What does Russia’s threat to torpedo Iran nuclear deal mean for oil prices and Asian economies?

- Iranian oil can return to global markets under a revived nuclear pact, easing the supply crunch brought on by the Russia-Ukraine war

- But Moscow’s demands could disrupt the nuclear talks, bring more pain to economies already reeling from high prices

Russia has threatened to torpedo an imminent agreement to revive the Iran nuclear deal by linking it to Western sanctions imposed after the invasion of Ukraine.

Speaking in Moscow late on Friday, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said Moscow had asked Washington to guarantee that Russia’s future trade with Iran would not be subjected to Ukraine-related sanctions.

Otherwise, the Kremlin would not endorse the prospective Iran nuclear deal, he said, raising the spectre of a Russian veto if and when an agreement is presented to the United Nations Security Council for approval.

Lavrov’s bombshell means a likely delay in the full-fledged resumption of Iranian oil exports. Oil analysts are hoping increased Iranian oil flows will reduce pressure on Asian and Mediterranean markets reluctant to buy Russia’s benchmark Ural blend because of growing sanctions on Moscow.

What does the nuclear deal have to do with oil?

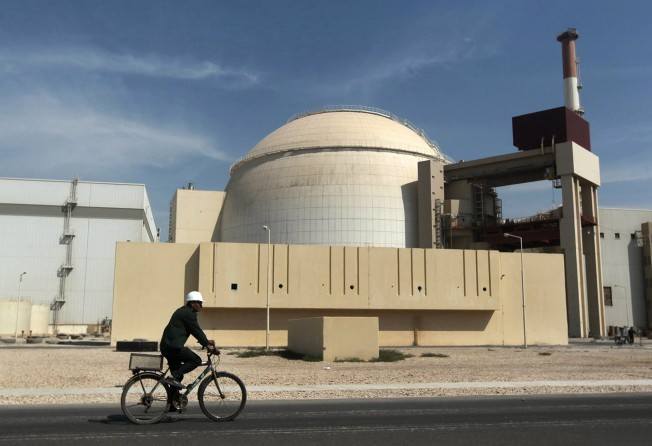

In 2015, Iran and six world powers agreed on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). They reached an agreement where most economic sanctions against Tehran, including on oil exports, would be lifted if the United Nations nuclear watchdog could verify that it was no longer enriching uranium to weapons grade levels as part of its nuclear programme.

Oil and oil product exports have been a mainstay of Iran’s economy but the United States under Donald Trump’s presidency quit the JCPOA and Washington then imposed “maximum pressure” sanctions on Iran.

Still, Iran was able to keep some of these exports flowing, with most shipments reportedly going to China through intermediaries disguising the origin of the oil shipments. But these remained below the 2.5 million barrels per day it was shipping before the sanctions. Besides mainland China, its main customers included India, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan.

For the US and its European allies, Russian oil replaced Iran’s sour crude exports. Now that they are considering banning imports of Russian oil amid its war with Ukraine and with concerns about the supply crunch, oil prices have soared to their highest since 2008. Russia exports around 7 million barrels per day of oil and refined products, or 7 per cent of global supply. It is the world’s third-largest oil producer.

“Iran was the only real bearish factor hanging over the market but if now the Iranian deal gets delayed, we could get to tank bottoms a lot quicker especially if Russian barrels remain off the market for long,” said Amrita Sen, co-founder of think tank Energy Aspects.

Yet even with the nuclear deal, there would be a staggered process of matching steps over several months before sanctions against Iran would be lifted. Tehran also needs time to achieve full production capacity, analysts said.

Analysts from JP Morgan said this week oil could soar to US$185 per barrel this year, triple the price of about US$60 a barrel just before the pandemic started.

Oil prices have been rising over the past two years amid the Covid-19 crisis, which was caused by uneven surges in demand and shortages in supply and delivery due to freight and transport disruptions.

What is the status of the nuclear deal?

Last week, before Lavrov’s comments, officials from the US, Russia, Britain and Iran said they were tantalisingly close to reaching a deal to revive the 2015 JCPOA. China, France and Germany are also signatories.

After Lavrov’s comments, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said during a television interview that the Ukraine-related sanctions on Russia “have nothing to do with the Iran nuclear deal … so I think that’s irrelevant.”

The Farsi-language daily newspaper Kayhan – widely considered a mouthpiece for Iran’s ruling hardline theocracy – described Lavrov’s threat as a “mortar attack” on prospects for the lifting of sanctions. But Ali Shamkhani, the secretary general of Iran’s national security council, on Monday downplayed Russia’s demands.

The “positive and negative actions” of countries participating in the Vienna talks are “understandable” because they are all seeking to promote their interests, he said. Shamkhani said Tehran is evaluating Russia’s demands and other “new components” affecting the Vienna talks.

