Beijing has a maritime militia in the South China Sea. Sound fishy?

- The discovery of a vast ‘dark fishing fleet’ around South China Sea reefs claimed by Beijing prompts speculation it is really a maritime militia

- But there are other explanations that could shed light on this phenomena

It is often touted as one of the world’s most dangerous flashpoints; an arena in which the world’s most powerful militaries are involved in a tense stand-off that has the potential to escalate in terrifying fashion at the drop of a hat.

Yet, if a recent report by the influential American think tank the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) is to be believed, a sizeable and menacing maritime militia fleet has already managed to sail into some of the most hotly contested sites in the South China Sea without being noticed.

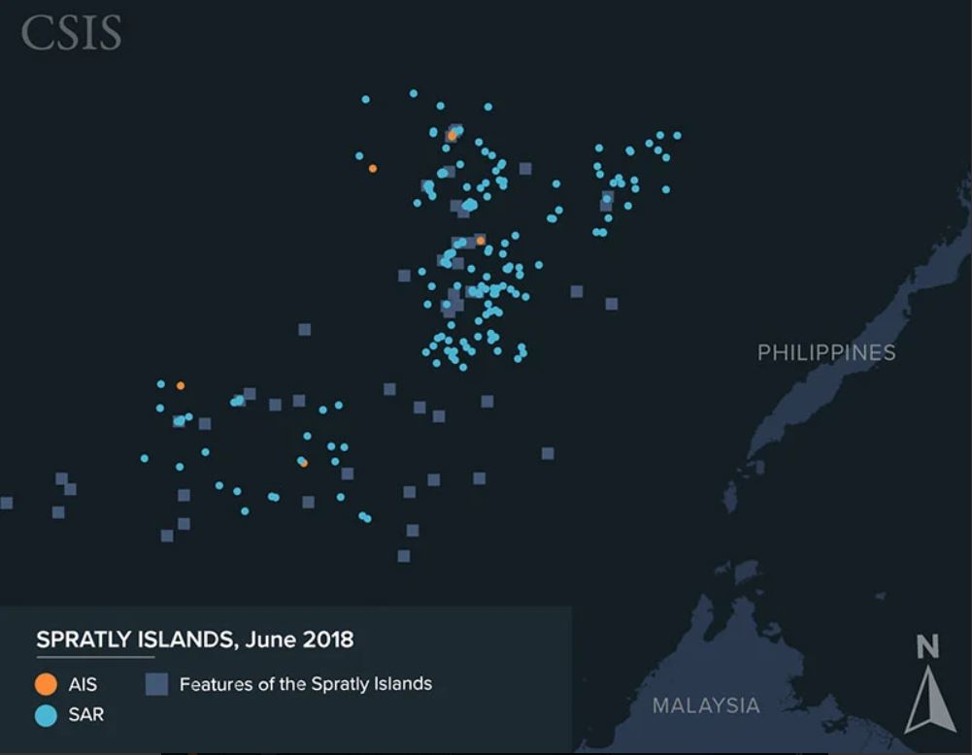

In “Illuminating the South China Sea’s Dark Fishing Fleets”, the CSIS claims to have discovered a “massive presence of [Chinese fishing] vessels in and around China’s outposts … particularly Subi and Mischief Reefs”. It argues this presence is far out of proportion to the area’s known fishing stocks – and notes that many of the vessels hide their presence by refusing to use Automatic Identification Systems (AIS).

Using the latest satellite, radar and infrared imaging techniques, the centre found that in August 2018 (the busiest month) there were about 300 ships anchored at the two reefs at any given time, and that if all of them were fishing they would account for between 50 and 100 per cent of the total estimated catch in the Spratly Islands.

But the CSIS doubts that these vessels were in the area primarily to fish. Despite estimating that 90 per cent of the boats were fishing vessels, it said that “in almost every case the Chinese fishing boats are … riding at anchor or transiting without fishing”.

It gave these vessels a suitably suspicious-sounding label, referring to them as a “dark fishing fleet” and then went on to make a startling claim: that most of them were part of a maritime militia engaged in paramilitary work on behalf of China. (It took up the theme in a subsequent report in February, when it claimed China had deployed dozens of its “maritime militia” vessels to force the Philippines to stop construction work on Pag-asa Island in the Spratlys).

