Snubbed in world’s biggest war game, will Beijing make waves in South China Sea?

Twenty-six nations are engaging in the massive US-led naval exercise known as RIMPAC. And China isn’t one of them

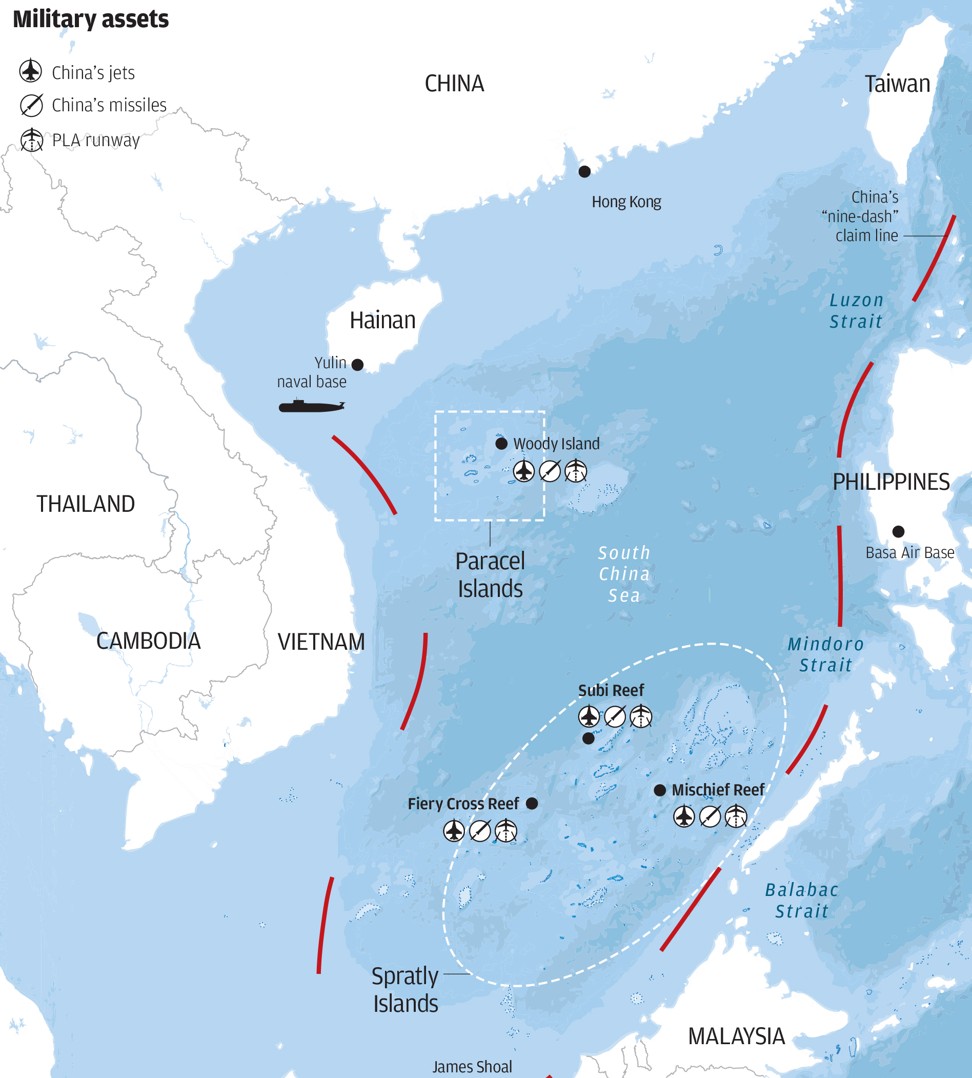

The resource-rich Spratly and Paracel archipelagos may be the main sticking points in the South China Sea territorial dispute – but this week the world’s two major powers were shadowboxing over the issue thousands of kilometres away in Beijing and the Western Pacific.

