US, Chinese unicorns may lead, but South Korea shows it’s not a two-horse race

- South Korean banks remain reluctant to invest in start-ups, an aversion to risk that is a legacy of the 1997 financial crisis

- The government has pledged to invest US$5.9 billion in the field by 2022, but there is a long way to go – especially as the huge chaebol are still favoured

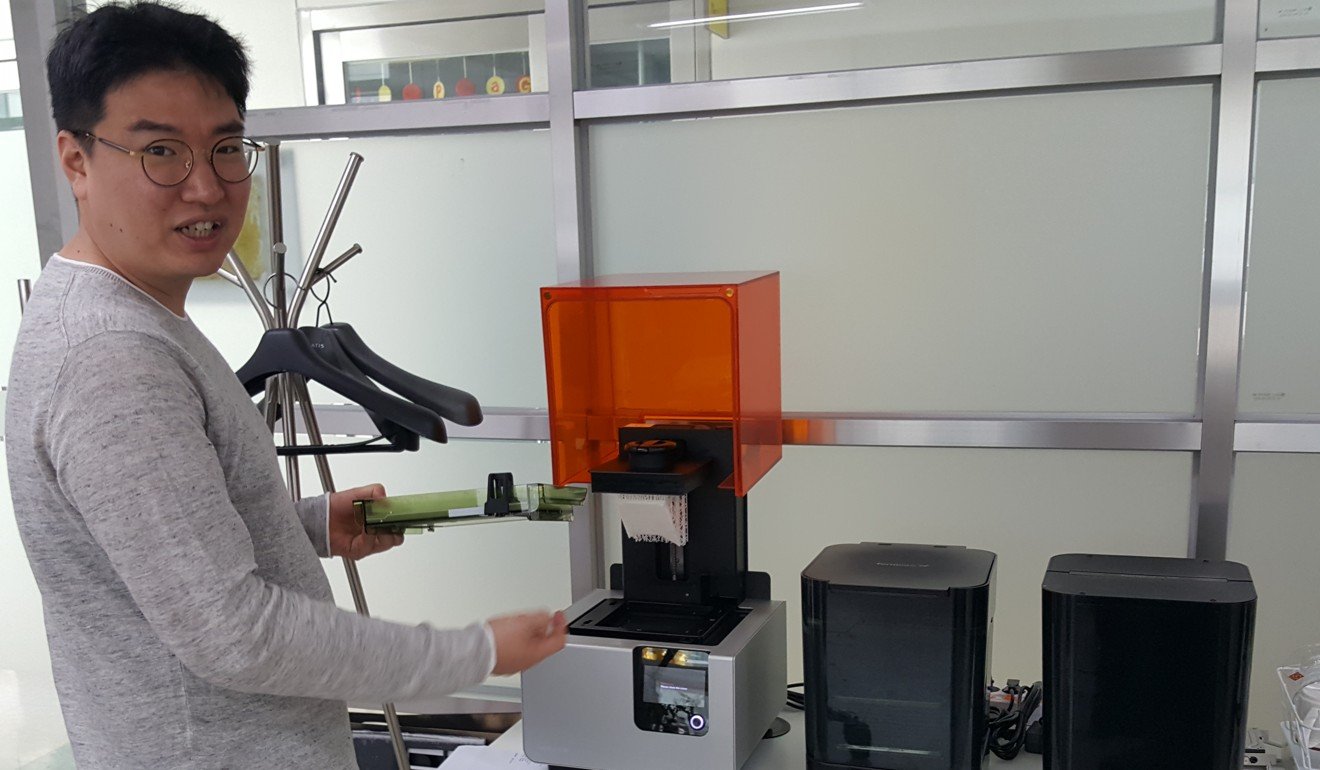

Park Jae-hyun is the 33-year-old chief executive of The Ant Institute, which fosters creative hobbies for people interested in arts and crafts. “Easy-to-do art education” being its motto, the start-up creates instructional videos such as making paper animals and painting watercolours of flowers.

With a target audience of adults and children alike, the company’s YouTube channel has so far logged 4,000 viewing hours and amassed 1,000 subscribers, allowing it to monetise its videos. However, The Ant Institute also makes commercial advertisements for private clients on the side to keep the business afloat.

Park’s company has just reached its three-year anniversary, a milestone for many start-ups, and even more noteworthy in South Korea, where business has long been dominated by vast, family-run conglomerates known as chaebol, such as Samsung, LG and Hyundai.

“Not many start-ups make it through the ‘death valley’, or the first three years, because of the small window of opportunity for Korean start-ups,” he says. “Our country doesn’t have a big capital market like the United States or the European Union, where start-ups with solid ideas attract investments from all around.”

