As Myanmar embraces China, can it reap the rewards?

- Myanmar pulled the plug on its controversial Beijing-backed Myitsone dam project in 2011 but has since opened the floodgates to cooperation on other large-scale infrastructure

- Now a major part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the task for officials is to win over a sceptical public, and make sure the benefits trickle down to all

Myanmar’s decision-makers have interacted with Chinese partners on infrastructure and investment projects in a seemingly dichotomous manner in recent years. But in a sense, their decisions reflect a practical logic that takes into account the concerns of both the communities affected and the population at large. The abrupt suspension in 2011 of a billion-dollar hydropower dam project at Myitsone in Kachin State, and more recent agreements entered into by the current government to bring Myanmar closer into the orbit of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, present contrasting examples of Myanmar’s approach to Chinese projects. They also illustrate the practical logic that characterises that approach.

Myanmar hit the pause button in its infrastructure deals with China in September 2011, when the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) government led by former president Thein Sein suspended the Myitsone dam project for the duration of his administration. That administration ended in March 2016, and the question of whether construction should be resumed, and of whether something else could be done with the project, has become a heated and emotional issue.

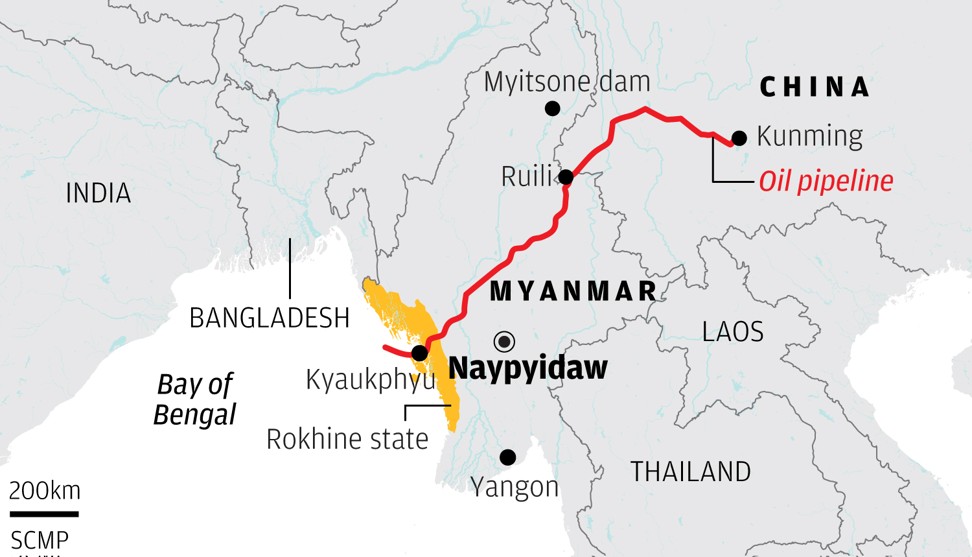

In today’s Myanmar, the democratically elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government now seems to have moved to the fast-forward option in its economic interactions with China. A memorandum of understanding for the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) was signed in September 2018. A related agreement to develop a deep-sea port at Kyaukphyu in southern Rakhine State, together with a special economic zone (SEZ), was signed in November 2018. The 1,700km corridor would connect Kunming, the capital of China’s Yunnan province, to Myanmar’s major economic centres – Mandalay and then Yangon – and to the Kyaukphyu SEZ. It would link the least and most developed areas of the country.

The CMEC project raises a series of issues that some view as a greater threat than the Myitsone dam. While the Myanmar government is not noted for taking bold moves or making firm decisions on complex issues, the CMEC may represent an exception, not least because it is linked to the Belt and Road Initiative. How then should the country go forward as a relative newcomer to the belt and road experience, with the lessons available from other parts of the region and the globe?

FLOOD OF CONTROVERSY

Strong views concerning the stalled Myitsone dam project expressed on the Chinese side have revived and heightened the controversy. The opinions of former ambassador to Myanmar Hong Liang, who headed the Chinese embassy in Yangon, were posted on the embassy’s Facebook page. This was in addition to views highlighted in a People’s Daily editorial. These statements revealed China’s perception that the project is an important part of the belt and road programme and that any further delay in its construction could hamper bilateral relations, including investor confidence, and affect Myanmar’s credibility. The NLD government has resorted to the long tradition in Myanmar of problem-solving by committee. A 20-member commission to review the Myitsone dam, including its environmental and social impacts, has produced two reports. These have yet to be released publicly, leading to speculation that they probably found the project had more disadvantages than advantages.

Concerns and misgivings among the Myanmar people over the Myitsone project were further stoked when Hong visited Myitkyina, the capital of Kachin State, in late December 2018. Upon meeting with Kachin political and religious leaders, the ambassador claimed that some Kachin leaders supported the project. This caused dismay and disbelief and a storm of protests, demonstrations, and intense and widespread calls for the termination of the dam.

