Myanmar has a new insurgency to worry about

The Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army sent a clear signal when it attacked 30 police stations and outposts, just six hours after former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan presented his final report on the Rakhine issue

When fighters of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) attacked 30 police stations and outposts in a well coordinated offensive on August 25 across a wide swathe of territory around the townships of Maungdaw, Buthidaung and Rathedaung, they sent out a clear signal.

For the first time in the history of the Rohingya insurgency, that began in 1946 and has survived many ups and downs, here was a group capable of hitting back when facing a military operation aimed at destroying it.

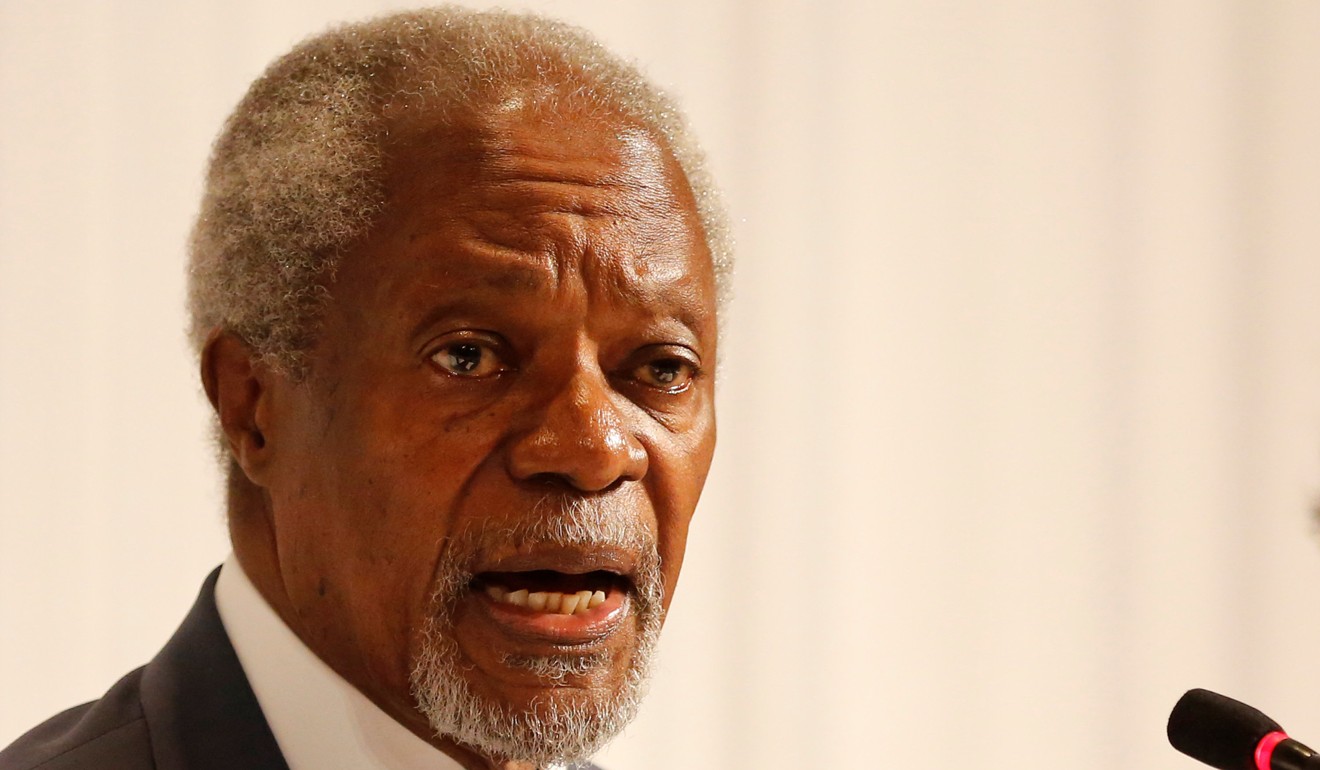

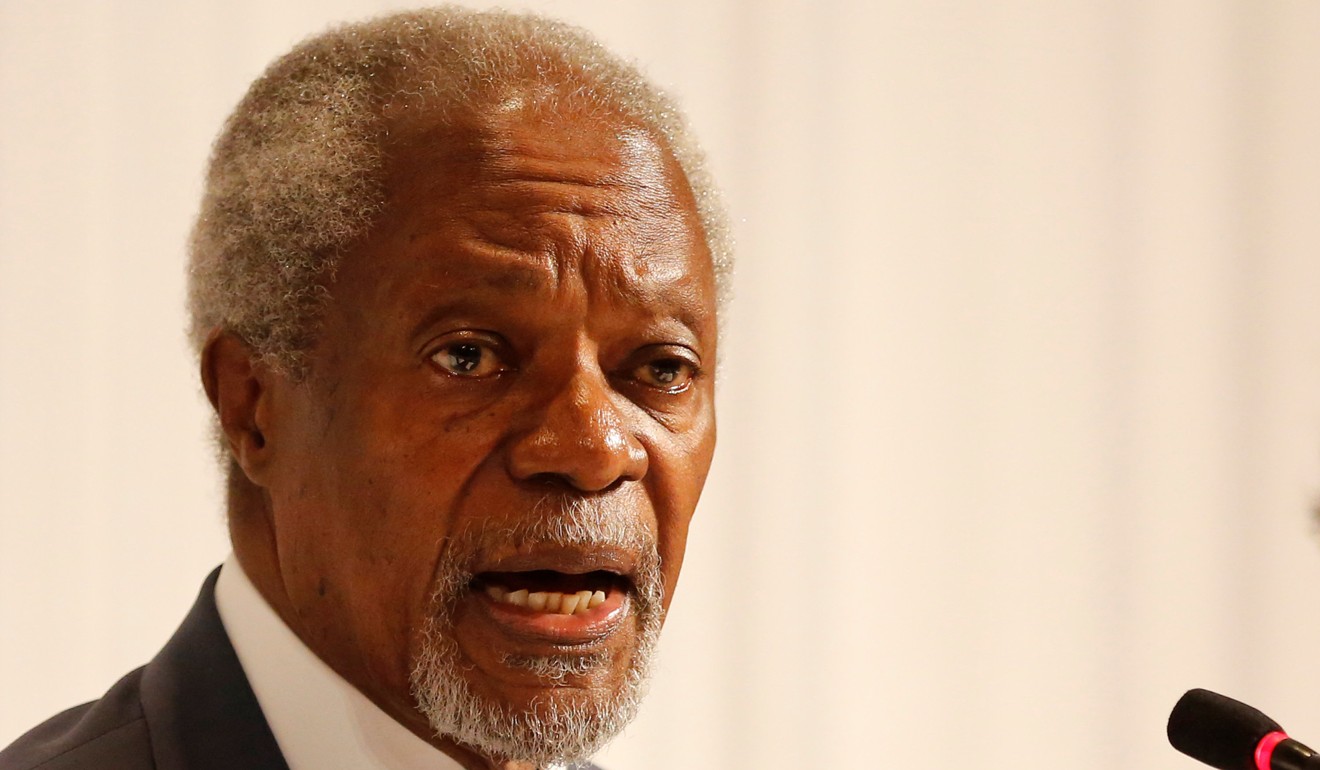

Despite a massive counter-insurgency drive by the 33rd Light Infantry division in the Mayu mountains where the ARSA has its major bases, the rebels were able to mobilise enough numbers in the flatlands of northern Rakhine to stage a well orchestrated attack within six hours of former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan presenting his final report on the Rakhine issue.

Annan has headed the nine-member Advisory Commission for more than a year, with six Burmese and three foreigners on the committee since State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi’s government tasked it with recommending ways to handle the conflict in Rakhine.

On August 24 he presented the final report to President Htin Kyaw and Suu Kyi, listing out a set of recommendations to bring the situation in Rakhine back to normal. Later in the day, he addressed the media, making it clear that militarisation was no answer to the complex situation in Rakhine.