But there has been a significant shift in the South Korean government’s attitude towards start-ups. The country’s Financial Services Commission recently pledged 7 trillion Korean won (US$5.9 billion) for start-up investments by 2022. This follows an investment of 8 trillion won allocated between 2018 and 2020 from a pooled investment fund run by the Korea Development Bank, a state-run policy lender, and K-Growth, an independent fund management company.

According to the Korea International Trade Association, South Korea’s annual investments into start-ups grew 106 per cent last year to US$4.5 billion, while the US and China grew 21 per cent and 94 per cent respectively.

This transformation has been driven in part by the success of South Korean “unicorns” – the term given to a start-up valued at US$1 billion or more. Such Korean companies include e-commerce website Coupang, valued at US$9 billion, and the video game developer Bluehole, valued at US$5 billion, according to tech trend forecaster CB Insights.

But the country still has a long way to go. Despite lagging in terms of growth, start-ups in the US and China attracted investments that dwarfed their South Korean counterparts last year, receiving US$99 billion and US$113 billion respectively.

“Diversity is still lacking in South Korea,” Park says, alluding to the outsize respect given to major corporations in the country. “Someone who comes from nothing like Steve Jobs is ostracised.”

But that, too, may be changing. Park is a recent graduate of the Youth Start-up Academy – a one-year programme operated by the Ministry of SMEs and Start-ups.

Last year there were about 1,000 entrepreneurs enrolled in the academy, which has an annual budget of 100 billion won (US$83 million). Students attend classes and receive 70 per cent of costs, up to 100 million won, to start the operations of their companies.

Since 2011, 2,871 students have graduated from the academy, and alumni companies have recorded profits totalling 1.8 trillion won while hiring 5,600 employees.

Chung Da-jung, 29, is one of Park’s classmates from the academy. She was working at an air compressor company before founding Fluidcomp, a start-up that imports energy-efficient and reasonably priced air compressors. The company has sold more than 100 compressors since launching in 2017.

“Many of our domestic customers lean towards buying products from well-known brands,” Chung says. “I’m quite glad that energy-efficiency stickers will start appearing for air compressors later this year, as this can prove that our products are just as good, or even better, than products from big companies.”

Nevertheless, South Korean banks remain reluctant to invest in start-ups, an aversion to risk that is a legacy of the 1997 financial crisis, which resulted in the International Monetary Fund providing the country with a US$58.4 billion bailout package.

Domestic investors are also much more likely to choose a major company over a start-up even if the latter has better products or ideas. When it comes to venture capital funds, investors prioritise finance experience or personal background over entrepreneurial or operational experience.

“The proportion of our finance for venture investments is not big, as 90 per cent of our operations are giving out loans,” says Cho Young-hoon, who works in development for the government-run Korea Development Bank, adding that most Korean banks took similar views of the risk factors involved in investing in start-ups.

A former venture capital investor, who declined to be named, said unlike their American counterparts, Korean banks did not assess the potential marketability of companies. “It’s because these banks are satisfied with surviving just on profit from interest,” he says.

The investor said real estate seemed to be the most secure investment in the country. “When you’re talking about banks making investments, it’s with land – that makes the most profit for them.”

The government has a long history of concentrating development and trade on a few chaebol, while there is also a one-sided relationship between start-ups and major corporations in the country. Market items advanced by start-ups, such as ride-sharing or cordless vacuum cleaners, are quickly noticed by these larger companies.

“While US institutions focus on individual abilities when assessing the marketability of a start-up, this style of luring investments does not work in a country where groupism is strong,” Park says.

“Because start-ups with a good item in the market have no choice but to accept big investments from major corporations, bigger companies take what they need from start-ups and are able to sell the shares altogether if they purchase enough stock.”

Becoming a civil servant – such as a police officer or a town hall employee – is one of the most coveted jobs in South Korea. More than the honour of serving the country, becoming a civil servant ensures a steady payroll, pension and social recognition. In this sense, start-ups – with their built-in risk and uncertain future – are the complete opposites.

