China’s economic growth target: at maximum, the political minimum

Policymakers are faced with few options – none good – when it comes to prioritising bulging short-term debt woes in the context of long-term prosperity goals

China’s annual economic target this year of “around 6.5 per cent or higher if possible” is the smallest since 1990, and points to a gradual adjustment of growth expectations and objectives by policymakers following a stubborn slowdown that has lasted seven years. It also underscores a consensus among leaders for the need to give more room to push through some painful reforms to deal with deep-rooted structural problems in the economy.

Since 2010, the Chinese economy has witnessed a steady slowdown, with annual growth rates of 10.5, 9.5, 7.9, 7.8, 7.3, 6.9 and last year’s 6.7 per cent, respectively. Averaged annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates between 1989 and 2009 were around 10 per cent.

In such circumstances, the government has lowered its target to a maximised but achievable level.

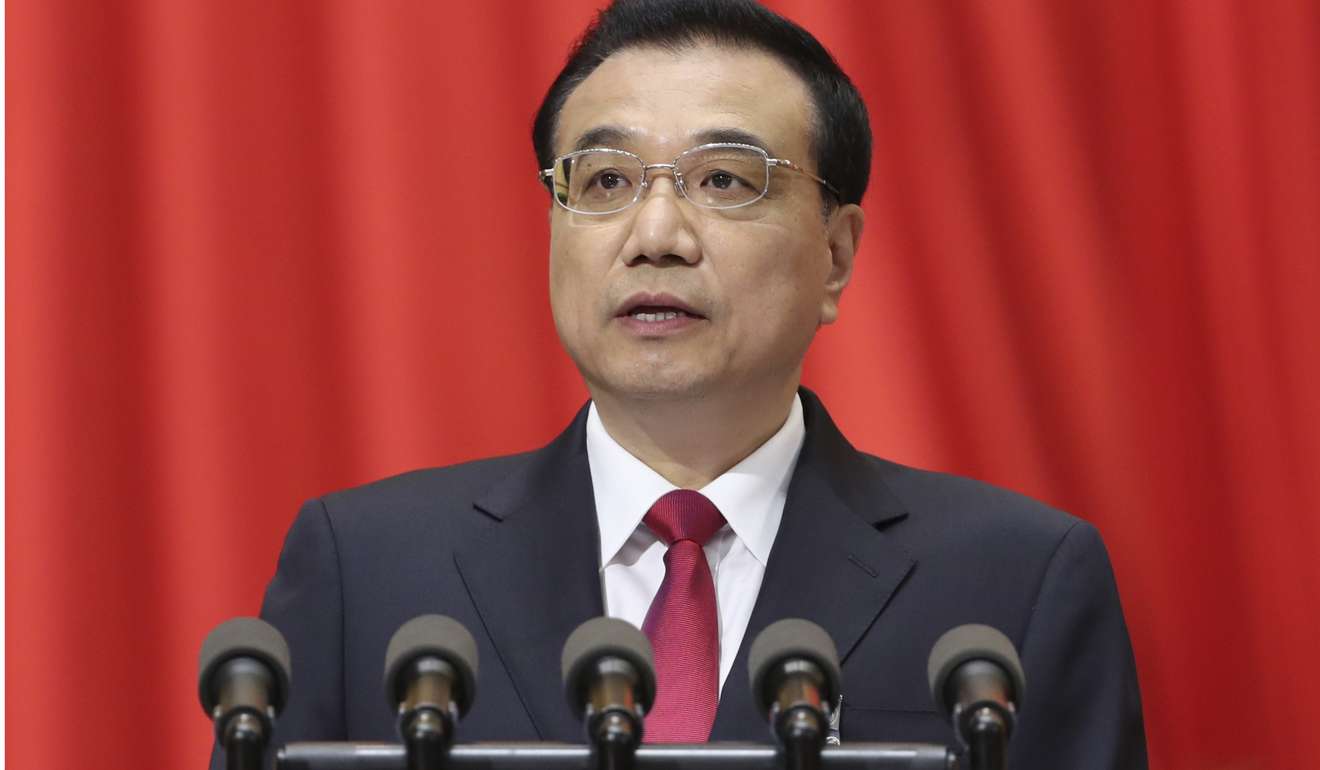

Since his maiden state-of-the-union address in 2013, Premier Li Keqiang (李克強) has lowered the growth rate, from 7.5 per cent in 2013 and 2014, to 7 per cent for 2015, to last year’s around 6.5 to 7 per cent.

The new number, 6.5 per cent, is a minimum target politically. It’s the lowest estimate possible that could still let Beijing realise its goal of doubling per capita income and GDP from 2010 levels by 2020, part of a programme that would allow the Middle Kingdom to measure its society as moderately prosperous.

To achieve this goal, the government used substantial stimulus just to keep the economy powering ahead at even last year’s relatively modest pace. But Beijing’s reliance on repeated infusions of credit to prop up growth since the 2008 global crisis has already driven up debt, which might trigger a banking crisis or drag on the economy.

Surrounded by more uncertainty on the global stage – rising anti-globalisation and protectionist sentiments, the implementation of Brexit and Trumpism and expected rate hikes from the United States Federal Reserve – could put more downward pressure on the yuan and trigger further capital outflows.

Obviously, such external forces would leave the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) with few options, and none of them good. If PBOC chooses to defend the yuan’s value and reduce pressure on the outflow of capital, it has to follow Fed moves to raise rates aggressively. But such action will add further downward pressure on growth.

To achieve the politically charged target, policy support measures, fiscal ones in particular, will probably continue to be expansive, under the name of running “a proactive fiscal policy”.

Although the government set a deficit limit of 3 per cent of GDP this year, the fiscal impulses would seem likely to make that grow in real terms, similar to what was seen last year when the actual deficit was 3.8 per cent of GDP against the targeted 3 per cent.

Such a policy would further push up debt when it is already very high. Total debt owed by local Chinese governments, companies and households has soared from the equivalent of 150 per cent of annual economic output before 2008 to about 260 per cent by the end of last year, the highest among major economies in the world. More than 60 per cent of corporate debts are owed by state-owned enterprises, which crowded out more productive private borrowers.

The S&P Global Ratings, among others, has pointed out that this year’s “economic and financial targets point to a further increase in China’s credit-to-GDP ratio”.

During a high-pressure political season, with a secret party conclave this autumn that could see a major reshuffle of the leadership, maintaining economic stability becomes a top priority. All efforts will be made to avoid major fluctuations as leaders jockey for political advantage.

The most pressing challenge will be maintaining short-term stability while trying to achieve structural reforms that would deliver longer-term economic and financial security. ■

Cary Huang, a senior writer with the South China Morning Post, has been a China affairs columnist since the 1990s