On the Chinese side, the fresh missive came from President Xi Jinping as he warned the visiting US Secretary of Defence James Mattis that while Beijing – a claimant to the contested waters – was committed to peace, it would not yield “an inch” of ancestral territory.

The Americans’ oblique salvo of sorts coincided with the beginning of the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC), a five-week multilateral naval drill from which the Chinese navy was ejected as a form of protest from Washington against Beijing’s military build-up in the South China Sea.

Billed as the world’s biggest maritime war game, the biennial exercise near Hawaii and the western Pacific Ocean features US navy vessels patrolling alongside warships from 25 countries.

The renewed, albeit low-key sparring between the two major powers comes as no surprise for veteran observers of the decades-old South China Sea dispute, but some say they were alarmed at hardening positions on both sides.

The dispute is over control of waterways and as well as islands in the largely uninhabited Paracels and Spratlys, known in China as the Xisha islands and Nansha Islands, respectively.

Unlike China and competing claimants Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam and Brunei, the US is not a party to the territorial dispute.

But Washington remains a major player in the decades-old contest because of its position that Beijing’s deployment of airbases, radar systems and naval facilities in the strategic waterway pose a threat to freedom of navigation of international shipping.

That stance has seen the US navy ramp up patrols – also known as “freedom of navigation operations”, or FONOPs – through the waters, which are rich in oil and gas reserves as well as fish. China views these American patrols as incendiary.

Beijing claims 80 per cent of waterways under its nine-dash line maritime boundary.

Its air force in May landed bombers on islands in the area, and satellite images show that China may have deployed truck-mounted surface-to-air missiles or anti-ship cruise missiles on Woody island.

“About the only thing both powers can converge on … would be to avoid spinning the tensions out of control beyond the show of muscle by both sides,” said Koh, who is a research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

Koh and Western observers believe the US decision in May to withdraw China’s invitation to RIMPAC could prod Chinese leaders to rethink their position on the South China Sea.

China was invited to the last two editions of the drill and hailed the exchanges as an opportunity for “pragmatic cooperation” with the US navy and other participants.

In 2016, Beijing sent the missile destroyer Xi’an, missile frigate Hengshui, supply ship Gaoyouhu, the submarine rescue vessel Changdao and the hospital ship Peace Ark. This year’s 26 RIMPAC participants include fellow South China Sea claimants Vietnam, Brunei and Malaysia, as well as China’s neighbours Japan and South Korea. Forty-seven surface ships, more than 200 aircraft and 25,000 personnel will participate in the exercises, which are expected to last until August 2.

Eric Sayers, an adjunct fellow at Washington’s Centre for Strategic and International Studies, said revoking Beijing’s invite could be a “minor demonstration” to China that “they cannot disregard the patterns of acceptable behaviour in the maritime domain”.

China, while sticking to its guns on the territorial dispute, has projected a relatively sanguine image following the snub.

Following Mattis’ two-day visit, the state-run China Daily newspaper struck a positive tone and did not mention the RIMPAC disinvite.

“The fact that the two militaries are willing to maintain open and honest dialogue speaks of the resilience and maturity of the two countries’ military-to-military relations, which are critical to the broader Sino-US relationship and to control risks,” the newspaper said in an editorial on Thursday.

Koh, the Singaporean naval researcher, said he was less relaxed because of the sheer intensity of military activity in the contested waters.

“I’m not that sanguine about the prospect of accidental or inadvertent use of force, caused by miscalculations at the tactical and operational level by local commanders, or simply zealots in the ranks who wished to take matters in their own hands,” Koh said.

The Chinese navy’s swift return to RIMPAC in 2020 could be one way to mitigate some of these risks, other observers say, as they emphasised the importance of frontline personnel meeting one another to break down mutual suspicions.

A recent draft US defence policy bill stated that China could be readmitted to the exercise if, among other things, it established a four-year track record of stabilising the situation in the contested waters. ■