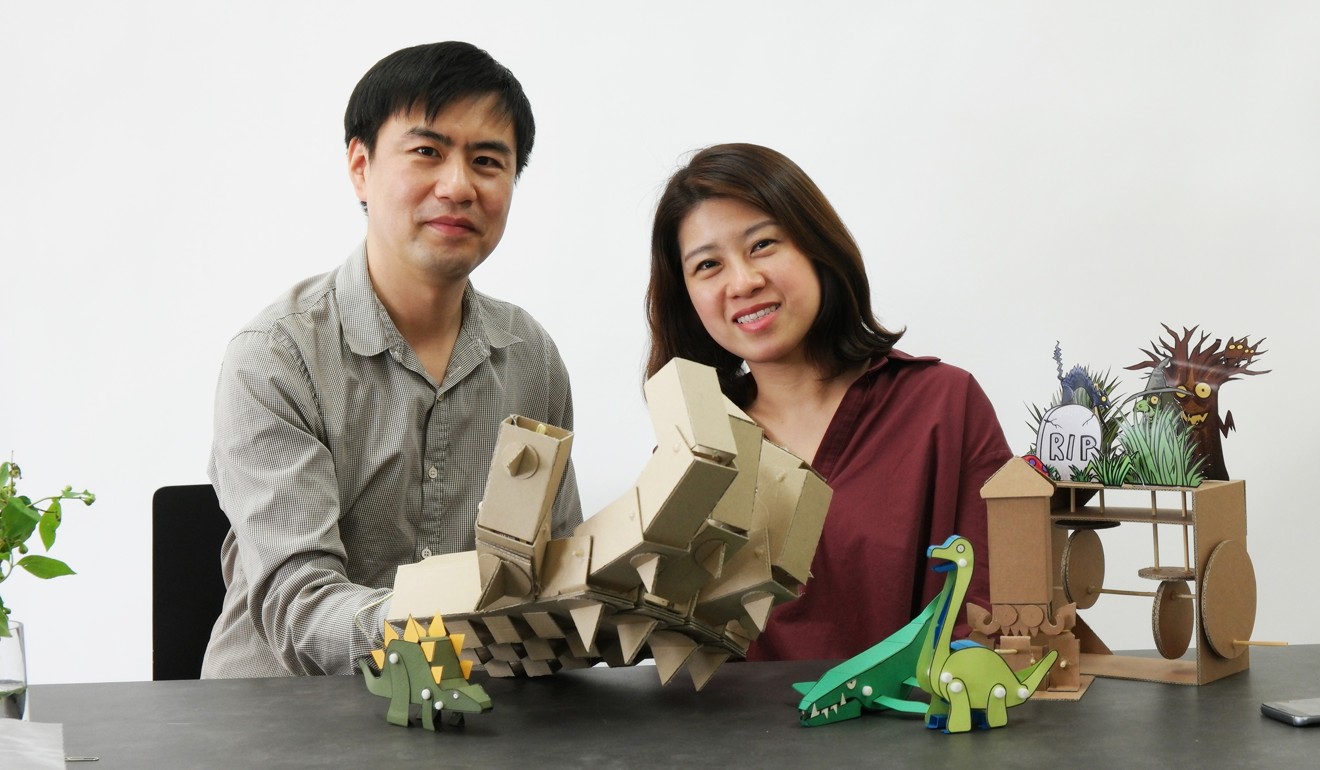

There are currently three workers at The Ant Institute, with CEO Park working alongside married couple Hong Yoo-kyung and Lee Dong-kuk, both of whom are 40.

In the past, the couple had strenuous but coveted jobs. Hong was an experienced art instructor at a major test prep institution, and Lee worked at Nexon, the country’s most well-known video game company.

“Our family and friends’ reactions to our decision are still not good,” Hong says. “Since we have kids and we are not a young couple, people are concerned about our futures.”

Park, however, allows the couple to leave early enough to pick up their kids from school. To Hong, being able to take weekend trips and having more family time was a big reason for the couple to change jobs.

Even if the success of the company is still too early to assess, the couple thinks of their transition as an investment in their careers. “My current work here has an adventurous side that I was missing, and I feel like my career has more potential in this company,” Lee says.

Though they took a pay cut to work at The Ant Institute, Hong and Lee are also shareholders of the company. Park recruited the couple as they were close acquaintances he could trust; their children call Park their “uncle”.

Hong saw that her husband felt trapped inside his previous workplace. “His gaming company was dictated by the idea of making more profit rather than coming up with new ideas,” she says.

Their relationships with colleagues have also seen a major but positive change.

“There was this ‘just do enough to get through’ mentality among my colleagues when I worked for my gaming company, which hired thousands,” Lee says.

“But in our office, we need to personally feel affection for each other in order for this small company to grow,” Hong adds.

On The Ant Institute’s third anniversary in March, the three colleagues celebrated their first year of positive net revenues.

“I know that not one of the three of us in this office is considered ‘normal’ by the Korean standard,” Hong says. “We don’t care too much about what others say about us; we just do what we feel is right for us.” ■