Indian invasion of Chinese social media apps like TikTok, SHAREit and Helo sparks fear and loathing in New Delhi

- As Chinese social media apps like TikTok take India by storm, they stand accused of everything from spreading sexually explicit material to spying and crowding out local competitors

- With government alarm bells ringing and calls for outright bans, the clock could be ticking on their time in the sun

A scantily clad girl walks in front of her boyfriend, seeking approval of her outfit. He shakes his head. She puts more items on, and then a few more, but still no luck. Finally, she puts on a burka and her boyfriend cheers: “Wow, perfect!”

The skit, mocking Indian men who expect their partners to dress conservatively, is just one of Radhika Bangia’s creations on TikTok, a Chinese-made app for creating and sharing short videos that has taken India by storm.

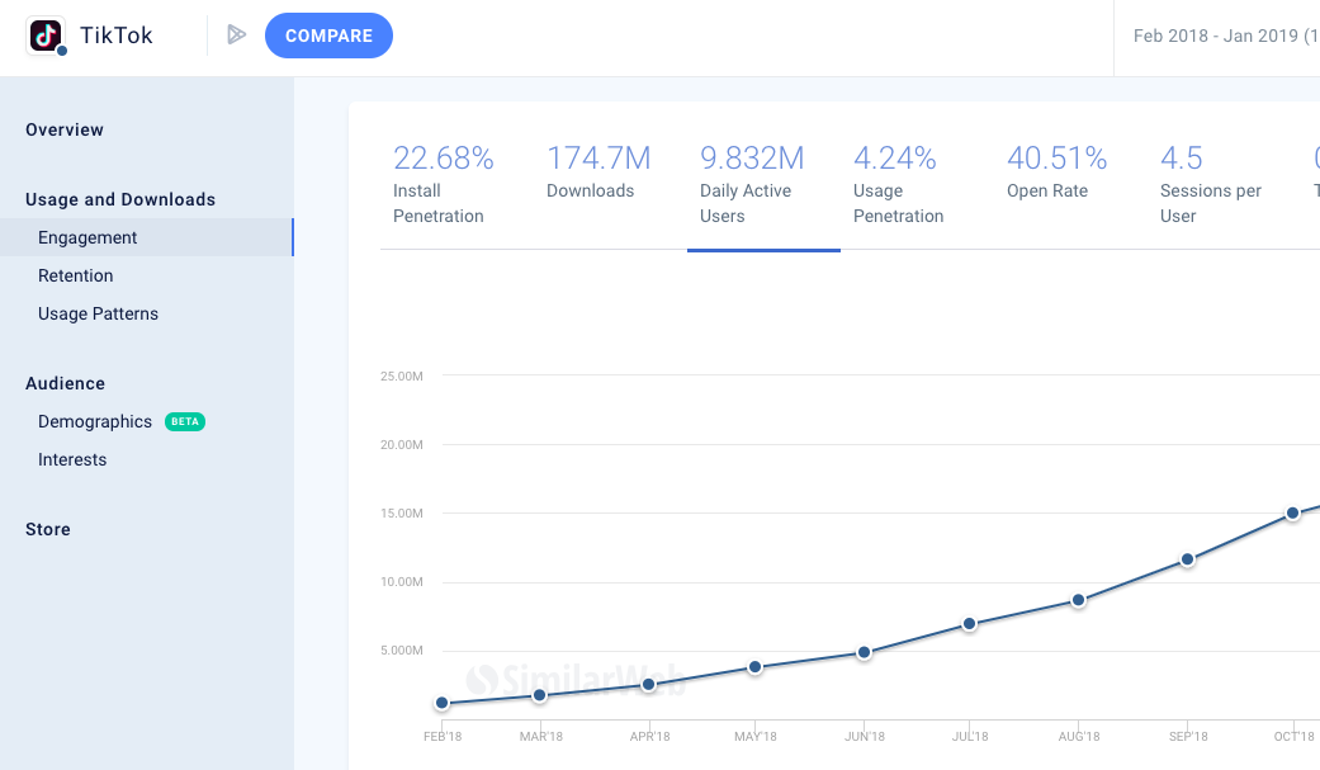

The country now accounts for about 40 per cent of the app’s 500 million users, according to the analytics firm Similar Web.