Annan’s report called for extensive inter-ethnic dialogue at all levels and an effort to create human rights awareness in Myanmar’s security forces – and it stressed the need to sort out citizenship issues and related verification issues.

Suu Kyi promised to create an interministerial mechanism to implement the recommendations, but within six hours of Annan’s media conference in a Yangon hotel, the ARSA rebels struck a border police headquarters and 30 other police stations and outposts just after midnight.

Residents of Maungdaw and Buthidaung, speaking to This Week in Asia on condition of anonymity, said scores of armed villagers joined the ARSA fighters in the attacks.

“The rebels fired and mowed down the policemen who were taken by surprise, but it was these armed villagers who stabbed and slashed the policemen with their long knives and machetes,” said a senior Muslim businessman in Maungdaw. For obvious reasons, he was unwilling to identify himself.

Myanmar’s intelligence services estimate the ARSA’s strength at 500 to 600 well-armed guerillas, but the army says at least 1,000 armed men were involved in the attack on August 25.

Like the Maoists in Central India, the ARSA was clearly mixing its armed fighters with a mass of villagers equipped with sharp weapons.

That boosts the number of the attackers, conceals the presence of rebels among them and finally creates a broader base of recruitment for the guerilla group.

The ARSA was successful with its surprise, but seemingly could not follow up on the attack.

By all accounts, they could not overrun their targets or seize huge amounts of weapons – only six firearms were taken, according to a government release.

But they exposed the intelligence failure of the Burmese security machinery and their fighters proved they were not afraid to die.