After US President Joe Biden took office early last year, direct and indirect talks began in April on the possibility of the US rejoining the JCPOA.

Still, Iran continues to draw ever close to acquiring enough fissile material to manufacture a nuclear warhead, say analysts. Tehran denies it has any such plans.

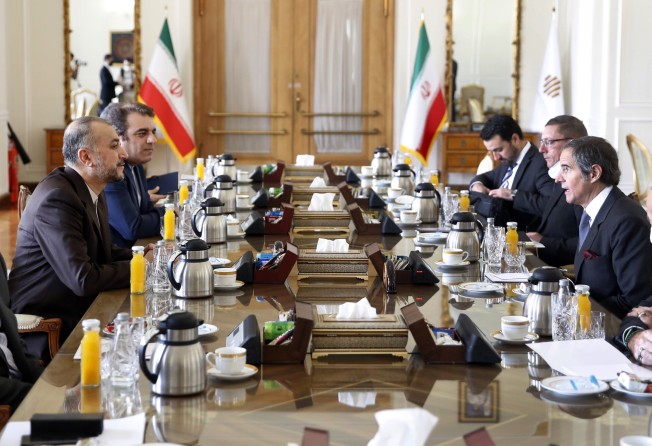

With this red line looming, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on Saturday reached an agreement with the chief of Iran’s nuclear power programme to resolve one of the four final points of dispute with the global powers.

Eurasia Group said fresh Russian demands could disrupt nuclear talks although it still kept the odds of a deal at 70 per cent.

“Russia may intend to use Iran as a route to bypass Western sanctions. A written guarantee allowing Russia to do so is probably well beyond the realm of what Washington can offer in the midst of a full-scale war in Ukraine,” said Eurasia’s Henry Rome.

What’s the impact of the rise in oil prices?

The rise in oil prices is felt by the world over. As oil prices rise, everyday costs such as transport expenses and petrol for cars will rise directly, hitting consumers’ pockets. Without a corresponding increase in wages, the purchasing power of consumers will fall.

For Asian and global consumers and businesses, the high cost of fuel will exacerbate rising consumer price inflation that has been a problem since the pandemic started.

Singapore’s Trade Minister Gan Kim Yong for example warned of rising costs of petrol and diesel for the island nation last week.

Can other Middle Eastern countries boost oil supplies?

Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Arab members of the OPEC+ oil cartel have fended off Western pressure to increase output to calm markets, because they regulate their production under the OPEC+ partnership with Russia.

When Moscow temporarily pulled out of the arrangement two years ago, the price of oil slumped to under US$10 per barrel.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have about 2.5 million barrels per day of spare capacity which they can bring to market quickly if they choose to do so.

Many Middle Eastern nations have been reluctant to take sides against Russia and have instead chosen to try to mediate an end to the war in Ukraine. They include Israel and Turkey.

Turkey shares a maritime border in the Black Sea with Ukraine and Russia. It also imports most of the gas and wheat which it consumes from Russia. Ankara and Moscow worked together by deploying forces in Syria to support rival Factions fighting the civil war.

Turkey has backed Sunni Muslim Islamist militias in Syria to counter Shia militias armed by Iran – a strategic rival of Ankara’s. It is equally concerned about Western support for Syria’s Kurdish rebels whose Turkish Kurd brethren have been at war with Ankara for decades.

Moscow has been allies with Damascus since the Cold War and Russia’s only naval base in the Middle East is located in Syria. From there, Russia has sought to spread its influence in the region, deploying mercenaries of the Wagner Group – including Syrian fighters – to fight in Libya’s civil war against the Turkey-backed government in Tripoli.

Russia’s military presence in Syria has given it leverage over Israel, which needs its tacit approval to conduct air strikes against Iranian-backed militias in Syria.

Israel’s Prime Minister Naftali Bennett flew to Moscow on Saturday for three hours of talks with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

He also spoke three times in 24 hours with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, and later discussed his conversations with German Chancellor Olaf Schultz over dinner in Berlin on Saturday.

Bennett told reporters in Jerusalem on Sunday that he could “not expand further” on his talks, but said Israel would press on with its diplomatic efforts “as needed”.

Israel said it is coordinating its diplomatic efforts with Turkey, whose deputy foreign minister Sedat Onal received US Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman in Ankara on Saturday.

The two officials agreed to coordinate US and Turkish diplomatic actions over the Ukraine war.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan phoned Putin on Sunday, a week after Ankara banned Russian warships from transiting the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits that connect the Mediterranean to the Black Sea.

Erdogan urged Putin to declare an immediate ceasefire in Ukraine, saying it would “alleviate humanitarian concerns” and could also “pave the way for a political solution,” Turkey’s official Anadolu Agency reported.

Additional reporting by Su-Lin Tan