Rising stars like Bangia are among the many beneficiaries – she is one of about 50 Indians, mainly comedians and actors, who have amassed more than a million followers on TikTok. Their popularity in part reflects India’s unique demographics – 65 per cent of its 1.3 billion people are below the age of 35 and more than 400 million of them own a smartphone. But it also reflects a growing trend in which Indians are turning to Chinese-developed social media platforms.

Networking apps and e-commerce platforms such as UC Browser, SHAREit, Club Factory, Helo, Vigo and LIKE have all experienced similar explosions in popularity. Helo, a networking app made by China’s Toutiao, grew its Indian user base from around 60,000 in June 2018 to more than 6 million in January 2019, according to SimilarWeb.

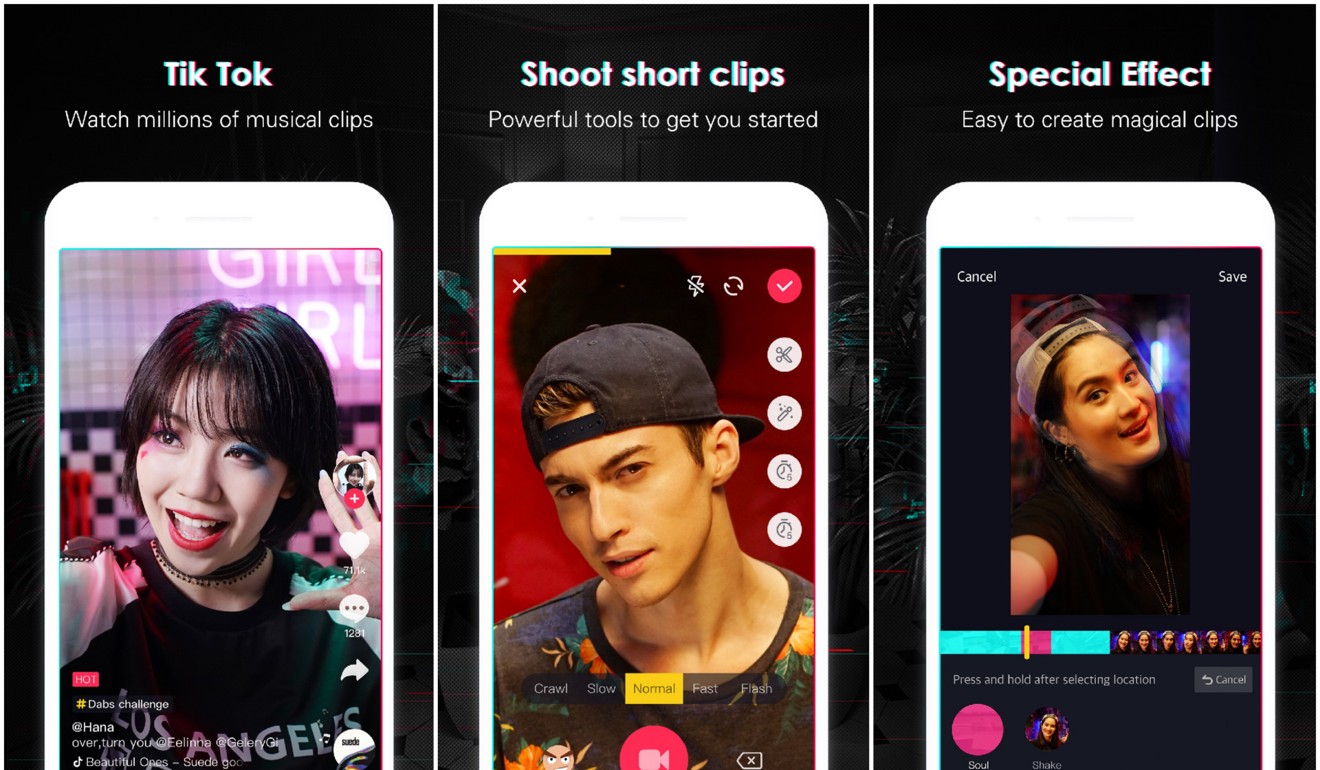

For TikTok, owned by Chinese firm Bytedance and originally known as Douyin in China, part of the appeal is its accessibility. Anyone with a basic smartphone and moderate-speed internet can use it to create and share professional looking 15-second music videos featuring themselves, something that has proved an irresistible draw in a nation obsessed with its film industry.

The app provides the special effects and the users, like Bangia, provide the talent. “There are so many interesting challenges to participate in and hundreds of filters, stickers and effects to choose from that make my videos stand out,” Bangia says.

BAD APP-LES?