“That is dangerous. Rohingya have long fought as jihadis in Afghanistan, Chechnya, and in the Middle East. Now that they [are] mobilising under one banner, that of the ARSA, to fight in their own terrain, it is time Myanmar’s security forces wake up and tighten their belts,” said regional security analyst Jaideep Saikia, who has edited a book on Asian terrorism trends.

Is it mere coincidence that the ARSA went on the huge predawn offensive?

The ARSA has said on Twitter that the attack was to break the blockade by security forces of Rohingya dominated areas that forced them into “defensive action”.

The post said that the blockade had reduced towns like Rathidaung and Buthidaung to “near starvation”.

There is no independent corroboration of such allegations – the barring of media by the Myanmar authorities has made it impossible to check on that.

But while there could be some truth in allegations that the Tatmadaw was blocking food supplies, why did the ARSA have to wait to launch the attacks – the biggest since October 2016 – until Kofi Annan had presented his Rakhine commission report to the president and state counsellor and addressed the media conference?

The coincidence is too striking to be overlooked.

The Annan report, made public with its strong conclusions, internationalised the Rakhine State issue.

It was covered across the world as journalists from major global media were present at the press conference at the Sule Shangri-La Hotel in Yangon on Thursday evening. The press, especially in Muslim-predominant countries, covered the event in a big way.

The ARSA had surely planned the strike if what they say is to be believed. If the northern Rakhine ‘blockade’ was the cause behind the offensive, the timing was clearly influenced by the Annan Committee report going public.

They decided to garner greater attention after the Kofi Annan report had brought them some global attention.

Such an extensive attack, carried out in the middle of a military campaign in the Mayu mountains, would have taken time to plan. The mobilisation of so many fighters would not be easy to conceal unless done with great care and deception. So though the planning had been done for a while, a few weeks if not months, the ARSA would have decided to wait for Kofi Annan to make his report public.

Due to a long history of persecution, the Rohingyas are an embittered people, totally alienated from the state that rules them.

The ARSA originated from the Harakah al-Yaqin (Faith Movement) which claimed responsibility for the well coordinated attacks between October 9 and 11 last year, in which nine border policemen and four soldiers were killed. Ataullah, a Rohingya born in Karachi and educated in Saudi Arabia, now heads the rebel group of about 500 to 600 fighters. Hafiz Tohar who raised the Aqa Mul Mujahideen and later merged with Harakah to create the ARSA was trained in Pakistan after he was recruited by Harkat-ul-Jihad of Arakans leader Abdul Qudoos Burmi.

Most of the ARSA fighters have been trained in Pakistan by the dreaded Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (LET) which picked Rohingya recruits from refugee camps in Rakhine after the 2012 riots through its humanitarian wing Fala-e-Insaniyat. The ARSA’s religious guidance comes from a group of Islamic clergy based in Saudi Arabia but its fighting commanders are all trained in Pakistan.

Myanmar’s leading news website Mizzima exposed this link in October last year after the attacks.

The Myanmar government has declared the ARSA a terrorist organisation and asked the media and civil society to refer to them as terrorists and not as insurgents or rebels. It has also asked the media to refer to the Rohingya as illegal Bengali settlers.

So the possibility of the reconciliation that Annan passionately advocated as the way out seems to have vanished.

The government, by insisting that the Rohingya were not indigenous but illegal migrants, looks like closing all doors for reconciliation.

Media reports even suggest the Burmese army had fired at Rohingya villagers fleeing into Bangladesh with mortars and light artillery.

The huge rebel action may have exposed chinks in the Burmese military’s armour, but it has re-militarised the entire discourse on Rakhine.

Despite its obvious failures in anticipating the huge attack, the Tatmadaw (Burmese army) seems to be aiming at a military solution in Rakhine – one resembling the Sri Lankan army’s final military push against the Tamil Tigers.

The ARSA’s links to Jamaatul Mujahideen in Bangladesh and Indian Mujahideen in India – and to its chief tormentor the LET in Pakistan – has upset both Delhi and Dhaka.

India’s Hindu nationalist BJP government has threatened to expel all 40,000 Rohingya in the country. On the eve of a two-day visit to Yangon by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India issued a strong statement condemning the “brutal terrorist attacks” and expressing condolences for the Myanmar security personnel killed.

Bangladesh’s Awami League government, under intense pressure at home to allow Rohingya in for humanitarian reasons, is also wary of the ARSA because of its alleged links with Bangladesh’s top jihadi group, JMB.

“The world must push Myanmar to stop the persecution of Rohingya instead of asking Bangladesh to accept more of them. We are an over populated country with meagre resources,” Bangladesh former foreign minister Dipu Moni had said in a regional conference.

That means the Rohingya, despite having a strong and motivated rebel group, are caught between the devil and the deep sea.

Subir Bhaumik is senior editor at Mizzima Media Group and a former BBC correspondent