 per cent and a record-high 97.6 per cent of new university graduates found jobs by the start of the business year in April.

The situation should be a boon for workers, but gains are being distributed unequally. Despite the tight labour market and many companies logging record profits, wage inflation remains stubbornly sluggish.

“There is a shortage of manual workers, but an excess of white-collar workers, especially middle-aged men,” says Naohiro Yashiro, a labour economist and dean of the Global Business Department Showa Women’s University in Tokyo.

“The government has set an inflation target, but it’s not happening yet. My explanation of this mystery is there is a kind of structural reform going on. The seniority based wage system, whereby employees’ wages in Japan rise rapidly with their age is not sustainable anymore, with the ageing of the population,” says Yashiro, an adviser on labour economics to three prime ministers.

Companies are thus trying to halt automatic salary raises for workers in their 40s and 50s, and increase pay for younger ones, with one largely offsetting the other, according to Yashiro.

It is these mid-level workers who would normally be most at threat from the oncoming wave of robotics, AI and other new technologies. But in Japan, they should be saved from unemployment, if not wage stagnation, according to Dr Martin Schulz, senior economist at the Fujitsu Research Institute.

“Much of the debate about automation squeezing workers out of the labour market is not an issue in Japan. Wages at the lower end won’t be squeezed much because automation is costly, so the cheapest workers won’t be replaced. At the top end, people with skills are usually helped by digitalisation because they benefit from new systems,” says Schulz.

“The squeeze would be at the mid-level. But they are comparatively protected in Japan by labour regulations. So they are not hit as hard as they are in, for example, the UK or US, where we are seeing political disruptions as a result of this,” says Schulz, referring to the Brexit vote and election of Donald Trump.

But neither the government’s employment reforms nor automation are the solution to Japan’s labour problems, according to Toyonori Sugita, owner of Daimaru Seisakusho, a metalworking factory just outside Tokyo.

“If we put up wages and reduced hours as the government is suggesting, we’d go bankrupt. But the shortage of workers in technical industries is terrible now,” says Sugita, who is looking at bringing back skilled workers in their 70s.

“Automation isn’t the answer either. The type of work that can be automated is going overseas to other Asian countries; work that requires high levels of technical skills is what remains in Japan and can be profitable,” says Sugita.

“We need more workers from overseas, from the Philippines and places like that. If the government is going to do something, it should promote that,” adds Sugita.

But with advocating mass immigration still seen as political suicide in Japan, the march of the robots looks set to continue. ■