Popular as such apps may be, their rise has prompted a wave of controversies. Various apps have been accused of spreading fake news, hate speech and sexually explicit material. And TikTok, which can be used by anyone above the age of 13, is among those feeling the heat.

The southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu wants the federal government to introduce an outright ban on TikTok, which it blames for the spread of “sexually exploitative” videos. In December last year, a state-backed helpline received 36 calls complaining of harassment and bullying related to the app. Police in the state have arrested men accused of using TikTok videos to advertise prostitution. Failing an outright ban, Tamil Nadu wants powers to regulate its use within the state. Local police in some areas have advised parents and schools to keep track of children who use the app.

Such problems have been exacerbated by the marketing strategies of TikTok and similar apps. Most Chinese apps target India’s Tier-2 and Tier-3 areas – semi-urban towns which aspire to compete with its cities – leaving the urban audience to more established players like WhatsApp, Twitter and Facebook. Critics say this means a disproportionate number of users are new to the internet and vulnerable to its social ills.

The apps have shown signs of responding to these controversies. TikTok, for example, recently appointed Sandhya Sharma, formerly with MasterCard, as its public policy director and says it is considering further hires to tackle the problem.

Even so, political pressure is growing.

Last month, Swadeshi Jagaran Manch (SJM), the economic wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (the ideological parent of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party), wrote to Prime Minister Narendra Modi to recommend a blanket ban on Chinese apps, citing national security.

“Data is now considered the new oil. We should not allow Chinese companies to capture Indian user data without any restrictions or monitoring,” read its letter to Modi.

Ashwani Mahajan, the co-convenor of SJM, told This Week in Asia his group opposed Chinese apps because they collected sensitive information, such as users’ location and photos, which could potentially be misused.

Asked what made these apps any different to others that collect similar information, he replied bluntly: “But it is China”.

“We’re concerned with other apps perhaps for data-mining related issues but with the Chinese ones, there is a strong security angle,” Mahajan said.

The SJM is far from alone in harbouring suspicions. In January, a report by IT security firm Arrka Consulting found six in 10 of the most popular Chinese apps in India were asking for data that was not required, such as access to cameras and microphones. The study, commissioned by The Economic Times newspaper, found the apps were transferring data to other parties, with 69 per cent of the data going to the United States.

TikTok, it said, sent data to China Telecom, while UC Browser sent data to its parent company, the Chinese mobile internet provider UCWeb (which, like the South China Morning Post, is owned by Alibaba). Vigo Video, it said, sent its data to Tencent.

DEVOURING DRAGON

The rise of Chinese apps in the Indian ecosystem has led to the sidelining of other players, domestic and global. Chinese apps accounted for 44 of the places in Google Playstore’s top 100 – up from 17 the previous year.

In the face of stiff competition from ByteDance’s Helo app, local start-ups ShareChat and Clip App have been forced to merge into a single entity. ShareChat, which also targets users from smaller towns and cities, had seven million downloads in January, compared to 10 million downloads of Helo.

The huge resources available to Chinese firms play a significant role in beating the competition.

“The Chinese apps come with a kind of stability and money-power pumped in,” says Zafar Rais, CEO of the market research firm Mindshift Interactive.

Given a nationalist party is in power in India, this story of Chinese dominance creates its own set of problems. The Modi administration positions itself as a Beijing-sceptic and this frequently reflects in its policies regarding Chinese products and services.

In December 2017, the defence ministry advised armed personnel against the use of 42 Chinese apps including SHAREit, WeChat and MiStore, classifying them as “spyware”. It told them to uninstall the platforms from their mobile phones.

The ministry of electronics and information technology has also weighed in, drafting legislation that requires the owners of apps that have more than five million users in India to set up local offices so they can be held accountable. Under the legislation, app owners would have to establish “automated tools … for proactively identifying and removing or disabling public access to unlawful information or content”.

In taking action against this new wave of apps, New Delhi is also aware of the experience of other markets across Asia. A South China Morning Post investigation in May last year found that via TikTok Hong Kong children as young as nine had exposed their identities and private information to millions of users. In Indonesia, TikTok faced a brief ban for allowing “pornography, inappropriate content and blasphemy”, while US authorities have recently fined the video-sharing network for gathering children’s data.

A senior official at the ministry told This Week in Asia the government was serious about implementing tough laws and that the “top leadership” was waiting for an appropriate moment. The official insisted a clampdown on Chinese apps was on the cards, saying it was “only a matter of timing”. ■