Such claims are not entirely new. Over the past few years, amid growing tensions in the disputed waters, various media outlets and academics have accused China of operating a maritime militia, noting that the growing number of fishing incidents seems to play into China’s strategic and political motives.

Indeed, it would be hard to deny that maritime militias operate in the South China Sea. Each of the key claimant parties in the sea’s territorial disputes – China, Taiwan, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam – to some degree view their fishermen as being on the front line in defending their claims.

And as far as China and Vietnam are concerned, fishing militia have long been an integral part of their security forces. In recent years both Beijing and Hanoi have devoted substantial efforts to expanding their maritime militia fleets in the contested waters.

Nonetheless, using this popular narrative to explain the large “dark fishing fleet” overlooks the complexity of the situation.

Many of the Chinese fishing vessels in this “dark” fleet may simply lack the relevant legal permits. In the late 1990s, to prevent overfishing and control its massive fishing fleet, China introduced a zero/negative growth policy for its marine catch sector. As a result, fishing permits became harder to obtain, and thousands of fishing ships were forced to operate on the black market to survive.

In 2017 alone, Chinese authorities confiscated or banned about 30,000 “black” ships, operating without the necessary licences. Such ships naturally do not install Automatic Identification Systems and even if they do, they usually switch off their transceivers after leaving port. As such, it is not surprising that they would hide their activities in the Spratly Islands.

Also underpinning the CSIS’ suspicions is that the “Chinese fleet in the Spratlys spends far less time fishing and far more time at anchor than is typical of vessels elsewhere”.

But this pattern, while strange, can also be explained by other factors. For example, fishermen from Hainan and parts of Guangdong – and, indeed, from China’s neighbouring countries – have long engaged in reef fishing. Using little more than masks and breathing tubes, fishermen dive into the shallow waters around the reefs to collect high-value catches such as sea cucumbers and top shells.

Since the spectacular rise of Hainan’s giant clam sector in 2012, fishermen from China and elsewhere have taken to illegally harvesting giant clams and sea turtles. Usually, a mother ship anchors in the deeper waters outside the reefs and sends in several smaller boats carrying divers to collect giant clams, turtles and other valuable catches from the shallower waters within the reefs.

Given the Chinese government has been making efforts to clamp down on the giant clam market, ships involved in this trade are unlikely to keep on their AIS.

Another possible explanation is that some of the vessels are involved in transshipments. Some of the larger Chinese vessels could be support boats, which sail to the Spratlys only to purchase catches from Chinese fishermen, barter with foreign fishermen, and provide supplies to other ships, before returning to port.

Informal trading between fishermen in waters around the Spratlys has long been common practice even amid rising tensions. For instance, in May 2014, eleven Chinese fishermen were arrested by the Philippine authorities on suspicion of poaching hundreds of turtles in the disputed Half Moon Shoal. In fact, the turtles had been collected by Filipino fishermen before being sold to the Chinese ones.

Meanwhile, rising production costs and declining stocks have prompted many Chinese fishermen to switch from catching fish to providing logistical support to other vessels, such as collecting catches directly from both domestic and foreign vessels.

For instance, the state-owned Hainan SCS Modern Fishery Group Company (often accused of being a maritime militia) specialises in collecting catches from, and offering logistical support to, fishermen in the offshore waters of the South China Sea.

Finally, those fishing vessels that appear to be transiting the waters without fishing may have been attracted by China’s fishing fuel subsidies.

In 1995, China introduced a special subsidy for fishermen operating in the Spratlys to help cover the cost of long distance sailing. Unlike the general fishing fuel subsidy introduced in 2006, fishermen need to show evidence they have operated in the Spratlys before they can be eligible.

In recent years, declining stocks and overcapacity have made fishing in the South China Sea increasingly uneconomical for many Chinese fishermen.

Consequently, many vessels anchor in or transit through the Spratlys with the sole objective of receiving the special subsidy.

Hence, there are many economic and social factors that explain the large “dark fishing fleet” the CSIS has discovered.

And while it may be wise for claimant states – particularly China and Vietnam – to rethink the role their fishermen play in safeguarding their claims to the South China Sea, it is also imperative not to overplay the narrative that sees all such fishermen as being part of a maritime militia. ■

Zhang Hongzhou is a Research Fellow with the China Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore