In Southeast Asia, a land without Uber has an Uber for everything

- The big daddy of on-demand services may have retreated from the region, but its legacy lives on

- A wave of start-ups that learned from its example now offer an ‘Uber for everything’ – from caregiving to groceries, massages to helicopter rides

Ride-hailing giant Uber may have retreated from Southeast Asia, but there can be little doubt that it has left its mark on the region’s start-ups – many of which might not be around today had they not learned from its mistakes.

When the company arrived in Singapore, in 2013, its now-familiar online app connecting customers and drivers and its clear pricing system were a revelation in a region where customers had previously relied on word of mouth and Google searches.

Its business model helped give birth to competitors such as Indonesia’s Go-jek and Singapore-based Grab, which went on to acquire the San Francisco-based company’s loss-making Southeast Asia operation in March last year.

But it also inspired something far beyond its immediate competitors: a new sector offering an “Uber for everything”, as start-ups raced to become the first to launch on-demand services in areas as diverse as grocery delivery and laundry services to helicopter hires and senior care.

Examples of its lingering influence include Honestbee, a Singapore-based on-demand delivery service for food and groceries that has expanded to eight cities including Jakarta, Bangkok, Manila and Hong Kong; the marketplaces Kaodim in Malaysia and Seekmi in Indonesia, which offer services from professional cleaners to photographers; Helpster, which connects blue-collar workers with employers in Thailand and Indonesia; and Singapore’s Homage, connecting carers with the elderly and disabled.

Few, however, have the reach of the on-demand behemoths Grab and Go-jek, which have widened their offerings in recent years to include everything from massages and beautician appointments to package deliveries and on-call mechanics.

“Uber [helped] companies such as Grab and Go-jek to learn best practices by competing with it,” said Arnaud Bonzom, co-founder of the Singapore-based Map of the Money, which tracks Southeast Asia’s start-up companies.

“The on-demand firm [had] an unprecedented speed of execution to scale and provided amazing customer service.”

“A new wave of founders and angel investors of app-based on-demand services are former employees of Uber,” Bonzom added.

Tiger Fang, who helped launch Uber’s operations in Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia, is one of them. He co-founded the Jakarta-based Kargo, of which he is also CEO – a kind of Uber for trucking and logistics.

“I was very lucky to have started Uber’s business in Indonesia and we had a great team. When Uber left, the team was sort of left with wondering how can we as a team work together, that’s the opportunity. We wanted to try to solve a problem together,” he said.

“[Indonesia] spends so much money on logistics but truck drivers are barely making a living, so we want to help some of them out.

“What we want to do is utilise technology to connect existing transport providers to shippers in a more efficient manner. Right now a lot of trucks are dedicated to just serving one customer. We want to make [them] basically service many customers.”

The 32-year-old, who was born in Hangzhou and grew up in Hawaii, sees massive potential for growth in Indonesia’s logistics industry. Logistics costs in the archipelago nation equal about 25 per cent of GDP – almost US$250 billion – mainly because of the inefficient utilisation of assets, according to Fang. He said more developed countries such as the US, Singapore, Germany and Japan, spend less than 10 per cent of GDP on logistics.

Kargo’s platform is designed to drive down costs while also helping truck drivers, who currently make about three to 5 million rupiah (US$211-US$351) per month, according to Fang.

“With [our] technology we can send the truck that’s best fitted for you, [at] the right time, [to] the right place, at the right price,” Fang said. “If you can do that at scale, then we can bring down the cost of inefficiency.”

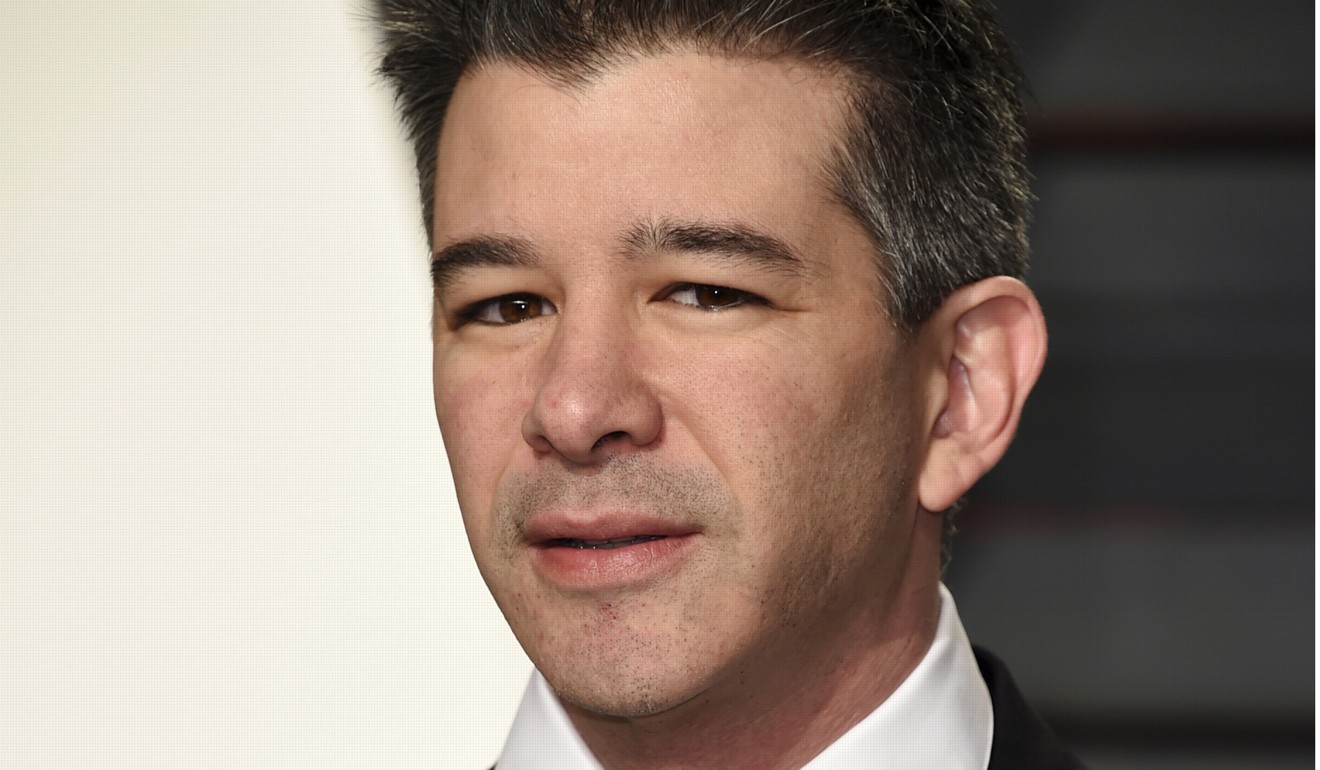

The company recently raised US$7.6 million in seed investment from venture capital firms Sequoia and 10100, the later of which is run by Uber’s co-founder and former CEO Travis Kalanick. The money will be used to fine-tune Kargo’s app, which is still undergoing testing, but is envisaged as a platform to connect companies, individual business owners and small and medium-sized enterprises to truck operators and third-party logistics service providers.

For now, the company’s clientele comprises companies selling fast-moving consumables, as well as manufacturers and retailers. Its services are focused on the islands of Java and Sumatra, which Fang says contribute most of Indonesia’s economic output.

“We find that Java and Sumatra account for a huge percentage of the population and an even bigger share of Indonesia’s GDP,” he said. “These are two big islands connected by a short ferry ride, that’s why trucking is so important here.”

Deliveree, a regional competitor, operates in Thailand and the Philippines as well as Indonesia. Like Kargo, it offers various types of vehicles to suit users’ needs.

Other former Uber employees to make their mark on Southeast Asia’s start-up ecosystem include Alan Jiang, the company’s country manager for Indonesia who was then Asia chief for Chinese bike-sharing giant Ofo before becoming chief executive of Beam, an electric scooter-sharing company based in Singapore.

“Ride-hailing is a very competitive sector, it’s a high-frequency business but the margins are low,” said Willson Cuaca, managing partner at East Ventures, a Southeast Asia-focused investment fund. “Even ride-hailing apps have moved beyond ride-hailing for revenue, such as Go-jek and Grab which now aim to be a super-app. The challenge now lies beyond on-demand transport.”

The two companies enjoy something of a regional duopoly when it comes to land transport, which is why Lionel Sinai-Sinelnikoff has his eyes on the skies.

The 40-year-old entrepreneur from France founded Ascent, an on-demand helicopter start-up, in May last year. It currently has a fleet of five helicopters operating in Manila and Clark in the Philippines, with plans to expand to Thailand, mainland China and Hong Kong.

“The similarity [with Uber] is that we ‘Uberised’ the supply. We are tapping unutilised assets owned by professional helicopter operators,” he said.

“We are basically a booking engine, what we’re doing is on-schedule and on-demand trips, where we fly you at your [desired] time.”

Sinai-Sinelnikoff, who is also the start-up’s CEO, had the idea for the service after seeing how quickly ride-sharing had taken off. “Air mobility with helicopters has been around for half a century, but not democratised, due to high prices and complex processes,” he said. “Since then, the digital economy as well as ride-sharing and on-demand business models came along. It is then natural to mix both to bring to life an urban air mobility concept, where you can book your seat on a helicopter flight instantly.”

Uber’s business model may be easy to emulate, but the high levels of upfront capital required can make it expensive to compete.

The ride-hailing giant fell foul of this itself after trying, and failing, to undercut Didi Chuxing in China, and Grab and Go-jek in Southeast Asia on price. The ensuing discount wars saw it incur such heavy losses that it eventually withdrew from both markets.

Even after its Southeast Asian business was acquired by Grab, Uber posted a loss of US$1.8 billion on US$11.3 billion in revenue last year – though this was an improvement on a loss of US$2.2 billion the year before.

The company’s main US rival, Lyft, likewise posted a loss of US$911 million on revenue of US$2.16 billion in 2018, while in China, food delivery giant Meituan Dianping reported an adjusted loss of 8.52 billion yuan (US$1.27 billion) for the year. Clearly, profits in the industry are hard to come by.

But back in Jakarta, Fang is optimistic that his new venture will not meet the same fate as his previous employer.

“What I learned from Uber is the hustle, that we’ve got to move fast, think fast, and ship fast. We have got to be very careful and have a very high standard for the people that we hire,” he said.

“I also learned not to spend too much money. I don’t want to burn money like crazy.” ■