Several technical and environmental assessments, including a 2018 report on Myanmar’s hydropower sector, offer evidence of the case not to resume construction. The Myitsone issue has also rallied people of different ethnic nationalities and faiths around a consensus against resumption. Even a cabinet member has weighed in with his views.

Several remarks made by Thaung Tun, the union minister for investment and foreign economic relations, indicate a growing realisation that Myanmar should consider Malaysia’s example of maintaining good bilateral relations with China by negotiating new projects, while sending a clear signal that projects concluded with a previous regime may not be in the best interests of all concerned.

Doing “something else in place of the Myitsone dam”, as the minister suggests, may mean embarking on the CMEC and Kyaukphyu SEZ projects in close cooperation with China.

Patience, hard work and a more inclusive approach to economic development on Myanmar’s part will set the country speeding along on China’s proposed New Silk Road. What will this entail for Myanmar? Information and implementation go hand in hand.

Myanmar society is largely not aware of the Belt and Road Initiative, and knowledge of the scheme is limited to government officials and elites engaged in policy research or dealing with China. The information gap is not so much about the lack of access to information, which is readily available on the internet, but more about the extent of awareness of Myanmar’s involvement in belt and road projects. Details of projects and agreements are usually not released publicly, or widely shared in discussions within the policy and research communities. While national newspapers cover visits of senior Chinese officials who engage in talks with Myanmar counterparts, details of what is discussed are usually not reported. There have also been complaints that decisions regarding the belt and road scheme are conducted “upstairs”, while mid- to lower-level officers are kept in the dark. Obviously, this must change. Not only officials further down the line but also experts, specialists, researchers, civil society organisations and the public need to be informed and consulted where their input is necessary, or in areas where they will benefit or be affected.

NEED FOR SPEED

Myanmar can accelerate the CMEC plan for mutual benefit as part of its belt and road engagement in the coming years. It should start with an official announcement that the Myitsone dam project will be replaced by the CMEC plan. The government can also leverage China’s preference for the CMEC plan to obtain funds necessary to upgrade infrastructure, such that the CMEC becomes a key component in Myanmar’s belt and road engagement. Regarding environmental, social, economic and corruption risks, lessons and advice from other countries’ experiences should be taken into account in Myanmar’s negotiations with Beijing. In addition, more transparency is clearly required to restore trust and confidence in project implementation.

As work for the CMEC project passes through many of Myanmar’s ethnic minority areas, laws will be needed to ensure the rights of minorities are not adversely affected. Such a law already exists in the form of the 2015 Protection of the Rights of National Races Law. Its stipulations have not been implemented, but they should be.

Myanmar needs to negotiate and set up a fairer trade arrangement with China, as many Myanmar businesses and industrial establishments stand to lose out from an influx of competitively priced trade and goods from their neighbour. Since Myanmar still has “least developed country” status at the World Trade Organisation, it may be feasible to approach the WTO’s Subcommittee on Least Developed Countries to help Myanmar address this problem.

It is also important to measure the costs and benefits of the CMEC project, as well as to clearly identify who benefits and who bears the costs. The decline in government-media relations over the past few years may hinder the growth of a responsible and investigative media that provides the public with useful analyses and information on a big and complex project such as the CMEC. Journalists should be given the freedom and scope necessary to provide balanced and objective ideas and information.

Myanmar must guard against the possibility of becoming overly dependent on, and dominated by, China. It must take account of the moral and material support from its partners in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, and from other key regional players, as well as from the United Nations and Myanmar’s traditional bilateral and multilateral development partners on the world stage.

Trade along the ancient Silk Road was a venture over thousands of kilometres of uncertain terrain inhabited by isolated tribes and ethnic communities. It was a remarkable achievement. The ancient businesspeople were able to pull it off thanks to their entrepreneurial spirit of entering into new ventures and territories, a willingness to take risks, and, more importantly, the ability to establish good personal contacts and relationships with native dwellers they encountered along the way. They did so mostly by both learning from and sharing knowledge, skills, ideas and experiences. This spirit of sharing and cooperation to solve common problems, and joint efforts to improve roads and passageways, inspired the launch of the New Silk Road. There is however a significant difference between the old and new. The old Silk Road was private-sector driven while the New Silk Road is mainly government or public-sector driven.

The challenges and opportunities in travelling on the New Silk Road – after thousands of years – are obviously different. There is a clear need at this time for government facilitation and support for the private sector, and for the good of the general public, through good governance. This will provide the enabling environment for private-sector-led growth. Chinese and Myanmar authorities must cooperate to steer progress. Their efforts will enable Myanmar to proceed from the present pause to a fast-forward status under the belt and road framework in the coming decade and beyond.

U Myint is the director of Tun Commercial Bank and an economic adviser to the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry. He was formerly chief of the economic division at Myanmar’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a senior economist at the United Nations, as well as chief economic adviser to former president Thein Sein. This is an edited excerpt of an article titled “Thinking, Fast and Slow on the Belt and Road: Myanmar’s Experience with China”, published in ISEAS Perspective No 90 by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore